Abstract: This study shows which contacts and events were decisive for the publication of essays by John Dewey and William Kilpatrick as a German book in connection with Kilpatrick’s ensuing discussion after 1918 of the project method – in the middle of the Nazi era. The volume was edited in 1935, by Peter Petersen, at the University of Jena, the founder of the Jenaplan (Jena Plan). A number of previously unknown letters, information from various archives and Kilpatrick’s diaries, which are now available in digital form, were used. It was not possible to clarify all the details. However, it is certain that personal contacts and the educational exchange in American-German relations were not completely broken off with the beginning of Nazi rule in Germany in 1933.

Key words: Project method, William H. Kilpatrick, John Dewey, Thomas Alexander, Peter Petersen, Franz Hilker, progressive education

(Simplified Chinese:) 摘要:(Hein Retter:William H. Kilpatrick的项目教学法如何来到德国:1933年前后美、德两国关系背景下的“进步主义教育”):本项研究展示了对John Dewey 和William Kilpatrick的论文集在纳粹德国的出版产生了重大影响的背景和事件。此论文集于1935年由耶拿制度的创始人Peter Petersen在耶拿学院编辑,其内容与1918年后Kilpatrick的项目教学法引发的讨论密切相关。本文使用了大量此前未被发现的信件、多种档案资料以及Kilpatrick本人的日记,目前这些文档均有电子版本可供参阅。虽然许多具体细节已无从查证,但可以确定的是美德两国之间的个人接触和教育交流并未随着1933年纳粹在德国的统治而中止。

关键词:项目教学法,William H. Kilpatrick,John Dewey,Thomas Alexander,Peter Petersen,Franz Hilker,进步主义教育

(Traditional Chinese:) 摘要:(Hein Retter:William H. Kilpatrick的項目教學法如何來到德國:1933年前後美、德兩國關係背景下的“進步主義教育”):本項研究展示了對John Dewey 和William Kilpatrick的論文集在納粹德國的出版產生了重大影響的背景和事件。此論文集於1935年由耶拿制度的創始人Peter Petersen在耶拿學院編輯,其內容與1918年後Kilpatrick的項目教學法引發的討論密切相關。本文使用了大量此前未被發現的信件、多種檔案資料以及Kilpatrick本人的日記,目前這些文檔均有電子版本可供參閱。雖然許多具體細節已無從查證,但可以確定的是美德兩國之間的個人接觸和教育交流並未隨著1933年納粹在德國的統治而中止。

關鍵詞:項目教學法,William H. Kilpatrick,John Dewey,Thomas Alexander,Peter Petersen,Franz Hilker,進步主義教育

Zusammenfassung (Wie William H. Kilpatrcks Projektmethode nach Deutschland kam: Die “Reformpädagogik” auf dem Hintergrund der amerikanisch-deutschen Beziehungen vor und nach 1933): Die vorliegende Studie zeigt, welche Kontakte und Ereignisse entscheidend dafür waren, dass Essays von John Dewey und William Kilpatrick im Zusammenhang mit der seit 1918 von Kilpatrick in den USA neu entfachten Diskussion um die Projektmethode als Buch in Deutschland veröffentlicht werden konnten – mitten in der Nazi-Zeit. Der Band wurde 1935 herausgegeben von Peter Petersen, Universität Jena, dem Begründer des Jenaplans. Dabei konnte eine Reihe von bislang unbekannten Briefen, Informationen aus verschiedenen Archiven benutzt werden. Ausgewertet wurden auch die heute digitalisierten Tagebücher Kilpatricks. Nicht alle Einzelheiten sind geklärt. Doch fest steht, dass – bezogen auf die internationale Reformpädagogik – persönliche Kontakte und die amerikanisch-deutschen Beziehungen mit Beginn der Nazi-Herrschaft in Deutschland, 1933, nicht völlig abgerissen waren.

Schlüsselwörter: Projektmethode, William H. Kilpatrick, John Dewey, Thomas Alexander, Peter Petersen, Franz Hilker, Reformpädagogik (Progressive Education)

Аннотация (Х. Реттер: Метод проектов У. Х. Килпатрика в Германии: реформаторская педагогика (прогрессивное образование) на фоне германо-американских отношений до и после 1933 года): В данной работе показано, какие контакты и события стали определяющими для того, чтобы очерки Дж. Дьюи и У. Килпатрика смогли быть опубликованы в книжном варианте в Германии на фоне вновь инициированной Килпатриком после 1918 года в США дискуссии о методе проектов – и все это в разгар существования нацистского режима. Труды были изданы в 1935 году Петером Петерсоном (Йенский университет), основателем т. н. «Йена-плана». При этом стало возможным включить в издание целый ряд ранее не опубликованных писем, сведения, полученные в ходе работы в различных архивах. Были проанализированы дневники Килпатрика, которые на сегодняшний день уже переведены в цифровой формат. Не все детали еще прояснены, но можно определенно говорить о том, что – с проекцией на интернациональную реформаторскую педагогику – и личные контакты, и германо-американские связи с приходом к власти нацистов в 1933 году не были прерваны полностью.

Ключевые слова: метод проектов, Уильям Х. Килпатрик, Джон Дьюи, Т. Александер, Петер Петерсен, Франц Хилькер, реформаторская педагогика (прогрессивное образование).

1. Goal of the Contribution

Peter Petersen (1984-1952), Professor of Educational Science at the University of Jena after 1923 and founder of the “Jenaplan”, edited a book entitled “Der Projekt-Plan. Grundlegung und Praxis” in 1935. The volume contained relevant essays by John Dewey (1859-1952), the most important educational philosopher in America, and his pupil William H. Kilpatrick (1871-1965), the new founder of the project method. Both university educators enjoyed an international reputation in the 1920s. They were regarded as leading representatives of American educational philosophy in the sense of American Progressivism. Both were convinced democrats – in the sense of that understanding of democracy that largely excluded the fact that non-white citizens were second-class in the white majority society of the USA (Retter, 2018b). Both fought fascism in Europe, especially Hitler’s National Socialism. How did it happen that a book that made Dewey’s and Kilpatrick’s democratic convictions apparent could be published in Germany in the middle of the Nazi era?

The present attempt at reconstruction uses Kilpatrick’s diaries which are accessible today via online services (but are difficult to read) and previously unknown letters from Kilpatrick, to clarify details. Widely-scattered and not yet evaluated texts as well as archives are used to answer the question with a preliminary judgement.

2. Petersen’s First Contact with Kilpatrick, 1928

In a previous essay in the IDE Journal, Retter (2018c, Ch. 4) describes how a German group of 25 interested educators and school experts was received by the Teachers College of Columbia University (TCCU) in New York City at the beginning of April 1918. After the program prepared for them, they were introduced to the American education system in various US states through a stay of several months. The facts of the matter have been known for some time in the monographs on educational history on German-American relations after the First World War (Bittner, 2001, 96f.; Koinzer, 2011, 31f. ). It was the first official contact between representatives of leading educational institutions of the USA and the German Reich after the end of the First World War; until the summer, these relations existed in the sense of an international cultural exchange. The German travel group included three university scholars: the two professors Peter Petersen (Jena) and F.E. Otto Schultze (Königsberg) as well as the private lecturer at the University of Cologne, Friedrich Schneider, who was also professor at the Pedagogical Academy in Bonn.

After the German Reich had become a democratic state, the Weimar Republic, in 1919, the interest of progressive teachers in American pedagogy grew in Germany. The cultural influence of the USA on Germany and Austria was enormous in the 1920s, and not only in the entertainment industry and sport; however, nationalist and communist efforts to separate Germany from the leading country of capitalism also existed on the fringes. The negatively connotated term “Americanization” made the rounds and is not completely extinct even today (Paulus, 2010). But in the second half of the twenties, with the increase in American-German contacts, the positive view prevailed, even a German-American euphoria can be assumed (Rust, 1973, 585f.).

Both in America and in Germany there had been a new interest in pedagogical progressivism since the beginning of the 1920s. In the Weimar Republic there was a backlog demand for the idea of democratic education as advocated by Dewey, which, however, remains underexposed in his book “Democracy and Education” (1916) and only becomes clearer in the publication “The Public and Its Problems” (1927) on the basis of “community”.

The German-American meeting of pedagogues at the TCCU in New York, 1928, was so successful that it was decided to deepen the mutual contacts for the following years through educational study trips: Interested American pedagogues visited Germany in 1929, German pedagogues visited the USA the following year; further study trips followed (Retter, 2018c). What did Hitler’s fascism change from 1933 on? In the field of American-German relations within pedagogy, the question was never seriously researched, but was regarded as settled with a moral statement that prevented rather than favoured research. This contribution shows how quickly moral judgements can be misleading without differentiated analysis of the situation.

The first official contact of German educators was planned in 1928 by the Zentralinstitut für Erziehung und Unterricht (ZEU) in Berlin, the leading institution of teacher training in Prussia and the German Reich. The American side was led by the International Institute at the TCCU, which had issued the invitation; the driving force here was Thomas Alexander, the German expert of the International Institute at Teachers College. The German tour group was led by Franz Hilker. Petersen’s impressions of his trip to the USA, which he wrote to his wife Else in Jena, are contained in Barbara Kluge’s dissertation (1992).

The last sentence of the text excerpt from Petersen’s letter to his wife in Jena reads: “Yesterday began the introductory lectures of first experts, a series of the very best; we are acquiring knowledge of America in buckets of purest water” (Petersen, in Kluge, 1992, 204; English translation H.R.; see excerpt above)

It is known that Kilpatrick entrusted all important events to his diary. This unpublished work comprising many volumes is now available for research in digital form in the Gottesman Library of Teachers College, New York. So what did Kilpatrick think about those introductory lectures of the TCCU lecturers for the German guests? Kilpatrick’s diary (Vol. 24, 1928) contains the following entry regarding the effect of his own lecture.

![Figure 2: Mention of Peter Petersen in Kilpatrick's diary (vol. 24), April 6, 1928 (Source: GL-TCCU [GotLib])](http://www.ide-journal.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/IDE-1-2019-8-Retter-03.jpg)

Figure 2: Mention of Peter Petersen in Kilpatrick’s diary (vol. 24), April 6, 1928 (Source: GL-TCCU [GotLib])

Another entry in Kilpatrick’s diary shows that Petersen was impressed by Kilpatrick:

![Figure 3: Peter Petersen, in Kilpatrick's, diary (vol. 24), April 12, 1928 (Source: GL-TCCU [GotLib])](http://www.ide-journal.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/IDE-1-2019-8-Retter-05.jpeg)

Figure 3: Peter Petersen, in Kilpatrick’s, diary (vol. 24), April 12, 1928 (Source: GL-TCCU [GotLib])

[Relevant text] Walk with Professor Peter Petersen. He is like many liberal school men from abroad, he wishes (in their reaction) far more freedom than we are willing so far to give (Kilpatrick, The Diaries, Vol. 24; April 12, 1928).

Note, Kilpatrick’s remark came at a time when his project method in the USA was subject to initial criticism due to its radical child-centred approach. As Michael Knoll emphasized (2011, 170-179), Dewey expressed his dismay that the switch from teaching to project-oriented work makes the teacher’s actions the disruptive variables of a project that is exclusively driven by the student’s interest (“the project”), even though Dewey did not expose his student by naming him, he perceived it “with horror” (Knoll, ibid, 170) that the project method that Kilpatrick sketched in 1918 in a renewed form was associated by followers with his, Dewey’s, name as the core of democratic-progressive thinking. Knoll, who emphasizes not the common ground but the greatest possible opposition between Dewey and Kilpatrick, shows in unsurpassed fine analysis from year to year how the relationship of US educators to the project method changed in the then current publications of the twenties and thirties – towards a more critical attitude. However, the term “horror” accentuated Dewey’s reaction as being too strongly chosen. Wouldn’t it have been more appropriate to speak of “concern” – instead of “horror”?

We know, there were much more radical school concepts that Dewey himself by no means rated equally positively, although they all referred to him. They failed at an early stage to become the general type of public school in the USA:

(A) The Gary Plan of Dewey’s student William Wirt, whom Dewey had supported in the New York school dispute, failed totally in the late 1920s (Retter, 2019b). This was about much more than a teaching concept, namely the interlocking of the entire school system of a big city, including the municipal facilities for mass schooling with shift changes (see Spain, 1923).

(B) Helen Parkhurst’s Dalton Plan – more radical than the project method in terms of the independence of the student role – had been honoured by an essay by Evelyn Dewey (1922), but by no means corresponded to the educational ideal of her father, John Dewey, as Piet van der Ploog (2013, 65-8) shows:- Dewey understood school as a community and, in consequence, regarded it as a democratic institution, but this was dropped by Parkhurst, who nevertheless referred to Dewey’s book “Democracy and Education”. The term “headmistress of the university school” mentioned in the announcement is not an assignment to Columbia University’s Teachers College, but an imprecise term for the name Parkhurst herself chose for her school: “Children’s University School”, which in New York was called “Dalton School”.

Kilpatrick’s “Diaries” prove that for decades Germany and German reform pedagogy played no role in his interest in reception. They also show that Petersen found much closer personal contact with the school reformer Kilpatrick during his stay at the TCCU than with the (much older) educational philosopher John Dewey. His achievement as founder of the Laboratory School in Chicago remained unforgotten, but that was a quarter of a century before. There is also no indication in Petersen’s records that there had been any personal conversations with Dewey. Although Dewey still gave many lectures on the then current educational theory, his important books from the second half of the 1920s onwards – apart from “Experience and Education” in 1938 – had little to do with pedagogical practice but dealt with a broad spectrum of philosophical and socio-political problems.

On April 10, 1928, Teachers College in New York began its first general conference of American educators on the situation of education in the United States; the participation of the German group at the opening was part of the prepared program.

Kilpatrick later also mentioned Dewey as speaker for the welcoming addresses, but right at the beginning – as our excerpt shows – he put the speeches by: “Peter Petersen of Jena, Professor Albert Feuillerat of the University of Rennes [Feuillerat had accepted a Chair at Columbia University in 1927; see Wikipedia entry; H.R.], and Mr. Rafael Ramirez, Minister of Rural Education of the Republic of Mexico.“Commenting on Petersen’s speech, Kilpatrick said (see extract above): ‟I could hardly hear Petersen well enough to pass judgment on his speech.” Petersen himself wrote to his wife in Jena about this event one day later:

Yesterday, April 10, was a serious day for me: I was the first speaker on the program of the 1st National Americ. Conference of Education – after the first words I relaxed; spoke slowly, clearly, with warmth etc. and was a great success … Dr. Alexander said “very well delivered” and it depends on his judgement. (Kluge, 1992, 204). – [Transl. H.R.]

For Friday, April 13, Kilpatrick noted in his diary: ‟Having Prof. Petersen with me. It goes rather well.” (Kilpatrick, Diaries, Vol. 24; see 04-13-19loll28). Petersen had therefore not gone with the travel group, which, according to Hilker, had left New York on the evening of 12th April. He chose his own itineraries, as he himself gave lectures at some guest locations (Bittner, 2001, 98, fn. 35). Petersen’s letters to his wife in Jena made clear just how impressed he was with the schools in the USA – also after his visit to the famous Francis W. Parker School in Chicago (Kluge, 1992, 211); as is well known, after the death of the school founder, Francis Wayland Parker (1837-1902), Dewey supervised Parker’s school (in addition to the Lab School founded by himself and another school). Throughout his life, Dewey was committed to Parker’s educational principles. After his conflictual resignation from all offices at Chicago University in 1904, Dewey followed a call to Columbia University in New York (see Martin, 2002, 205). – On May 9, 1928, Petersen wrote to his wife in Jena:

I’m going to Chicago to “Fr [Francis] Parker School”, I’m just inside, the director, Miss Cook, who I know from Locarno and who has so locked me and her companions in her heart. But we are also so related in our educational philosophy, our thoughts and practice of school life; love never let me go, showed me everything untiringly until 2 o’clock; fine, wonderful, wonderful – what a real child’s life there! I was just like at home … (Petersen, in Kluge, 1992, 211-212)

After his guest professorship at an academic summer school at George Peabody Teachers College in Nashville/Tennessee in 1928, Petersen returned to New York at the end of September. Kilpatrick’s diary for 09-30-1928, a Sunday, recorded: “Professor Petersen of Jena (Germany) was to dine with us, but prevented by a severe cold” (Kilpatrick, Diaries, Vol. 24; see 09-30-1928).

At the beginning of November 1928 Petersen was again in Jena. He brought with him a wealth of ideas and suggestions for his own school, the Jena University School. When he returned to the University of Jena, problems and anger awaited him above all. During Petersen’s stay in the USA, one of the three teachers and a politically left-wing father had attempted to transform the university school into a socialist, worldly school with no religious instruction; this led to the dismissal of a teacher. The “Petersen School” was known nationwide as a reform school, the enrolment of children far exceeded the spatial possibilities. More rooms were urgently needed, the school was bursting at the seams. There were no permanent posts for teachers who worked as financially insecure temporary staff (assistants). These and other problems were the subject of Petersen’s bitter dispute with the Thuringian Ministry of Education. In this situation Petersen accepted an offer from the government of Chile to start the modernization of the Chilean school system as a visiting professor. From the beginning of May to mid-October 1929, Petersen’s location was Valparaiso de Chile. He was largely cut off from the further expansion of contacts with Teachers College in New York.

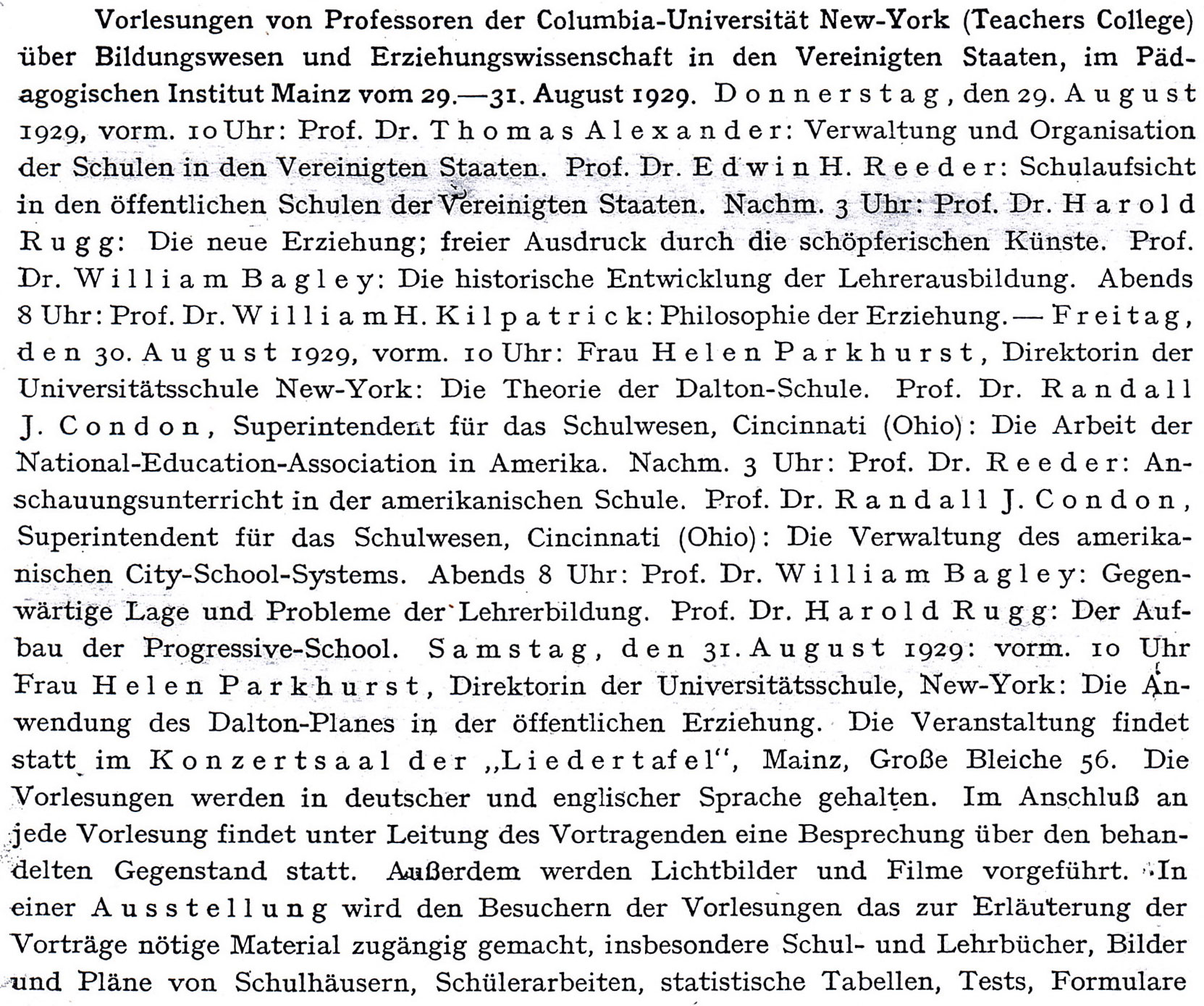

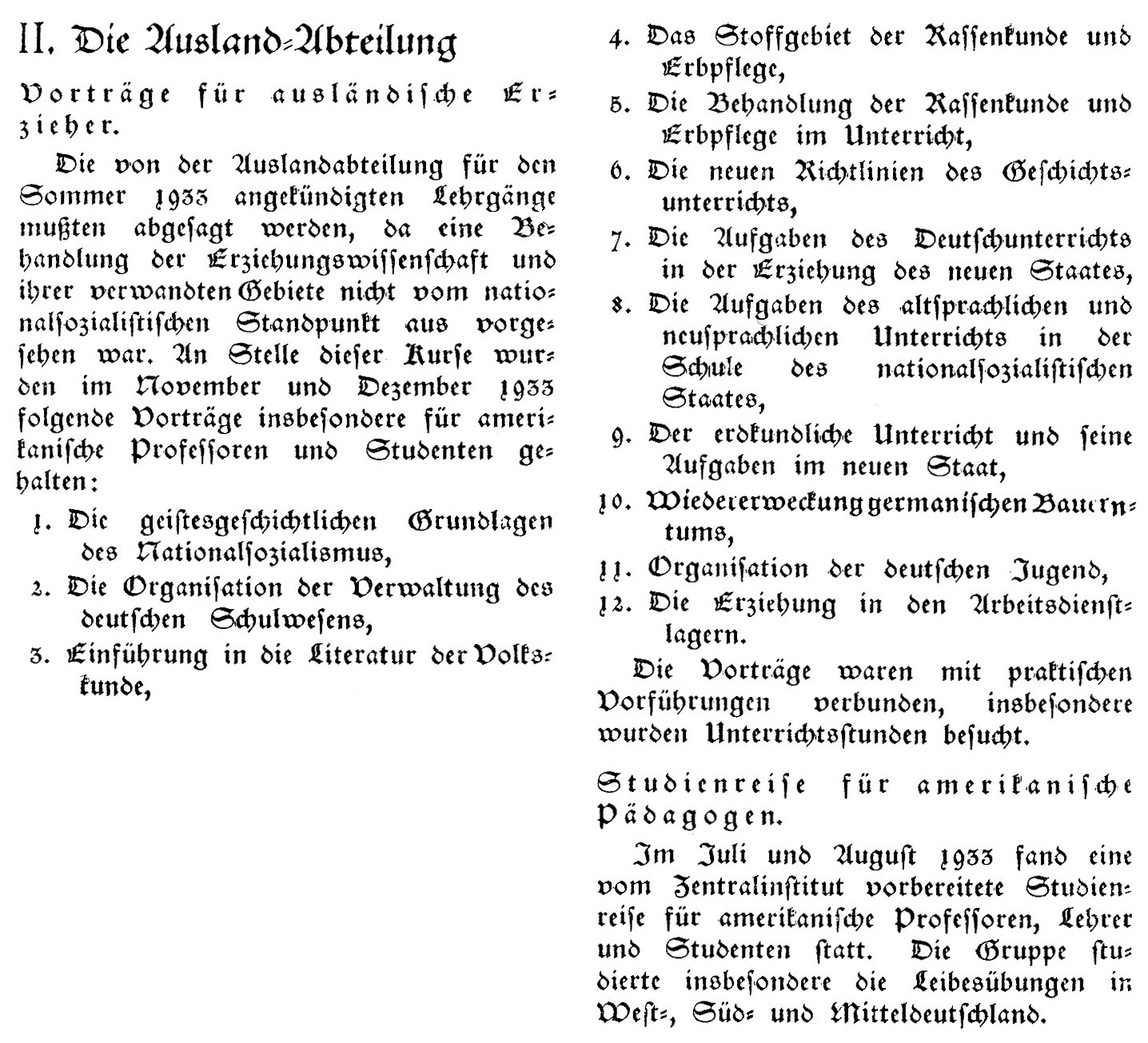

3. Kilpatrick in Germany (1929) – the Contact with Erich Feldmann

The close relations between the TCCU in New York and the ZEU in Berlin that had existed since 1928 led to a three-day event at the end of August 1929 in Mainz, with lectures by TCCU lecturers at the “Pädagogisches Institut [Mainz] bei der Technischen Hochschule Darmstadt” – as Kilpatrick wrote in his diary. The director of the institute was Dr. Erich Feldmann, who was also a “private lecturer of philosophy at the University of Bonn” (wrote Kilpatrick in his diary).

Figure 5: Announcement of the lectures by professors from Teachers College N.Y. and school professionals from the USA at the Pedagogical Institute in Mainz, 1929 (PZ, 1929, 466)

How this arrangement came about is still not clear today. An attempt to reconstruct the facts can be based on the assumption that such an extraordinary event would have taken place in Jena if Petersen had not been abroad. Therefore, it is very likely that: (A) Alexander asked – in coordination with Hilker – Petersen to name a colleague with whose help he would first prepare the project in New York and later organize it on site. (B) Petersen had suggested Erich Feldmann in Mainz. Ever since Petersen had given lectures at Feldmann’s Mainz Institute (Petersen, 1926), he had been in friendly contact with him. This is also evident from Feldmann’s autobiographical review (1975). The Mainz lecture series was announced in the Pädagogisches Zentralblatt (PZ), also in the official publications of the Ministries of Education of the Länder and the teacher associations (see below).

Figure 5: Announcement of the lectures by professors from Teachers College N.Y. and school professionals from the USA at the Pedagogical Institute in Mainz, 1929 (PZ, 1929, 466)As is well known, the project method and the Dalton Plan were the two most important reform concepts originating in the USA and gaining a foothold in Europe – which could not be said for a third US concept, the so-called Gary Plan of the Dewey follower William Wirt (see Retter, 2018b, 100-107). All the more striking is the fact that the project method did not appear at all in the Mainz lecture programme in 1929. Neither Kilpatrick nor any other lecturer offered any information about it. Why? I suppose, following Michael Knoll (2011), it had already been criticized so much in the USA that it didn’t seem attractive enough in Germany to gain a foothold there. In contrast, the founder of the Dalton Plan, Helen Parkhurst, was allowed to talk about the school concept she represented in Mainz on two days. What is also striking is that the topics “Progressive School” and “New Education” were not dealt with by Kilpatrick, but by Harold Rugg in two lectures, while the announced William Bagley, as Kilpatrick’s diary makes clear, did not come (he was in the Soviet Union for six months). Instead, Kilpatrick’s esteemed colleague Robert B. Raupp lectured, in German even. Kilpatrick spoke on his general topic “Philosophy of Education”. The content of his lecture probably corresponded to his lecture translated into German, which he had given to the German guests at the TCCU in April 1928 (Kilpatrick, 1928).

There are two Kilpatrick biographies: on the one hand, Samuel Tenenbaum’s (1951) account of benevolence and reverence, and on the other, John Beineke’s (1998) source-critical monograph written from a historical distance. Both books hardly mention the challenging topic “American Educators in Mainz” at all, “Mainz” is only mentioned in a single sentence. However, the Mainz conference is important for our contribution: it was the starting point for Kilpatrick’s later correspondence with his German colleagues, first with Feldmann, later with Peter Petersen. Therefore, further details of this meeting are given.

The conference in Mainz was not Kilpatrick’s final destination, but the beginning of his journey. Accompanied by his wife, he was on his way to an international meeting of the Institute for Pacific Relations in Kyoto in October 1929, but on a detour via Europe and the Far East. Coming from the USA, Rotterdam was the starting point for further stays after a short stay in England. The itinerary touched Germany, Poland, the Soviet Union (Moscow, Vladivostok), China and other countries.

The first destination in Germany was Hamburg. Here Kilpatrick had a detailed conversation with the university pedagogue Wilhelm Flitner (1889-1990), who had acquired his venia legendi in Jena in 1922; his eldest daughter attended the Jena University School in the school year 1924/25. Flitner was one of the representatives of what was later to become known as a humanities education. He first taught in Kiel at the Pedagogical Academy, but from 1929 at the University of Hamburg. Flitner (1931, 295) promoted international reform pedagogy and its democratic motives. Kilpatrick recorded this encounter:

Had a long talk at dinner and afterwards with Prof. Dr. Wilhelm Flitner of the University, his English leaves much to be desired, but we were able to get on together. We seem to see things much alike. I am quite pleased with him (Kilpatrick, Diaries, Vol. 25, 08-25-1929; source: GL-TCCU).

On August 27, 1929, the Kilpatricks arrived in Mainz – after a detour of their own choosing via Cologne – welcomed by Thomas Alexander, Dr. Feldmann (Director of the Pedagogical Institute), and some American colleagues from the TCCU who lectured in Mainz. On 08-28 a sightseeing tour and a City of Mainz reception, represented by the mayor, followed. The diary entry for August 29, begins with the sentence: “Go to the meeting hall and am much pleased and not a little surprised to see some 1300 (I am told) present” (Kilpatrick, Diary, Vol. 25; August 29, 1929). Feldmann (1975, 200) wrote in his autobiographical review that “twelve hundred teachers” participated in the conference.

Kilpatrick spoke on the evening of the first day of lectures. But he suffered a dizzy spell and left the end of the lecture to his translator, the Berlin American Georg Kartzke (see Kartzke, 1928).

The next day Kilpatrick had recovered. Among the conference participants was the leading socialist school reformer Dr. Fritz Karsen, whose school in Berlin-Neukölln was to bear the name “Karl-Marx-Schule” six months later. They knew each other well through Karsen’s guest role at Teachers College N.Y. during his stay in the USA in 1926 (but Kilpatrick was by no means part of the left wing of Dewey’s followers). As Kilpatrick’s diary gratefully,notes, Karsen was very eager to make the Kilpatricks’ stay in Germany as pleasant as possible, as there was a heatwave at the time.

The next day, the Kilpatricks travelled via Frankfurt am Main to Berlin. Karsen also travelled back to the capital. After initial difficulties Kilpatrick received the visa for the trip through the Soviet Union there. In Berlin he also saw Erich Hylla from the Prussian Ministry of Culture, Franz Hilker (Head of the Foreign Department of ZEU) as well as some participants of the German group who had been guests of the TCCU in New York 15 months previously, at the beginning of April 1928. There is no mention of Kilpatrick visiting any school in the capital Berlin in the diary. The stay was only short.

According to the diary, Kilpatrick discussed philosophical questions of education, some of them controversial, with a number of interested interlocutors whom Hylla had invited. They were concerned at his lecture to the German guests at the TCCU in April 1928, because Kilpatrick refused, following Dewey, to regard a valid catalogue of values as necessary for education. Today one would think of human rights in this context. But education, morality and ethics were pure concepts of experience for Kilpatrick in the spiritual succession of Dewey. This, among other things which Kilpatrick had explained in his lecture at the TCCU at the beginning of April 1928 (here put back into English from the German issue of the lecture in PZ 1928):

Critically tested experience is the final confrontation with all things, [is] experiences, critically tested in their relationships to other experiences. From this point of view, knowledge and “principles” are hypotheses for a guiding experience. […] No principle is absolute, but each can only be applied in the light of all other principles prompted by the situation in question. […] Ethics gets its definition from the desire to bring this good life together for all to the highest possible degree of development. Democracy, much more than a form of government, is the kind of social order that is supposed to promote this good life and the maximum of development (Kilpatrick 1928, 582; see also Retter, 2019).

What did Kilpatrick mean by his ethical demand to give the ‟good life” to ALL citizens in American democracy? Were Afro-Americans, Latinos, Native American Indians included, who were forced by the supremacy of the white majority into social submission? This question will be pursued in the following.

4. Excursus: Kilpatrick, the Project Idea and the Colour Linei

A maxim taken from pragmatism could be this: The deep rift of lacking equality in the social reality of the USA of the twenties, which degraded “coloured humans” to unwelcome individuals of a separately living parallel society, was legally and morally secured by the verdict of the Supreme Court of 1896: “Separate, but equal”. The paradox was that the emphasis on “separate” equality made it impossible to experience equality in dignity. When Kilpatrick replaced ethical principles with critically tested “guiding ideas” of experience, their strength was that they contained and justified precisely what reflected the realities of white superiority. For “should be” and “be” are not distinguished in pragmatism from the outset, a priori; both aspects are (or are based on) experience. According to Dewey and Kilpatrick, a priori settlements were a matter of idealistic philosophy, which was regarded as having been overcome with the new American Philosophy. As history has shown, this did not mean that the idealistic traditions of thought in Europe constituted an obstacle for the mass murders of the dictatorships of the 20th century, especially not for the racial ideology and genocide of the Nazi rule.

John Beineke devoted an entire chapter to the racism problem in his Kilpatrick biography (Beineke, 1998, 353-388). He pointed out that the Southerner Kilpatrick, initially influenced by the racial ideology of his homeland, adopted a more liberal attitude in the course of his life. Beineke stressed that neither Kilpatrick nor Dewey had a vision to change this by actively fighting the existing situation. I think, that was pragmatic, for pragmatism can best regard unresolved problems as the future task of a – supposedly – ever-changing society that has pushed this problem forward without change for a long time.

Kilpatrick’s project idea, in which cooperation between pupils was a matter of course, could undoubtedly be a contribution to the social integration of pupils into American society who had found a new home in the USA, coming from various ethnic groups in Europe and Asia. Was it also propagated for the peaceful and conflict-free coexistence of black and white children in public schools? No, this was not the case and there were reasons for this.

Nevertheless, the project method could have provided good opportunities for children from white and non-white families to engage in joint activities – as social psychologist Elliot Aronson introduced in the early 1970s using the “jigsaw” method to reduce racial prejudice and conflict in the classroom. But such experiments were not Kilpatrick’s intention. Like his revered role model Dewey, Kilpatrick didn’t care so much about America’s historically troublesome legacy. He was in favour of the “new” and the dynamic change of society – buzzwords he both used – but when it came to concrete racism and racial discrimination for African Americans in primary or secondary schools, both were persistently silent, at least in the public debate.

Dewey was a founding member of the first National Negro Conference in New York in 1909, which became the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People, which still exists today. He gave a greeting address in 1909 in which he pointed out that all children should have equal educational opportunities. Unlike Jane Addams, who practised lifelike democracy in the famous Hull House in Chicago and stood up for the rights of African Americans, Dewey did not write a single article in the NAACP official publication. As chairman of the LIPA (League for Independent Political Action) Dewey gave an address to the NAACP Annual Meeting in 1932, but only with the intention of winning voters for the LIPA’s candidate, Norman Thomas, in the 1932 US presidential election. As we now know, this remained completely hopeless. The election was won by Franklin D. Roosevelt.

In Dewey’s book, Schools of To-Morrow, which he published with his daughter Evelyn in 1915, a school reserved for African American children and teachers is portrayed as an example, because the children in the “Black Ghetto” “ of the city of Indianapolis combined school learning with practical work. Such services of black students were useful for the school’s neighbourhood and the whites; the services provided also brought in some money for the black students. Dewey even saw school segregation in this case as an exemplary step to solve the racial problem. Was that Dewey’s idea of the “Great Community”? we may ask ironically today. His ideas of community-democracy did not play a role in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960’s, nor mitigate the violence of white opponents.

At an advanced age Kilpatrick held a number of honorary posts in the decades following his retirement in 1937, but in the Civil Rights Movement of the sixties, which is associated with the name Martin Luther King, he was a spectator at best; Kilpatrick died in 1965 at the age of 93. There is little evidence of how detailed Kilpatrick was interested in the problem of skin colour. Like Dewey he avoided addressing the problem of the colour-line directly and bluntly in all its social consequences. A 1954 Supreme Court decision to separate public schools for black and white children, which was seen as unconstitutional, changed the situation for Kilpatrick.

In the run-up to the Supreme Court judgement Brown v. Board of Education, 1954, there were court proceedings in Clarendon County (South Carolina) to protest against the unequal conditions of education to the detriment of the black children. The racial inequality of the conditions in education regarding black and white public schools was well-known. As was mentioned in the court hearings, the hygiene conditions in schools for black children were disastrous because there was no running water for the toilets. Schools for blacks had hardly any equipment, the care factor (the number of children a teacher had to care for) was much higher than in schools for Whites. Black children often had to walk many kilometres to get to school, while white children had a school bus. Uncovering these conditions in a project led by Kilpatrick would have been democratic action.

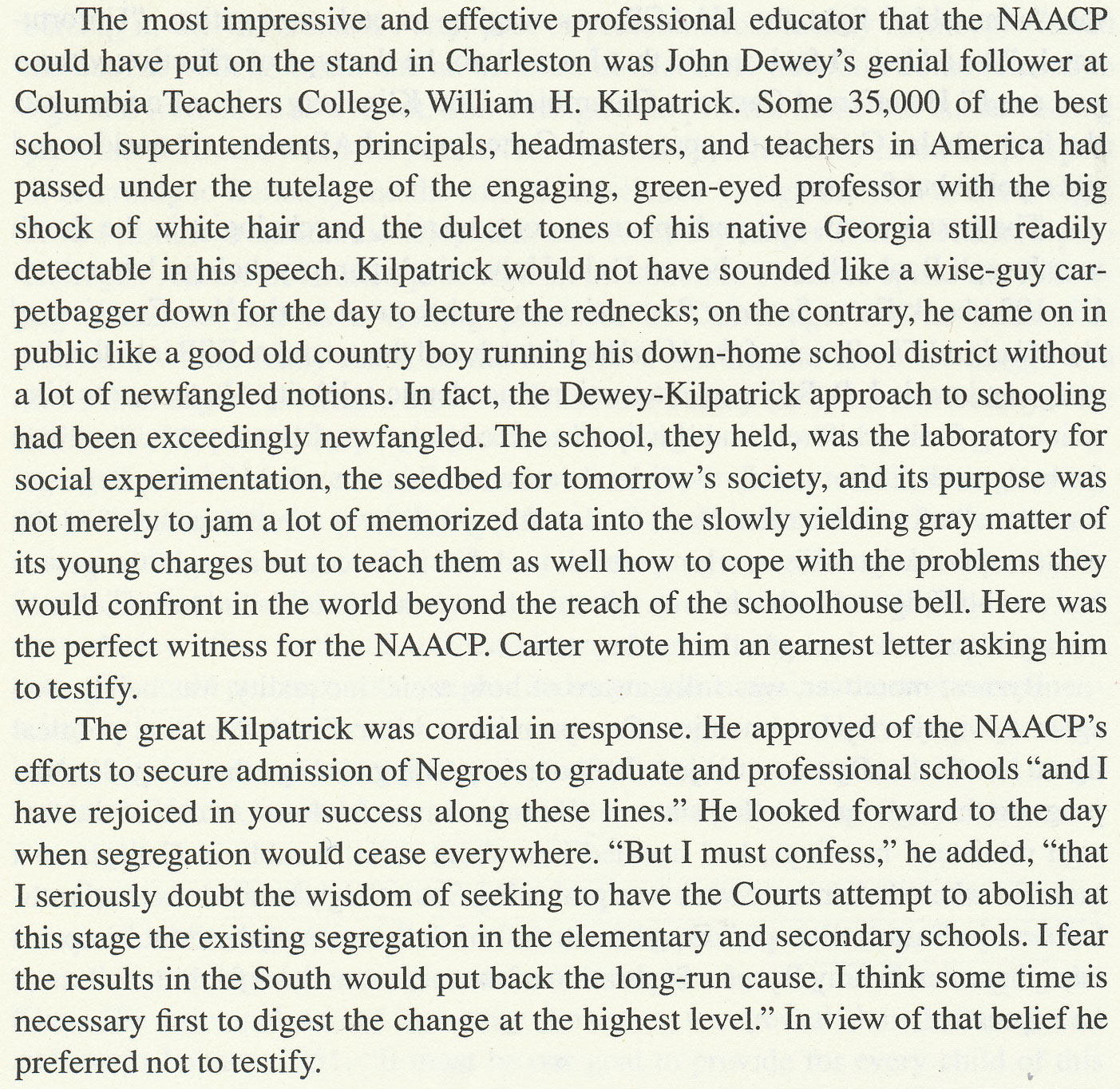

Collings’ Typhus project, which Kilpatrick described as ground-breaking, was considered valuable, not least for social hygiene reasons. Farmers’ families, often threatened by disease, should respect hygiene principles. But the highly acclaimed project undoubtedly concerned white children. To describe this form of indirect racism as democratic was apparently uncommon at the time. For the NAACP it was urgently necessary to get credible witnesses and advocates, who could parry the probing questions of a judge with high expertise and quick-wittedness. There existed very few appropriate black academics. Wanted were professionally impeccable speakers to advocate the fight for equality in education. Richard Kluger’s book about black America’s struggle for equality described the situation and the attitude of Kilpatrick. The following section is informative:

Reading the last sentence again, we see: Kilpatrick refused to stand up for the rights of black children – with the pragmatic argument that this would only make things worse. He was right. After the Supreme Court’s ruling, those families and individuals of the South who had publicly advocated the lifting of segregation in the court proceedings of Brown v. Educational Board were flooded with threats from the local population and assassination attempts followed. Those affected could only flee to cities in the north. But how could Kilpatrick and Dewey, in all conscience, justify praising (American) democracy in the face of this tyranny of violence and injustice?

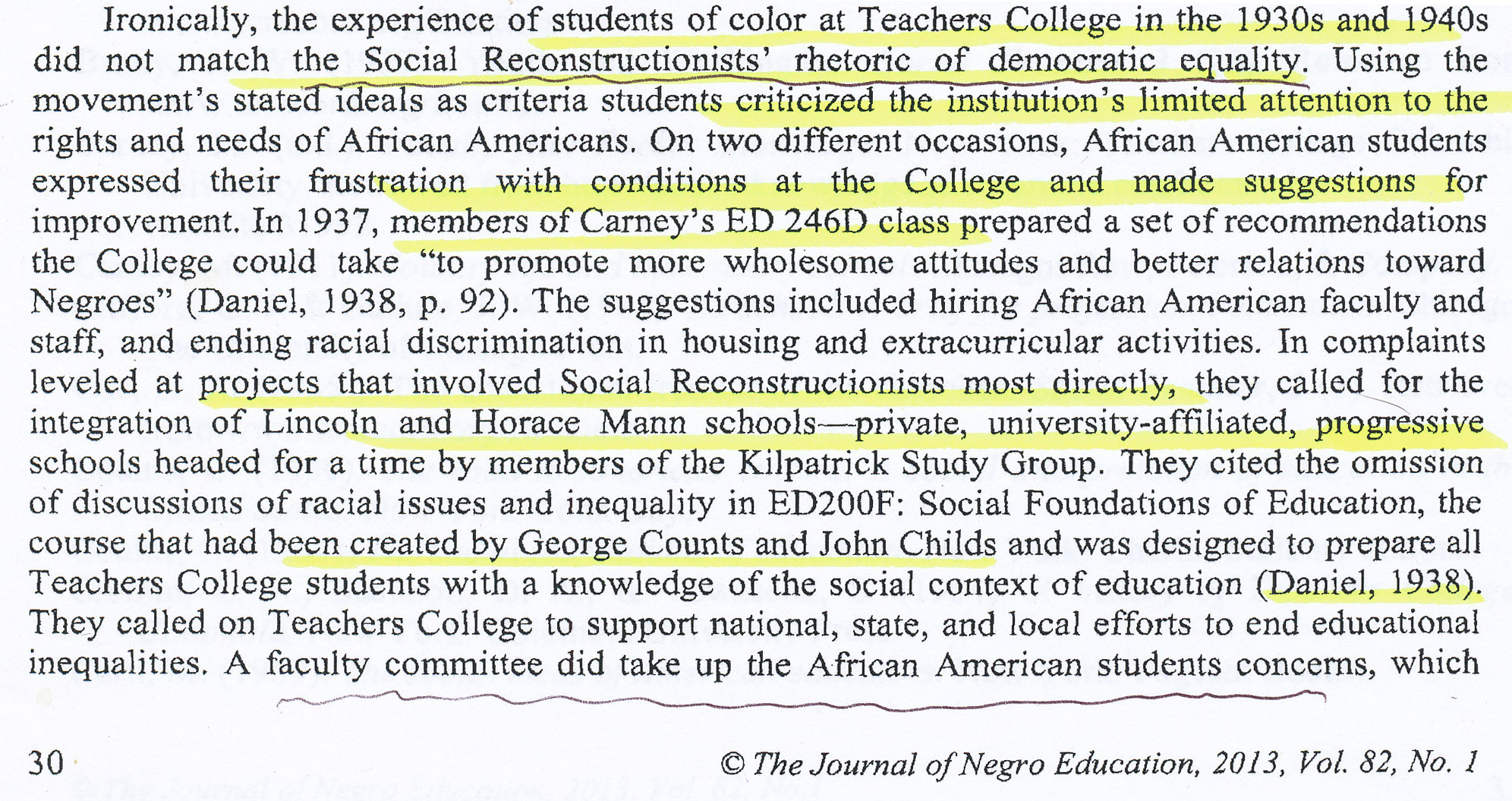

Well, there’s another source for Kilpatrick’s attitude to the racial issue: an article about “Racial Inequality and the Social Reconstructionist at Teachers College” (Columbia University, New York), in 2013, by McCarthy & Murrow. Both authors confirm what was rather shamefully admitted in the opinion of a few American historians: that the interest of the Social Constructivism movement, which Kilpatrick, Dewey and other professors of the Teachers College of Columbia University created, did not or only marginally care about the prevailing racial inequality. But there were a few exceptions, of course, mentioned by the authors. This includes a sentence by the old Kilpatrick dating from 1936, just before his retirement (1937):

We cannot be content with anything less than actual equality of educational opportunity – equal as far as thought and money can reasonably make it so. This means that the rural child shall have equal teaching and equal school equipment with the city child, the Negro child and student with the white child and student, the child in a poor community or state with the child in a rich community or state (Kilpatrick, in McCarthy & Murrow, 2013, 23).

At the time of the Great Depression there were also black students at the Teachers College. Did they feel that they were equally treated? Were they welcome? McCarthy & Murrow say: Not at all!

There were no black professors at Teachers College, black Universities were racially separated. That relatively many Afro-American students were enrolled at Teachers College in New York City, was rather an exception. For instance, at the same time Princeton University had forbidden the enrolment of black students. They were not welcome. Well-known institutions for Afro-Americans were Howard University (Washington D.C.) and Fisk University (Nashville, Tennessee).

During his stay in 1928, Peter Petersen (University of Jena) spent time at George Peabody College, Nashville, accompanied by his colleague Friedrich Schneider (University of Cologne/ Pedagogic Academy, Bonn). Both German professors also visited Fisk University at Nashville in a private enterprise, where only African Americans studied. They were impressed by the friendliness and hospitality there, also by the motivation and high interest for all questions of education there, and they were shocked, coming back to Peabody College about white racism. The Peabody president warned Schneider afterwards:

Wenn Sie vielleicht die Absicht gehabt hätten, hier in den Staaten eine Professur zu erhalten, so ist das jetzt völlig ausgeschlossen. / If you had perhaps intended to have a professorship here in the States, that is now completely out of the question! / (Schneider, 1970, 19).

Petersen wrote to his wife in Jena that his secretary at Peabody College, a German-American woman, had refused to attend Fisk University with him, otherwise she would ‟be cut off socially if she went to see Blacks”. Petersen was also appalled at the way the African Americans were treated in Nashville:

They’ve been almost mean to them here – and now for three days, especially this morning, to intimidate them for Thursday, where the elections for the governor are. One blot among others here (Petersen, in Kluge, 1992, 218).

In Germany at that time the “Negro Question” in the States was not an unknown subject. Every now and then authors informed about the situation within the context of their own attitude. Friedrich Brie (1930), Professor of English and American Studies at the University of Freiburg, wrote an essay of his experiences in the United States of America (As a half-Jew, he was later endangered in the Third Reich, as he supported the resistance; see Brie’s Wikipedia entry). Brie stressed that education had become the key issue for Negroes in their struggle for equality (Brie, 1930, 137; see also Roucek, 1960).

At Columbia University, there was just one (white) lecturer, Mabel Carney, at Teachers College in the thirties who was well-known for her interest in the provision of black education and who gave lectures on the life of Afro-Americans. She retired in 1942. McCarthy & Murrow give an appreciation of Carney in an informative chapter of their article. It took Kilpatrick until 1956 to make his democratic convictions morally credible. In his essay “Modern Educational Theory and the Inherent Inequality of Segregation” he judges openly and self-critically:

How to treat the Negro then became the problem. “Reconstruction” did not solve the problem. Following this, the South undertook what, fairly described, seems to be a definite caste system, with the apparent intent of forcing the Negroes to live permanently as a lower class. To use the Freudian term we can say that two “defense mechanisms” were accepted in support of this caste system: (a) that the Negro race is innately inferior to the Caucasian in intellect and in morality; and (b) that it is ethically right for the superior race to control the inferior. […] Because of this commitment modern education must oppose segregation as the denial of an ideal to which we of this country stand committed (Kilpatrick,1956, 40; 61).

These are not new insights, but they had been clear to every honest and just intellectual for more than half a century. And now, for the first time, the truth of democracy had been clearly expressed by the leading educator of “progressive education”. Dewey, who died in 1952, may have been aware of these words for many decades. But did he say so straight out? At best, he mumbled that racial prejudice wasn’t good. Kilpatrick always suffered from the problem that he was often considered as Dewey’s lackey, hanging on the coattails of America’s most important philosopher. At least at that moment, however, Kilpatrick was Dewey’s moral superior.

5. Petersen’s Interest in Kilpatrick’s Project Idea – a Look at the Contexts

The principles of teaching in Kilpatrick’s project method show an astonishing agreement with Petersen’s ideas, which he brought to life with the Jena Plan. The latter normally has age-heterogeneous learning groups instead of age-homogeneous classes (like modern schools), which had tradition in public schools everywhere in the country, also in the USA. It should already be mentioned here that the method which Petersen called the “group teaching method” formed the basis of the pedagogical “work” of the pupils in the Jena Plan at the Jena University School and was in many respects identical with Kilpatrick’s project idea. However, one difference was that Jenaplan children learnt basic skills and knowledge in the normal mode, as a condition for later project work, and, secondly, there were special courses in maths and also in language where the children were divided up into groups of talents, so that gifted children got a chance to improve their performance. Above all, a large share of school life was determined by the group of pupils themselves. “Helping” the others if they didn’t know or couldn’t do something was socially desired; in traditional school profiles “helping” is punished. Petersen wrote:

Free progress: Once the elementary grammar has been mastered, the child may work freely – always to the extent to which it has acquired the basic knowledge and skills. Then he has free access to all material and all tools, machines, learning aids etc. Since no child is excluded from anything (except because of lack of interest or lack of basic knowledge), and since everyone wants to and can work, the child will turn to the teacher: “Please, introduce me to this field!” We experienced no abuse. A child does not get the idea of playing stupid with tools, machines, if it has learned their seriousness and meaning. It knows that with strong motivation and aptitude it can immediately learn how to use them properly and thus open up sources of real joy, as well as the ability to create valuable and functional things (Petersen 1932, 65, translation H.R.).

The description is fully consistent with Kilpatrick’s child-oriented concept, which in his essay of 1918 stressed that the normal school needed equipment that would enable practical project work. Petersen had such equipment in the university school through the support of the Jena Zeiss Group, which was already internationally well-known for the production of optical precision measuring instruments at that time and still is today. Many Zeiss employees sent their children to the “Petersen School”. But unlike Kilpatrick, Petersen’s teachers had a defined cycle of tasks in the preparation and implementation of pedagogical projects; Petersen spoke of “pedagogical guidance” (Führung) of the group by the teacher but transferred the stimulus-response model of US psychology into the term “situation”. In this sense, teaching is ‘free educational acquisition through natural learning’, whereas the teacher has an observation task in the background and is only active if children need help and in securing learner outcomes.

Challenging stimuli of the given situation usually focus on material or a task prepared by the teacher in order to stimulate the mixed-age (learning-) group of students to react actively. But unlike Kilpatrick, Petersen’s teachers had a defined cycle of tasks in the preparation and implementation of pedagogical projects; Petersen spoke of “pedagogical guidance” of the group by the teacher and transferred the stimulus-response model of US psychology into the term “pedagogical situation”. In this sense, teaching is “free educational acquisition” through natural learning, whereas the teacher has an observation task in the background, active only if children need help and securing at the close the learning outcomes. Children themselves can find stimulating situations which are discussed and edited. But normally the teacher has to prepare such a situation with challenging stimuli. The given situation usually focusses on material, a phenomenon of nature or a striking event. The situation (prepared by the teacher) stimulates the mixed-age (learning-) group of students to react actively. Children of the upper group work in long-term projects, they can choose their subject matter from a given list created responsibly by the teacher, but not without the participation of the students. The chosen topics are complex and can last up to six months. Comprehensive documentation was produced and at the end demonstrated to the public of the school community (see Petersen, 1930).

Now it should be obvious why Petersen had so much interest in Kilpatrick’s project method. He only met him personally in New York in 1928, almost 10 years after the publication of Kilpatrick’s famous essay. As has become clear above, this happened at a time when the discussion in the USA about the “project method” began in some respect to turn increasingly into criticism. In Germany, however, Petersen was interested in the project method, in any case. The reason was simple. His intention was to optimize his Jena Plan theoretically and practically. Thus, concepts of New Education played a role that were useful for integration into the Jena Plan concept. Petersen saw the teamwork of the students in a carefully-prepared, semi-annual project involving group work confirmed in Kilpatrick’s project method. Montessori’s principles of learning supported Petersen’s pedagogy of a stimulating learning environment. It enabled individual learning with materials that allowed self-control. Kerschensteiner’s ‘work school’, the pedagogy of Hermann Lietz’s boarding schools and the method of Ovide Decroly (who integrated the education of normal and disabled children) were important sources for Petersen’s Jena Plan as well.

6. Kilpatrick’s Correspondence with Erich Feldmann and Peter Petersen

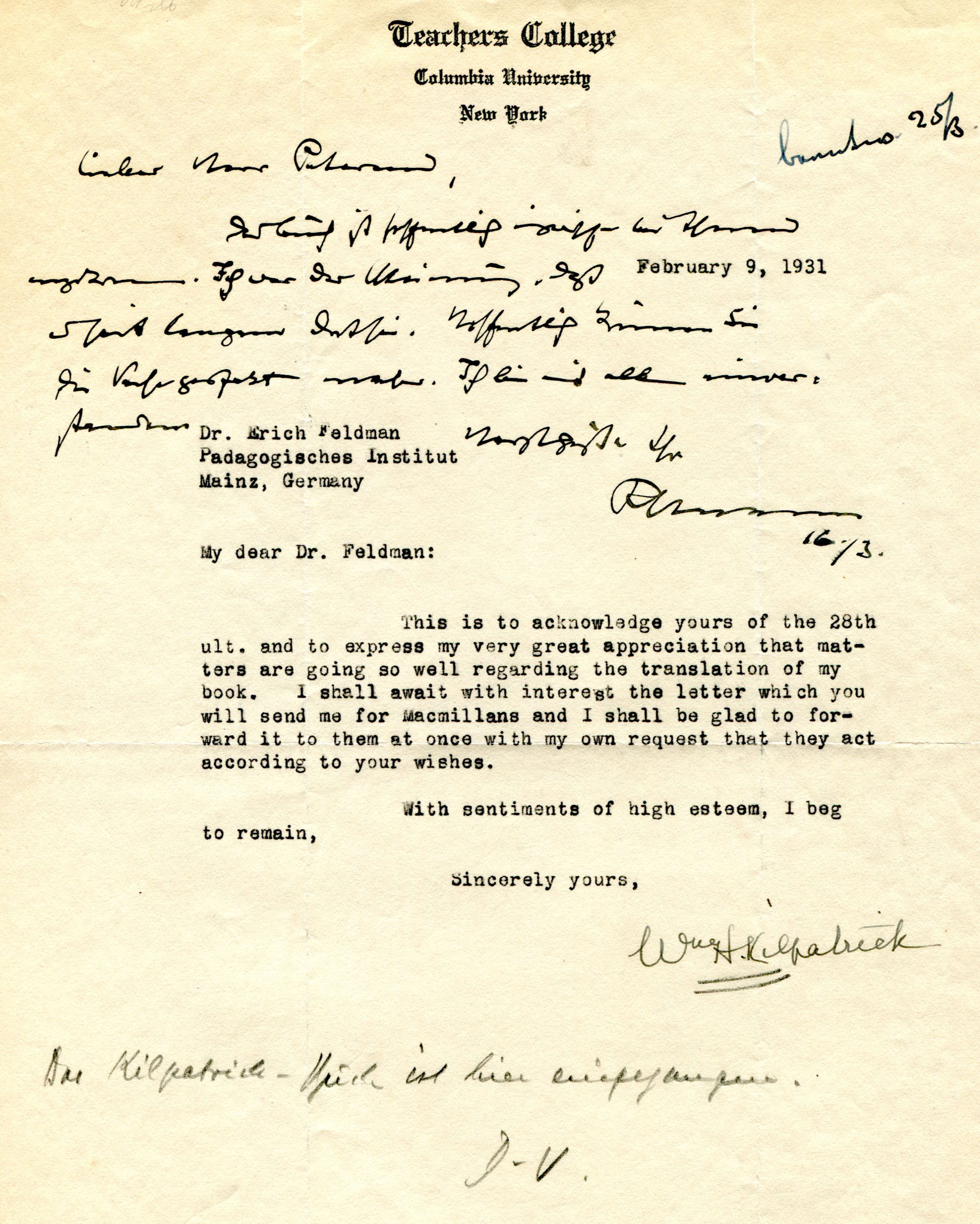

The lectures of the TCCU professors at the Pedagogical Institute in Mainz were a unique event. The communication between Feldmann and the lecturers of Teachers College was apparently not continued, however. But there was a new impetus, the origins of which can be traced back to the meeting of German and American teachers in 1928. I suspect that Petersen was the inspiration for Feldmann’s contact with Kilpatrick. In any case, Kilpatrick answered immediately. The archives have handed down a letter from Kilpatrick to Feldmann in the year 1931. On February 9, 1931, Kilpatrick wrote to Erich Feldmann in Mainz with the letterhead of Teachers College:

My dear Dr. Feldman,

This is to acknowledge yours of the 20. ult. and to express my very great appreciation that matters are going so well regarding the translation of my book. I shall await with interest the letter which you will send me for Macmillans and I shall be glad to forward it to them at once with my own request that they act according to your wishes. With sentiments of high esteem, I beg to remain, sincerely yours, [handwritten] W.H. Kilpatrick

Feldmann’s letter of January 20th, 1931, unknown to us, which, as Kilpatrick mentioned, opened the correspondence, was followed by another letter from Feldmann, which Kilpatrick was still expecting. Feldmann asked him to forward the letter to the publisher (Macmillan) in order to get the copyright for a German edition of the volume “Education for a changing civilization” dating from 1926. This succeeded, because with their letter of 10-18-1933 (received in the PPAV) Macmillan and Kilpatrick communicated the agreement of the publishing house, which in turn forwarded it to Petersen.

The above letter from Kilpatrick to Feldmann dated 02-09-1931 contains a note written in ink by Feldmann, which at the same time proves that he sent this letter to Petersen. The note read: Dear Mr. Petersen, the book has hopefully arrived in your hands in the meantime. I thought it had been there for a long time. Hopefully you can make it perfect. I agree with everything, cordially, your Feldmann, 03-16 [1931] – Another pencil-written entry in the lower part of the letter reads: The Kilpatrick book has arrived here. D-V. It should be remembered that during his stay in the USA Petersen first wanted to win Thomas Alexander for a publication on the Jena Plan educational concept.

The abbreviation D-V is without doubt the abbreviation for “Döpp-Vorwald” – that was the name of Petersen’s assistant at the time. This means that Kilpatrick’s monograph of (1926) to Petersen was available in March 1931 – determined by the intention to have it translated into German and published. Three guest lectures given by Kilpatrick as part of a lecture series at Rutgers University in the US state of New Jersey form the content of the text, which was published as an independent monograph.

Dewey greatly appreciated Kilpatrick’s volume, which Petersen later published in a German translation as the first part of the 1935 anthology. In a letter dated March 2nd, 1928 to Mary M. Maloney, editor of the New York Herald Tribune Sunday Magazine after 1926, Dewey wrote: “I think the best educational books of recent publication are Bode, Modern Educational Theories (Macmillan), Kilpatrick, Education for a Changing Civilization (Macmillan) …” (Dewey 2005, No. 04908).

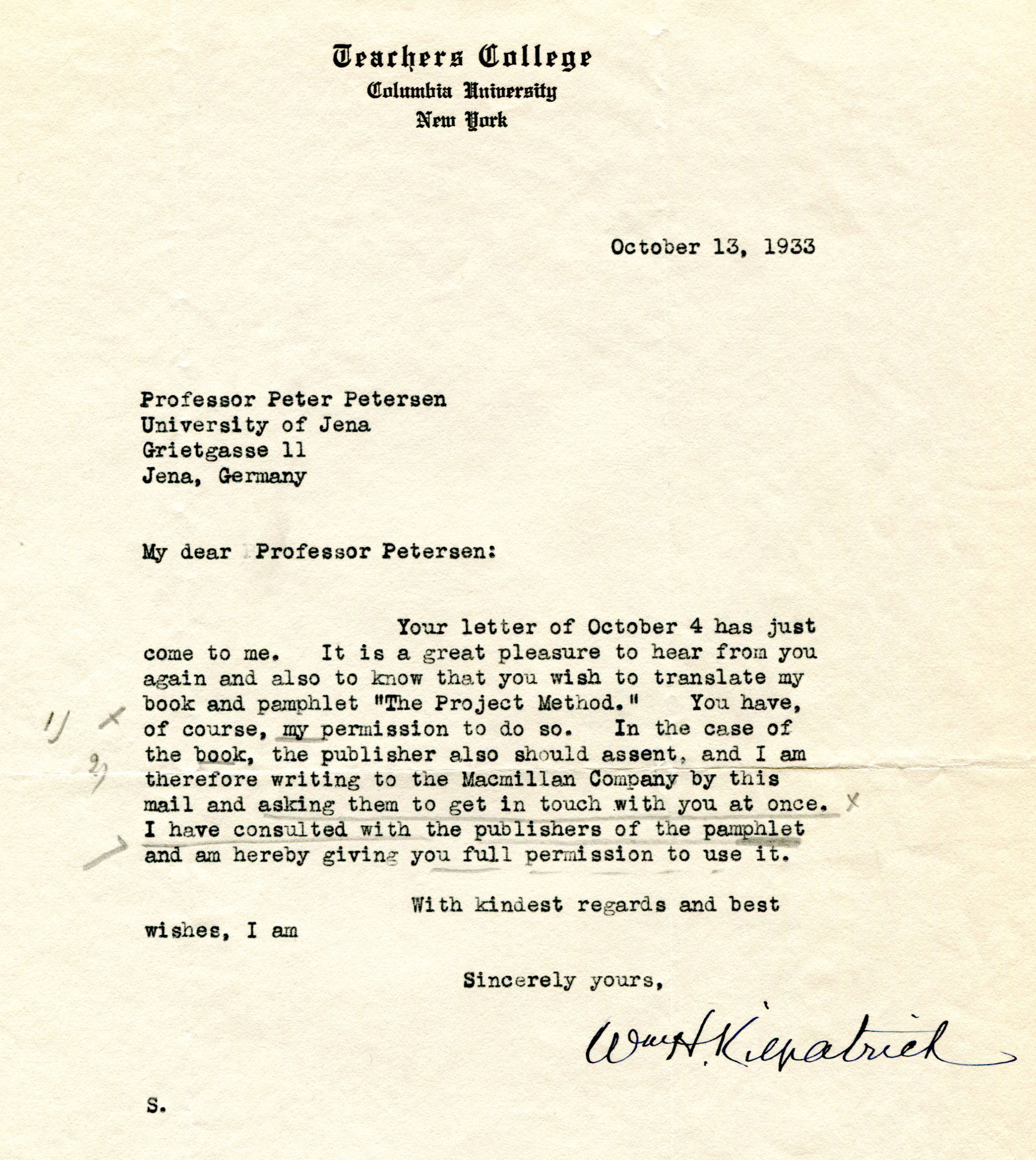

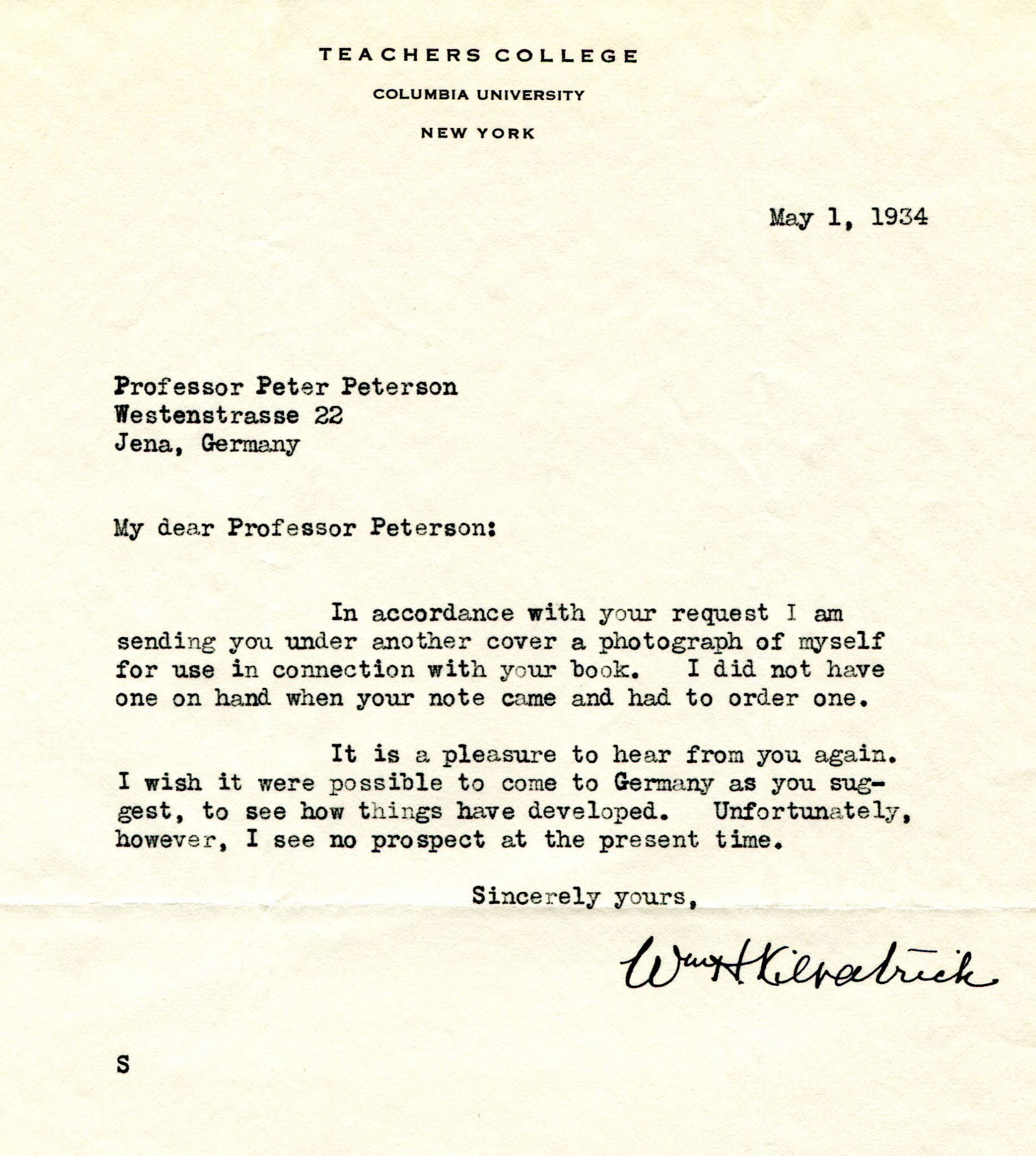

Two more letters from Kilpatrick have been preserved in the Peter-Petersen-Archive in Vechta. Kilpatrick wrote – now to Petersen – on 10-13-1933 and one last time on 05-01-1934. In the first- mentioned letter Kilpatrick replies to Petersen’s – as then not received – inquiry (of 10-04-1933) after the contact to Kilpatrick had become less frequent. The inquiry undoubtedly concerned Kilpatrick’s book and his famous essay on the project method of 1918 to be used for a German text edition. Replying to this, Kilpatrick wrote on 10-13-1933:

My dear Professor Petersen, Your letter of October 4 has just come to me. It is a great pleasure to hear from you again and also to know that you wish to translate my book und pamphlet “The Project Method”. You have, of course, my permission to do so. In the case of the book the publisher also should assent, and I am therefore writing to the Macmillan Company by this mail and asking them to get in touch with you at once. I have consulted with the publishers of the pamphlet and am hereby giving you full permission to use it.

With kindest regards and best wishes I am sincerely yours, [handwritten] Kilpatrick

In another letter dated 10-18-1933 (available in the PPAV) Kilpatrick sent Petersen the consent of the Macmillan publishing house for the German translation of Kilpatrick’s two texts. One last letter to Petersen dates from 1st May 1934:

My dear Professor Petersen,

In accordance with your request I am sending you under another cover a photograph of myself for use in connection with your book. I did not have one on hand when your note came and had to order one.

It is a pleasure to hear from you again. I wish it were possible to come to Germany as you suggest, to see how things have developed. Unfortunately, however, I see no prospect at the present time. Sincerely yours, [handwritten] W.H. Kilpatrick

The last sentences of the letter make clear the distance which Kilpatrick wishes to express to Petersen. The circumstances in the German Reich were not such in Adolf Hitler’s state that he might have wanted to accept an invitation from Petersen.

7. Remarks on Kilpatrick’s and Dewey’s Texts in the Volume “Der Projekt-Plan” (Petersen)

The question is whether the selection of Kilpatrick’s and Dewey’s texts was representative of the two leading progressive educators in the United States, and whether they adequately reflect the state of discussion – not to say the dispute – on progressive education in the United States. My answer to both reflections is ‘yes’, both are true. They are texts of outstanding quality that do justice to Dewey‘s and Kilpatrick’s points of view as well as to the ongoing discussion about “project” and “progressive education” in the USA. In our reconstruction attempt, it remains unclear whether Petersen (without or with the influence of the Central Institute for Education and Teaching in Berlin) selected the texts. It also remains in the dark whether Petersen received suggestions from Kilpatrick and Dewey or from the publishers who owned the copyright.

Kilpatrick’s contributions show a theoretical and a practical focus. The theoretical focus is on the three-part lecture series of the book Petersen had already received about Erich Feldmann from the publisher Macmillan in 1931. The practical focus is on the dissertation by Ellsworth Collings (1923), which was published as a book. Kilpatrick was enthusiastic about the work of his doctoral student Collings. Kilpatrick’s foreword and the so-called Typhus project, which Collings described, make up the practical part of the Petersen volume, “The Project Plan”. Michael Knoll (1996) presented evidence that Collings’ typhoid project never took place but was a mental construction of Collings based on curriculum guidelines. Apparently, Kilpatrick didn’t notice the fake, and the many German teacher educators who informed their students about the Typhus project in the second half of the 20th century didn’t notice it either, because there was no reason not to believe the given text.

While we know a lot about Kilpatrick’s active role in the creation of the book “Der Projekt-Plan” (1935) in Germany, it is completely unknown how John Dewey’s essays got into the volume edited by Petersen. Dewey himself apparently made no contribution to this that could be proven by sources. The Dewey-Correspondence (Dewey, 2005) does not identify the name Peter Petersen – neither by direct letter contact, nor by mentioning the name Petersen in Kilpatrick’s extensive correspondence with Dewey. It is hard to imagine that the US publishers concerned did not notify Dewey of the license request from Germany. Dewey’s then most recent and at the same time most important text, “The Way Out of Educational Confusion”, was a lecture he had given at Harvard University in March 1931. The text was immediately published as a single print by Harvard University Press.

It was the “Inglis Lecture on Secondary Education”, held annually by invited guest speakers. In Petersen’s 1935 anthology, a footnote on the first page of the text informs the reader: “Note: With the kind permission of Harvard University” (Petersen, 1935, 85). The volume edited by Petersen does not contain any further references for the other texts, nor does it contain a name or keyword index, which can certainly be found in Petersen’s introductory works. This is striking for the critical reader of our time and sheds light on the special political situation in Germany in 1935. Letters of the translator Wiesenthal shed light on the special situation (see below). The volume (Petersen, 1935) contains four texts from Dewey’s pen:

DER AUSWEG AUS DEM PÄDAGOGISCHEN WIRRWARR / The Way Out of Educational Confusion / Inglis Lecture Harvard University Press, 1931 [LW 6, 75-89]ii.

DIE QUELLEN EINER WISSENSCHAFT VON DER ERZIEHUNG / The Sources of a Science of Education / First published by Horace Liveright, N. Y., 1929 [LW 5, 3-40]

DAS KIND UND DER LEHRPLAN / The Child and the Curriculum / First published by University of Chicago Press, 1902 [MW 2, 273-279]

DAS PROBLEM DER FREIHEIT IN DEN NEUEN SCHULEN / How much Freedom in New Schools? / First published in The New Republic, 63 (9 July 1930): 204-206, as the final contribution to the symposium “The New Education Ten Years After.” [LW 5, 319-326]

As editor of the volume, Petersen has not separated the arrangement of Kilpatrick’s and Dewey’s contributions, but has jointly subordinated them to a systematic principle – apparently with the intention of moving from general pedagogy and the sociology of education to school and project pedagogy. The starting point is Kilpatrick’s three-part lecture series:

ERZIEHUNG FÜR EINE SICH WANDELNDE KULTUR / Education for a Changing Civilization. The three-part lecture comprises more than one third of the total contributions of both authors and provides an introduction to the social problems of education. Three of Dewey’s four essays follow in the order given above. These three essays are from the years 1929-31, and exactly reflect the debates to which progressive pedagogy in the USA was increasingly exposed in those years. Dewey finds a balance between the principle of the child’s self-activity and the demand for qualified education, according to the requirements of the curricula, which in my view does not deviate from the view he had already given in 1902 in “The Child and the Curriculum” (see the quotation in the following chapter.

In the Inglis lecture of 1931 – for the first time ever in his publications – Dewey explicitly deals with the project method in one section, but without mentioning Kilpatrick. By no means did the project work, which dissolves conventional subjects in favour of holistic contexts of experience, make Dewey a bogeyman: on the one hand, he equated the value of the project method with that of the so-called “problem method” which has its starting point in real factual problems. On the other hand, Dewey emphasized that the contents of the lessons must not be separated from the contexts of life:

The failure is again due, I believe, to segregation of subjects. A pupil can say he has had “a subject”, because the subject has been treated as if it were complete in itself, beginning and terminating within limits fixed in advance. A reorganization of subject-matter which takes account of out-leadings into the wide world of nature and man, of knowledge and of social interests and uses, cannot fail safe in the most callous and intellectually obdurate to awaken some permanent interest and curiosity. Theoretical subjects will become more practical, because more related to the scope of life; practical subjects will become more charged with theory and intelligent insight. Both will be vitally and not just formally unified. I see no other way out of our educational confusion (Dewey, LW 6, 86-87).

8. Dewey – An Opponent of Progressive Education?

In the reception of the project method, John Dewey was often regarded as the actual author and spiritual father of Kilpatrick’s project method, an impression that Petersen also created in Germany through the integrated arrangement of the contributions of both authors in the 1935 volume. After the Second World War, this impression was retained in the German reception of the project method and was only corrected by the works of Knoll (2011). But even in the USA this impression dominated the discussion of the project method following Kilpatrick’s programmatic essay of 1918. Since Kilpatrick constantly referred to Dewey, the latter, founder of the Laboratory School in Chicago in 1896, was also regarded as the spiritual source of Kilpatrick’s project idea.

This was ensured not only by Kilpatrick’s proximity to Dewey’s terminology, but also by Dewey’s texts, which make him appear as the leading figure of the progressive movement. It was not until the late twenties that Dewey himself sought to counter the impression that he was a radical advocate of progressive pedagogy; but by then the term had already acquired a negative connotation in public. As early as 1902, Dewey sought to strike a balance for each chapter in the essay “The Child and the Curriculum”, referring to the significance of the curriculum, which had shown him to be an advocate of a child-oriented and progressive education in his confession “My Pedagogic Creed” (1897) and in his slim, but famous book “The School and Society” (1899). Does he depart from the principle of child-oriented pedagogy? Not at all. Dewey’s summary was:

The case is of Child. It is his present powers which are to assert themselves; his present capacities which are to be exercised; his present attitudes which are to be realized. But save as the teacher knows, knows wisely and thoroughly, the race-experienceiii which is embodied in that thing we call the Curriculum, the teacher knows neither what the present power, capacity, or attitude is, nor yet how it is to be asserted, exercised, and realized (Dewey, MW 2, 291).

For Dewey, the child is foremost. But the task of education requires a curriculum. The quote does not speak of traditional school subjects but refers to the experiences of humanity: life contexts in which courses and subjects certainly play a role, but which are not further emphasized here. This is an attitude fundamentally different from the so-called “essentialists” under the leadership of William Bagley, who emphasized the intrinsic value of the fields of knowledge and regarded the imparting of theoretical knowledge (which usually stands apart from experienced “life”) as a fundamental task of the school. One can only make an opponent of progressive education if one connotes the term negatively from the outset: the self-activity of the children is then declared disorientation, the New Education criticism of the authoritarian role of the teacher interpreted as a lack of respect for the responsibility of the adult in education. But this does not do Dewey justice.

The question remains: To what extent was it justified to regard Dewey’s and Kilpatrick’s ideas of reform as ultimately identical? This was the tenor that shaped the German reception of the Project Plan after the Second World War, as it was essentially only the volume published by Petersen in 1935 that gave this impression. While Kilpatrick repeatedly referred to Dewey, the opposite was not the case; on the other hand, there is no evidence of an alienation between Dewey and Kilpatrick. It seems that Kilpatrick wanted to reform his pedagogical concept in the thirties. Now he described his pedagogical idea as “activity” without responding to the criticism of the project concept, but with new balances regarding the problem of students’ freedom and guidance. And Dewey? At the end of his life, when his own pedagogy seemed to have become history, Dewey adopted a fully supportive attitude towards his pupil in the preface to Tenenbaum’s Kilpatrick biography.

In the second half of the 20th century, the reception of Dewey in the USA in part massively resisted seeing Kilpatrick as an executor of Dewey’s educational philosophy; Kilpatrick was interpreted more as a falsifier of Dewey’s concerns. This can be read in the well-known works of Lawrence A. Cremin, Herbert M. Kliebard and Robert B. Westbrook (see Knoll 2011, 170, passim), which largely followed the intention to emphasize not what they had in common but the opposition between the two reformers, especially with regard to the project idea. The focus of the Kilpatrick debate of American educational historians, however, was not his programmatic essay of 1918 on the project method, but rather what emerged from the implementation of Kilpatrick’s new idea of the “project” in the public schools of the 1920s: a realization of projects instead of lessons, characterized by situational randomness and the subjective needs of the students. The subject principle, fixed essentials, objective goals of the curriculum, which were above the claimed rapid change of society, were abandoned. School should enable real-life experience so that students “actually acquire better and more appropriate behaviours on an ongoing basis”. That is why, in 1926, Kilpatrick made his appeal:

Rid the schools of dead stuff. With those who are in fair touch with educational thought the opinion grows that the present secondary curriculum remains not so much because it is defensible as because we do not have assured material in workable form to put in its place. For most pupils, Latin can and should follow Greek into the discard. Likewise, with most of mathematics for most pupils. Much of present history study should give way to the study of social problems (where more history will be gained than in the old way). […] This new curriculum consists of experience. It uses subject matter, but it does not consist of subject matter. […] It is here again that we wish teacher and pupils to fix their own curriculum (Kilpatrick, orig. 1926: 111, 125, 127; translated in Petersen, 1935, 69, 77f. 79).

What did such absolute freedom of self-determined education mean in the Nazi dictatorship, where the first duty was to follow Adolf Hitler’s commandments and to profess antisemitic racism? The contradiction could not be bigger, but no educational historian was interested in this question until the present day. It is astonishing not only that such ideas of democracy in Hitler’s state could appear on behalf of the ZEU, but also that today’s interpreters are only interested in the editor’s epilogue. Petersen had in fact tried to explain to the readers in his typical way, namely completely implausibly, that the American understanding of “democratization” had nothing to do with the democratic traditions of Europe, but was based on “national community” (Volksgemeinschaft), “in exactly the sense that we give this word today” (Petersen, 1935, 207). The unexpressed message was: the Nazis had to learn from the USA when it came to the “national community”. Hardly anyone of Petersen’s later interpreters dealt with the political dynamite offered by the texts of Kilpatrick and Dewey at the time of the Hitler dictatorship. They demand a democratic education to develop a self-responsible personality in a liberal world.

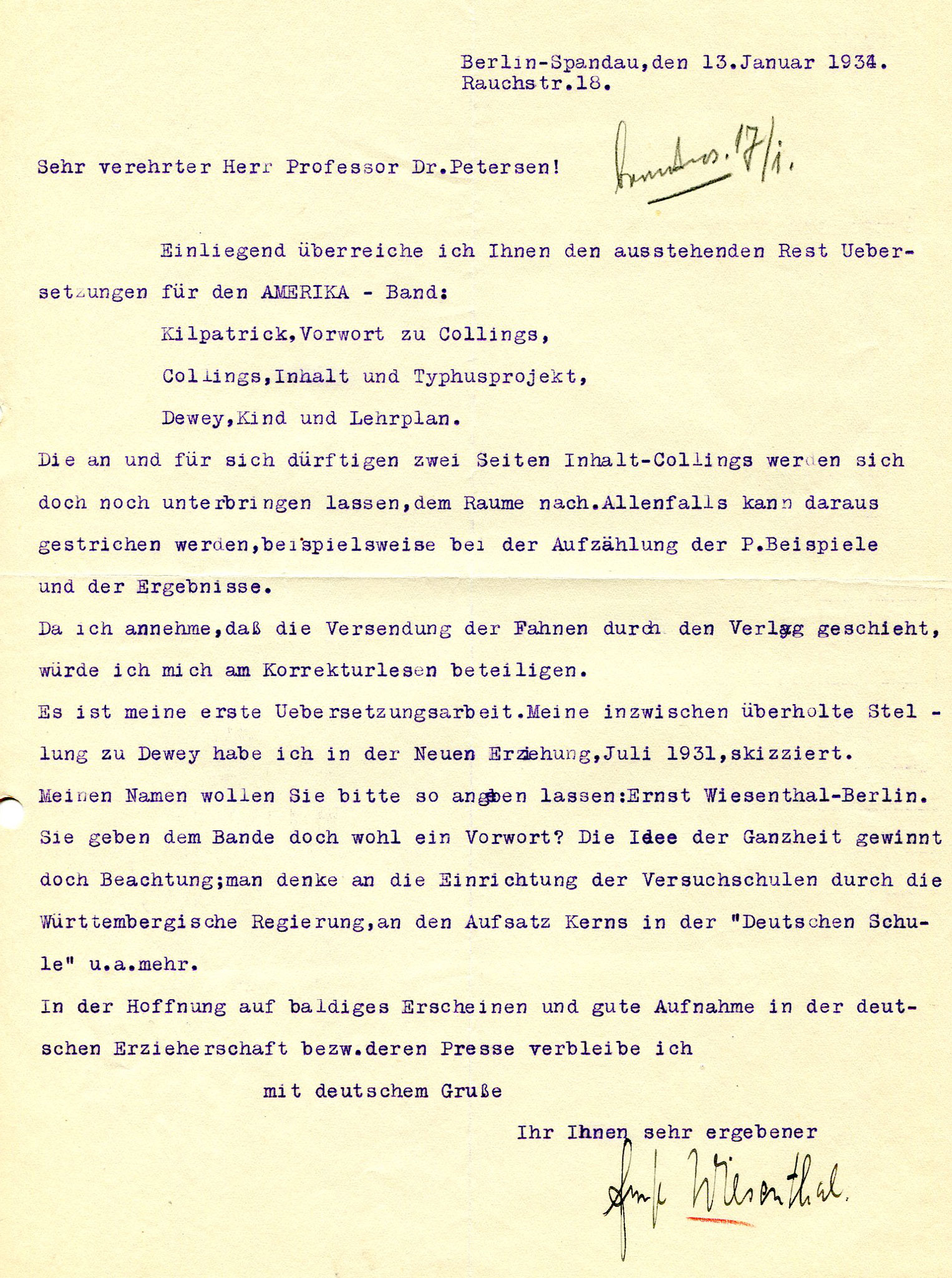

9. The Letters of Translator Ernst Wiesenthal to Peter Petersen – the Political Background

For the planned volume, Dewey’s and Kilpatrick’s texts had to be translated into German. The last page of the book “Der Projekt Plan” mentions two translators: “Georg Schulz, Ettersburg bei Weimar”, who translated Kilpatrick’s EDUCATION IN A CHANGING SOCIETY, and “Herr Ernst Wiesenthal, Berlin-Spandau”, whose work consisted of translating all other texts. Why Georg Schulz did not continue the translation work is unknown. Under certain circumstances he had already carried out this assignment long before 1933, and after a longer break someone else continued with the work, namely Ernst Wiesenthal. I have no proof of the suspicion, but Petersen must have made this decision. It was known of Wiesenthal that he – what a rarity in the Weimar Republic! – had written a high-quality essay about John Dewey – with a remarkable positive evaluation of Dewey’s philosophy. The essay appeared in 1931 in Die Neue Erziehung”, the official magazine of the socialist “Entschiedene Schulreformer” / Determined School Reformers. Bittner (2001, 81f.) rightly stressed that it was apparently “Wiesenthal’s main concern to disseminate Dewey’s writings, which had not yet been covered in Germany”.iv

My archive research at the LAB revealed that Wiesenthal (*1902), who had grown up in Landsberg (province of Brandenburg), was a teacher, living in Berlin from the 1920s, in Berlin-Spandau from December 1933, and later in Falkensee (near Spandau). In 1946, his denazification file contained a detailed curriculum vitae and a list of his newspaper and magazine articles.

Wiesenthal’s file shows that during the Weimar Republic he was politically left-wing, was with the “Young Socialists”, and, in addition to his work as a teacher, developed considerable journalistic activities in teacher newspapers and pedagogically left-wing journals, including “Die Neue Erziehung”. For some time he was also a teacher at the “Karl Marx School” (in Berlin Neukölln, headmaster: Fritz Karsen). Besides, he tried to further his education in English at the University of Berlin and had contacts with personalities in England, where he stayed during the summer holidays. At the beginning of the thirties his educational interest lay in the USA, mentioning left-liberal journals such as “The New Republic” (in which Dewey published). Wiesenthal appreciated John Dewey, whose pedagogy and philosophy Wiesenthal, in his own words, was particularly fond of. He was also interested in Dewey’s “League for Independent Action” (LIPA), the small party of which Dewey was chairman. It is well known that LIPA did not succeed in influencing the electorate in the US presidential elections in 1932, not even African American voters. All in all, Wiesenthal’s knowledge of the contexts of Dewey’s (and Kilpatrick’s) pedagogy made him better suited than anyone else to the task Petersen entrusted him with. There is no indication that Wiesenthal did any damage to the continued practice of the teaching profession, even under the “Law to Restore the Professional Civil Service” of April 7, 1933, on the basis of which the Nazis dismissed left-wing and Jewish civil servants from the civil service. During the war, many big-city families voluntarily sent their children to rural areas of the Reich because of the danger of bombing in the big cities. It was an evacuation measure of the Hitler State, called the Kinderlandverschickung. Wiesenthal worked in a camp for such children in the German-occupied Eastern Carpathians. According to his curriculum vitae, Wiesenthal joined the NSLB in August 1933 and the NSDAP in 1941. He was denazified in 1947 and was then allowed to work as a teacher again.

In his handwritten curriculum vitae, which Wiesenthal wrote for his denazification, which he himself applied for in 1946, he had mentioned the translation of Dewey’s and Kilpatrick’s essays he wrote for Petersen in a single sentence – framed by the following context:

I published an essay about Dewey in the official federal magazine of the Determined School Reformers, “Die Neue Erziehung”. I translated some of his works, which form the larger part of the series “Pädagogik des Auslands” (Education Abroad). When the Nazis came to power in 1933 and further resistance was initially hopeless, I was forced to join the NSLB on August 1st. When the editor [Theodor Wilhelm; H.R.] of the “Internationale Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft” asked me to cooperatev, I refused; I could not justify it before my conscience to inform American authorities and personalities of the appearance of the translation by sending on the documents sent to me (LAB, file Wiesenthal, curriculum vitae, here translated into English).

Wiesenthal’s latter reference makes it clear that from 1933 the Hitler State did not immediately prohibit pedagogical relations with the USA and that the USA, as a non-member of the League of Nations (which Germany under Hitler left in October 1933), adhered to its wait-and-see policy of neutrality. Paul Monroe, professor at the TCCU with high international appeal, was won over by Friedrich Schneider in 1931 as co-editor of the “International Education Review”. Schneider, politically unwanted in the Nazi era, was forced to retire, and the Nazi Alfred Baeumler took over the position as editor-in-chief. Monroe, Kilpatrick’s doctoral supervisor, held this position as co-editor until 1937, or at least his name was used.

Under Nazi rule, the journal continued to publish articles on the USA – now instrumentalized in the Nazi spirit. Although Hitler’s provocations had aroused the distrust of the USA, President Roosevelt’s scope of action in foreign policy was restricted by other constraints (Sirois, 2000, 55). Until 1936, many cultural exchange relations continued, albeit with considerable restrictions and in an atmosphere that could no longer be called free in the German Reich.

It is also significant, however, that, although Wiesenthal mentioned his Dewey translation in his CV in 1946, he did not mention Petersen as editor nor the ZEU as the actual client of the entire series “Pädagogik des Auslands”. Apparently, the ZEU had signalled agreement with the project – but, we have to stress, under new personnel leadership in the Nazi era. Franz Hilker reported after the war how his release from the ZEU took place in 1933 (in Radde, 1995); Fritz Karsen escaped imminent arrest by fleeing (see Karsen, 1993). The Nazi tyranny ended democratic conditions on the legal basis that this tyranny had created for itself. Even if Dewey’s German translation of “Democracy and Education”, was banished and burned, for which Bittner (2001, 107) mentions source documents, a Reich-wide order for burning and annihilation apparently did not exist for this volume, if one looks through the lists of literature published by Wikipedia and described by the Nazis as “undesirable”or “un-German”.

The term “democracy” in the title of Dewey’s volume (translated by Erich Hylla) was decisive for the reluctance it caused among the Nazis. The content of Dewey’s well-known book was not particularly a provocation regarding its democratic theory. In Petersen’s 1935 anthology, on the other hand, Kilpatrick’s thesis that modern industrial society can only do justice to social change on the basis of democracy was a slap in the face for the Nazis. For Kilpatrick stressed, “that in the long run man will not be satisfied with any social order which in principle denies the essence of democracy” (Kilpatrick, in Petersen, 1935, 22).

Petersen, as editor of the text, commented in the 1935 volume on Kilpatrick’s statement (on the meaning of education) that Kilpatrick meant “continuous growth”, and he did this with the recommendation: “See John Dewey, Demokratie und Erziehung. German by Erich Hylla – Breslau 1930. Ch.4: Education as Growth (Petersen, 1935, 83, Fn.)”.

Petersen repeated his positive valuation of Dewey’s “Democracy and Education” (and Kilpatrick’ s project idea) in his book, “Pädagogik der Gegenwart” (1938, l37f., 159-161). – Five letters from translator Ernst Wiesenthal to Petersen survived (PPAV). They were written on 17 April, 23 November and 17 December 1933 and on 13 and 22 January 1934.

Let us consider the accompanying letter with which Wiesenthal sent the last four texts translated by him from English into German to Petersen in Jena, dated January 13, 1934: Wiesenthal mentions that this is his first translation work and offers to participate in the proofreading once the proofs produced by the publisher have arrived. He concludes with the hope that the volume will appear quickly and be well evaluated by German educators.

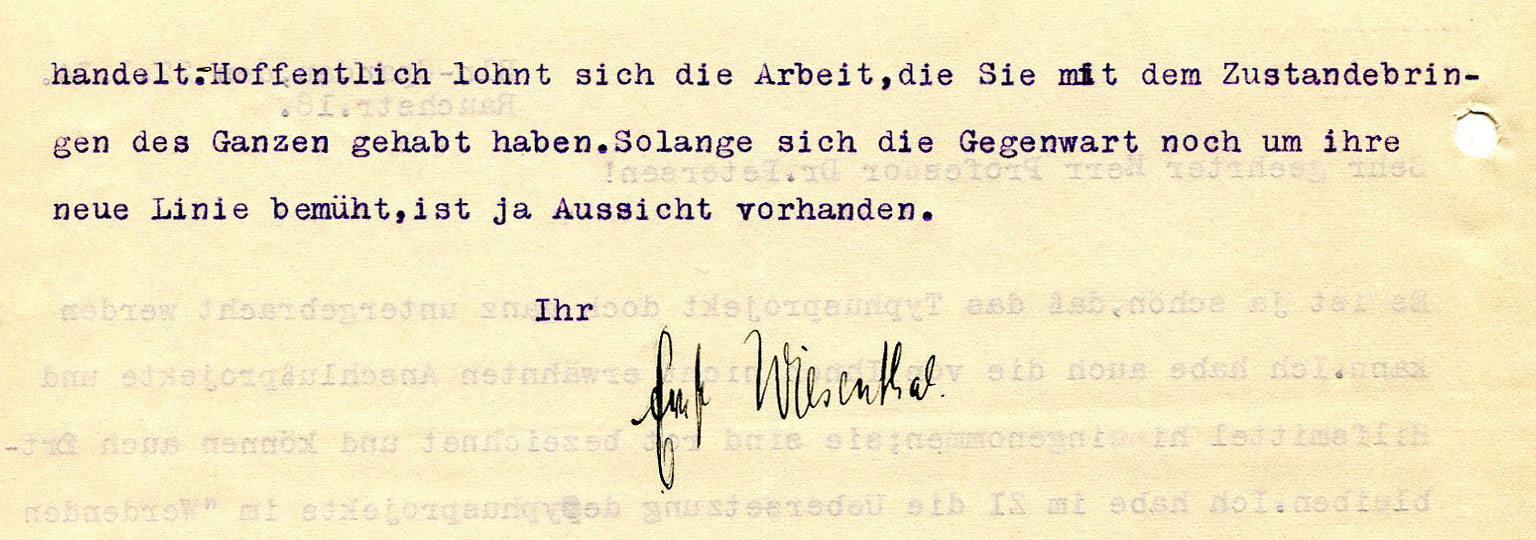

In Wiesenthal’s last letter to Petersen (dated 01-22-1934), which was personally signed and marked the end of the whole enterprise, he signed without the official greeting, but only with “Ihr Ernst Wiesenthal”. It still seemed unlikely to him that texts by Dewey and Kilpatrick could be published under Nazi rule. Wiesenthal’s last words were:

Hopefully the work you had to do to make this happen is worthwhile. As long as the present is striving for its new line, there is hope (Wiesenthal, letter to Peter Petersen, 01-22-1934; PPAV) – see figure 12, below)

10. Petersen, National Socialism and the Jena University School in Jena

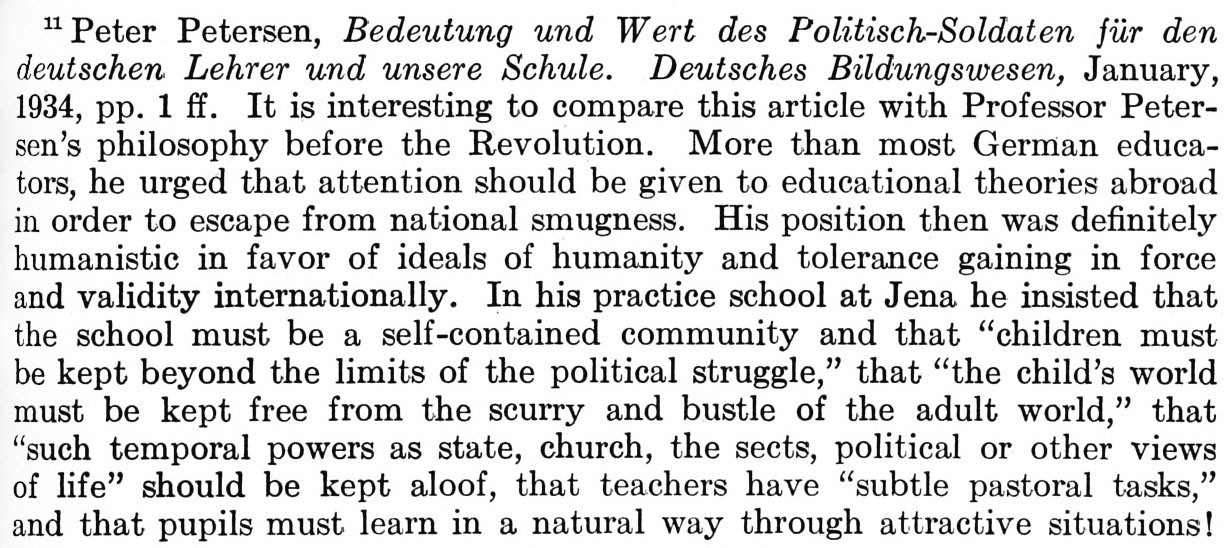

Isaac L. Kandel, as a Jew socialized in Europe, closely followed the situation in the “Third Reich”. At the International Institute, Teachers College, N.Y., he had not failed to notice Petersen’s positive statements on Hitler and on the “national revolution” in the journal of the National Socialist Teachers’ Association (see Petersen, 1934). He mentioned Petersen, in an essay entitled “The Making of Nazis”. Kandel impressed with his excellent knowledge of German journals, books and official regulations. At first it was disturbing to believe that Petersen had become a “Nazi”. In this respect Kandel referred to Petersen’s completely different behaviour before 1933:

More than most German educators, he urged that attention should be given to educational theories abroad in order to escape from national smugness. His position then was definitively humanistic in favour of ideals of humanity and tolerance gaining in force and validity internationally (Kandel, 1934, 465).

However, in his footnote text Kandel showed:

Kandel’s judgment is correct. A few months later the volume edited by Petersen with texts by Dewey and Kilpatrick was released in Germany. This fact, however, has not yet been explained by contemporary historical research. It was ignored because the facts could not be reconciled with the moral judgment on Petersen, which could only be negative – as Kandel made clear.

Today, in the German-speaking world, Petersen is interesting for the history of education researchers of the last 30 years, especially in confirming the moral negative judgment. Only in the context of research that focused on children and parents of the Jena University School did a new research approach emerge. It was known that in the 1920s Petersen admitted a considerable number of children from social democratic and communist families, children from families with Jewish roots and disabled children to the Jena University School. These were from 1933 onwards – considering the NS race laws of 1935 – children who lived together with their parents constantly under the threat of the NS regime to be humiliated, persecuted and killed by the Nazis. What is striking is that Petersen did not expel a child from his school for racial or other ideological reasons, as the exclusionary Nazi idea of a racial “national community” demanded. On the contrary, from 1933 Petersen also admitted children to his school who were humiliated in the public school for political reasons, victims of racial or political persecution (Retter, 2010). New material that has been found awaits further documentation. Therefore, one can assume that the research on Petersen in contemporary history is by no means complete.

11. American Students from New College at TCCU, New York City, in Nazi Germany