Abstract:The article presents a recent study on the question of how young people suffering from psychological risks in their environment recreate social support from teachers in their narratives and what kind of role teachers’ social support plays for children and young adults living at high risk and for strengthening resilience. It points out that teachers can initiate creative metamorphosis of biographical identity to help overcome trajectories of suffering. The link between biographical and resilience research is discussed on the basis of Marica’ si case. One key result is the importance of teachers in the role of significant others, a position which enables them to strengthen resilience. A constructive, trustful and approving teacher-student relationship is the basis for the resilient development of children at high risk.

Keywords: resilience, school, social support, biographical research, case analysis

摘要 (Manuela Diers: 增强在学校中的应变能力- 关于教师如何通过社会支持来提高应变能力的一项叙事研究): 文章提供了一项针对下列问题的最新研究:在他们的环境里遭受心理风险的年轻人是如何在其叙事中恢复对老师的社会支持,以及老师们的社会支持对于那些 生活在高风险中的儿童, 年轻人,并为加强其韧性所起到的作用。作者指出,教师可以发起一项创造性地针对自身传记身份的转变来克服痛苦。在马里卡案例的基础上,讨论了传记研究与弹性研究之间的关系。 一项关键的结果是教师在其他重要角色中的重要性,这一地位使他们能够增强其韧性。一种建设性的,相互信任与欣赏的师生关系是高风险儿童弹性发展的基础。

关键词: 弹性,学校,社会支持,传记研究,案例分析。

摘要 (Manuela Diers: 增強在學校中的應變能力- 關於教師如何通過社會支持來提高應變能力的一項敘事研究): 文章提供了一項針對下列問題的最新研究:在他們的環境裡遭受心理風險的年輕人是如何在其敘事中恢復對老師的社會支持,以及老師們的社會支持對於那些生活在高風險中的兒童, 年輕人,並為加強其韌性所起到的作用。作者指出,教師可以發起一項創造性地針對自身傳記身份的轉變來克服痛苦。在馬里卡案例的基礎上,討論了傳記研究與彈性研究之間的關係。 一項關鍵的結果是教師在其他重要角色中的重要性,這一地位使他們能夠增強其韌性。一種建設性的,相互信任與欣賞的師生關係是高風險兒童彈性發展的基礎。

關鍵詞: 彈性,學校,社會支持,傳記研究,案例分析。

Zusammenfassung (Manuela Diers: Stärkung der Resilienz in der Schule – Eine narrative Untersuchung darüber, wie Lehrerinnen und Lehrer Resilienz durch soziale Unterstützung fördern): Der Artikel stellt eine neuere Studie vor, die sich mit der Frage befasst, wie Jugendliche, die in ihrem Umfeld unter psychologischen Risiken leiden, in ihren Erzählungen die soziale Unterstützung von Lehrern wiederherstellen und welche Rolle die soziale Unterstützung von Lehrern für Kinder und junge Erwachsene, die unter hohem Risiko leben, und für die Stärkung der Widerstandsfähigkeit spielt. Sie weist darauf hin, dass Lehrerinnen und Lehrer eine kreative Metamorphose der biographischen Identität initiieren können, um Leidenswege zu überwinden. Die Verbindung zwischen Biographie- und Resilienzforschung wird anhand des Falles Marica diskutiert. Ein zentrales Ergebnis ist die Bedeutung der Lehrerinnen und Lehrer in der Rolle bedeutender Anderer, eine Position, die es ihnen ermöglicht, die Resilienz zu stärken. Eine konstruktive, vertrauensvolle und anerkennende Lehrer-Schüler-Beziehung ist die Grundlage für die widerstandsfähige Entwicklung von Kindern mit hohem Risiko.

Schlüsselwörter: Resilienz, Schule, soziale Unterstützung, biographische Forschung, Fallanalyse

Резюме (Мануэла Дирс: Развитие резильентности в школе: нарративное исследование о том, как педагоги укрепляют психологическую устойчивость учеников через социальную поддержку): В статье приводятся данные актуального исследования, посвященного вопросу о том, как молодые люди, подверженные в своем окружении психологическим рискам, отражают в нарративах социальную поддержку со стороны педагогов, и какое значение данная социальная поддержка имеет для укрепления жизнестойкости уязвимых групп. Проведенное исследование показывает, что педагоги могут инициировать креативную метаморфозу биографической идентичности, чтобы помочь своим воспитанникам обойти тернистые пути. Взаимосвязь между биографическими исследованиями и исследованиями резильентности обсуждается на примере Marica’si. Главный результат – позиционирование педагогов в роли тех, в ком молодые люди особо нуждаются. Такая позиция позволяет им развивать резильентность. Залогом успешного развития резильентности у детей с высоким уровнем психологической нестабильности являются конструктивные, доверительные и уважительные отношения между ними и педагогом.

Ключевые слова: резильентность, социальная поддержка, биографическое исследование личности, метод анализа случая из практики

1. Introduction

“There are many accounts of children and adults facing and overcoming adversities in their lives in spite of the fact that their circumstances suggested they would be overcome by the adversities” (Grotberg, 1995, p. 10). Marica was still a child when she first experienced violence and adversity. When she was only five, her mother was shot by her stepfather and one year later Marica, her mother and her two siblings fled to an unfamiliar town. While her mother was working, Marica took care of her siblings, cooked the meals, did the housework and had already assumed the role of mother for her younger siblings by the time she was eight or nine. She therefore neglected her schoolwork and had no time to play with friends. Within just a few years Marica changed schools frequently and was fighting against the odds. She had no time to be just a young girl. “Some children seem to escape unscathed, and a few even appear to be strengthened by their adverse experience” (Rutter, 2006, p. 651). And that is how Marica managed her life. After leaving school, she completed an apprenticeship as a dressmaker and additionally worked in the catering business. By the time of the interview she was happily married and living with her husband and daughter in an apartment building.

The above is just a brief description of a resilient biography. Marica suffered from psychological risks in her environment and was living at high risk. She was not alone in her attempts to overcome adverse conditions. Although her mother was not a help – in fact quite the reverse – she found others to support her. Her aunt, her grandmother and the headmaster at her secondary school were the most important people in her life. “Children need to become resilient to overcome the many adversities they face and will face in life: they cannot do it alone. They need adults who know how to promote resilience and are, indeed, becoming more resilient themselves” (Grotberg, 2006, p. 10). The social support of teachers, headmasters or other educators can be a significant resource for promoting resilience in pupils at high risk, as examined in this study.

2. The resilience framework

Resilience is a concept that focuses on the factors in development that promote health and strength. “This topic of individual resilience is one of considerable importance with respect to public policies focused on the prevention of either mental disorders or developmental impairment in young people” (Rutter, 2006, p. 652). A review shows the heterogeneity of resilience research (Diers, 2016; Unger 2018). There is consensus in developmental psychology about two conditions that must be met in order to satisfy the criterion of resilience as defined by Masten and Reed: “resilience generally refers to a class of phenomena characterized by patterns of positive adaptation in the context of significant adversity or risk” (Masten, & Reed, 2002, p. 75). In addition, resilience varies over the course of a lifetime and it must be understood as a capacity which is greatly influenced by context (Rutter, 2006, p. 675; Fingerle, 2011, p. 211). It is necessary to increase the focus on individual developmental processes and context factors which promote resilience.

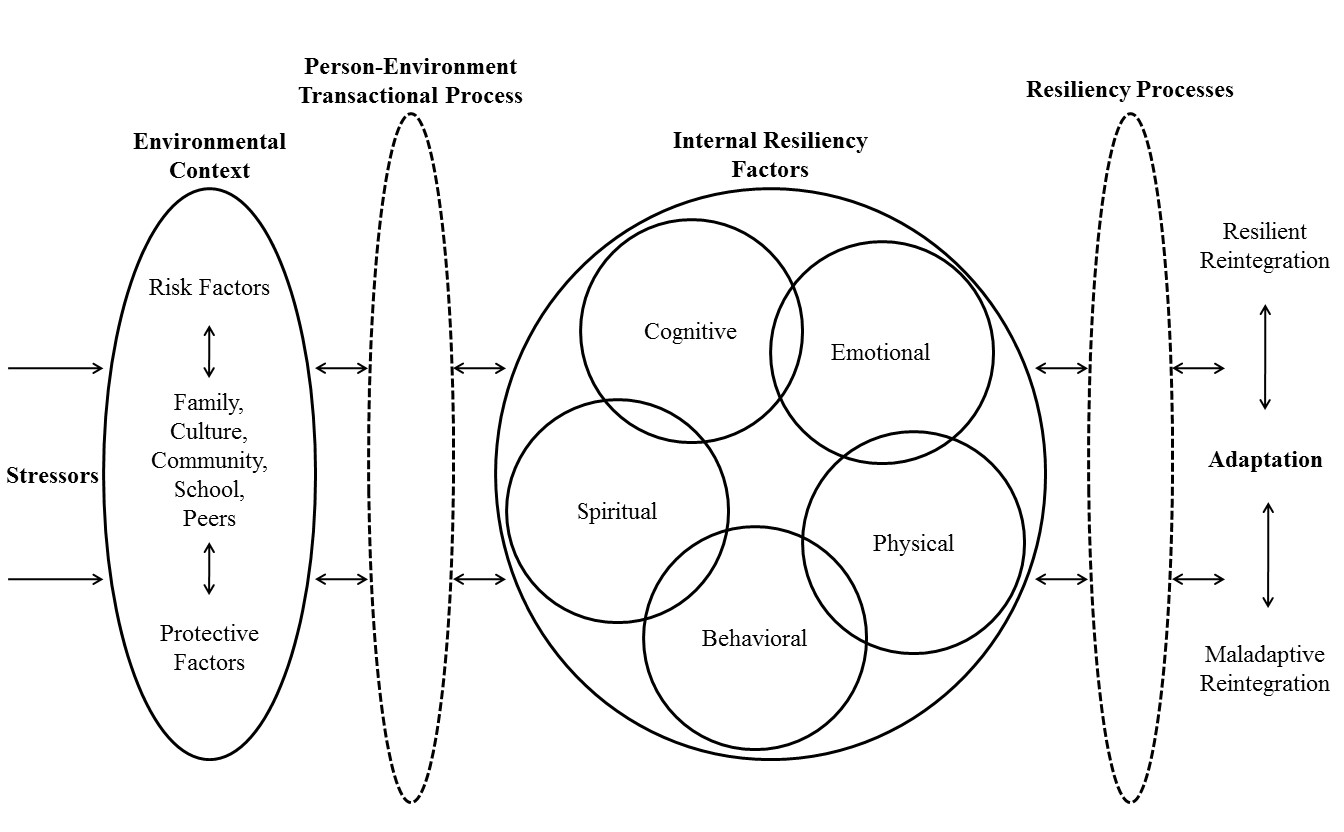

Resilience is not a clearly defined concept, which led Carol Kumpfer to develop the resilience framework to combine the different concepts and definitions. It “should be considered a starting point for organizing factors and processes predictive of positive outcomes in high-risk children” (Kumpfer, 1999, p. 183). Kumpfer emphasises the meaning of the processes which promote resilience. One internal resiliency factor alone does not lead to resilience but transactional processes and different factors in conjunction with one another can strengthen resilience. Her resilience framework includes six main concepts of resilience research.

(1) Stressors: The resilience process is activated by incoming stimuli. The homeostasis in the individual is impaired. This can be perceived as a stressor or as a challenge. According to Kumpfer, the essence of resilience is perceiving the incoming stimulus as a challenge.

(2) Environmental Context: Protective and risk factors in the environment influence the person’s development. They vary according to age and cultural factors. The environment can buffer the negative effects of acute and chronic stress. Furthermore, “most risk and protective factors function as dimensional variables” (Rutter, 2006, p. 652). For example, the divorce of a child’s parents can function either as a risk factor or a protective factor (e.g. if the divorce puts an end to severe conflicts within the family).

(3) The Person-Environment Transactional Process includes the passive or active efforts of the person or caring others to create a healthier environment. “Most of the youth don’t have the option to leave a negative environment or neighbourhood. Resilient youth living in high drug and crime communities seek ways to reduce environmental risk factors by seeking the prosocial elements in their environment” (Kumpfer, 1999, p. 191).

(4) Internal resiliency factors include competencies (cognitive, emotional, physical, behavioural and spiritual) which are necessary to master developmental tasks or other challenges.

(5) Resiliency Processes are transactional processes between the person’s resiliency factors and the development outcome (resilient or maladaptive reintegration).

(6) Kumpfer differentiates between four levels of adaptation (Kumpfer, 1999, p. 211):

- Resilient reintegration, or a higher state of resiliency and strength

- Homeostatic reintegration, or the same state before the stressor

- Maladaptive reintegration, or a lower state of reintegration

- Dysfunctional reintegration or a major reduction in positive reintegration

A positive life outcome must be defined with a view to the cultural context of the individual. Being successful despite the odds means different things to different ethnic groups. The level of adaptation can be measured by mastering developmental tasks. A famous criticism is directed against the normativity of developmental tasks. To defuse this criticism, developmental tasks must be defined within the cultural context. The actional development paradigm (Noack, 1990) gives a framework for the definition of successful coping from the perspective of the individual, the perception of developmental tasks, the individual objective and dealing with these requirements. This requires an analysis of individual developmental processes, which is the aim of this study. The resilience framework provides a structure for analysing individual resilient developmental processes.

3. The concept of social support

There is no common approach to definitions of social support. Definitions are found in three assorted characteristics (Diers, 2016, p. 83): (1) Satisfaction of fundamental needs (e.g. Thoits, 1982, p. 147; Laireiter, 2011, p. 87), (2) promoting of well-being (e.g. Shumaker, & Brownell, 1984 p. 13) and (3) social support as a protective factor (e.g. Nestmann, 2001, p. 1687). In this study, social support is defined as a protective factor in the environmental context which promotes adaptive development despite adverse conditions in that the person protects itself from negative influences or is enable to deal better with negative experiences (Hosser, 2001, p. 34; Nestmann, 2001, p. 1688).

A distinction is made between constructs and contents of social support. Laireiter tried to identify and combine the overall similarities in research on social support. He did not include subconstructs, such as ‘supporting climate environment’, which have no well-founded operationalisation (Laireiter, 2011, p. 88). According to Laireiter (ibid.) social support is understood as a kind of metaconstruct that contains different empirically well-founded subconstructs: social support resources, social support exchanges and perceived social support. Laireiter differentiates between psychological and instrumental social support. The psychological dimension of social support is particularly important in terms of this study and is therefore presented in detail. Psychological support contains supporting actions on an emotional and psychological basis, for example basic emotional support which can facilitate the acceptance of social support or strengthen a sense of belonging. Social support can promote well-being, a sense of acceptance, inclusion, confirmation and appreciation. Self-esteem and self-confidence, optimism and a reduction of fear will be increased in such a way of social integration (Nestmann, & Wehner, 2008, p. 18).

4. Promoting resilience in school

In terms of developmental research, social support can be a strong resource in the lives of children and adolescents who are at high risk (Grotberg, 1995; Werner, 2006; Theis-Scholz, 2007; BZgA, 2009). A confident relationship with a mentor has a positive impact on child development (Du Bois & Silverthorn, 2005; Baker, 2006). Attachment research has proved teachers to be a secure base for children and adolescents at high risk (Pianta, 1992; Grossmann, & Grossmann 2004). This leads to the question of protective factors in school.

In the social environment of adolescents, social support, lasting positive relationships, and adults as positive role models are protective factors which can be influenced by teachers. Teachers can even be significant others for their pupils. Resilience research has produced some hints about promoting resilience in school. Wustmann elaborates promoting resilience by the structure of lessons and also on an interpersonal level (Wustmann, 2004, pp. 134): In education, resilience can be strengthened by encouraging problem-solving ability, strategies for conflict resolution and by assuming responsibility. An appreciative educational style, a trusting internal attitude and social support are factors on the interpersonal level which help to promote resilience.

In the Kauai longitudinal study, the resilient children and adolescents state that teachers are the main attachment figures outside the family. For this group, school is an important refuge point and home (Werner, 2006).

In conclusion, it can be stated that teachers are people with a wide and important influence on children and adolescents at high risk and are potentially the greatest chance for young people who do not have reliable relationships at home. As long as high-risk children and adolescents have reliable relationships in school, they have a good chance of becoming or staying resilient to adversity.

5. Central issue and method

This study focuses on the perspective of young adults on their lives, which has to date played only a minor role. There is no research on the question of how young adults recreate teachers’ social support and the importance of this for their resilient development. The narrative interviews on their lives have been conducted in order to identify the development and relevant processes which promote or hinder resilience. The biographical context can give an inside view on the complex interrelations of resilience processes.

This leads to the question investigated by the study: How do young people who have grown up at high risk recreate the social support received from teachers in their narratives and what role does teachers’ social support play for living at high risk and for strengthening resilience?

Resilient development can be acquired by way of retrospective consideration. Biographical processes are identified from the autobiographical narrative interviews with young adults. Detailed analysis of biographical processes will reveal new insights into promoting resilience processes and interactions in school.

The autobiographical narrative interview is suitable for revealing developmental processes (Küsters, 2009). The survey procedures also include a narrative request about support from outside the family and a questionnaire. The transcripts of the interviews were analysed with the biography analysis (Schütze, 1983; 2005).

The sample contains 22 autobiographical interviews with young people aged between eighteen and thirty. In their childhood they were subjected to adverse conditions and risk factors. They received little or no support from their parents. Varying attributes of the participants were the support of teachers and school, their professional success and overall satisfaction.

The objective of biographical-narrative analysis is to record social reality as it is perceived from the point of view of the interviewed people (Kleemann, Kränke, & Matuschek, 2009, p. 65). In addition, subjective interpretative patterns of the respondents should be revealed relating to the reconstruction of life history (Schütze, 1983, p. 284). According to Fritz Schütze the biographical analysis is divided into different steps. Analysis of the communicative schemes of the transcripts is the first research step to separate the extempore narration from pre-planned and argumentative presentation (Schütze, 2014, p. 229). Secondly, social and biographical processes are worked out in the structural description of the story line. “It attempts to depict the social and biographical processes (including activities of working through, self-explanation and theorizing, as well as of fading out, rationalization, and secondary legitimating of the informant) rendered by the narrative” (Schütze, 2014, p. 230). The third research step is the “analytical abstraction of generalities which are revealed by the text” (Schütze, 2014, p. 229). Analysis of the dominating biographical processes opens up the entire biography is opened with the analysis of the dominating biographical processes. Focussing on the research question reduces the complexity of the analysis results and reveals the main biographical processes that explain the examined social phenomena (in this study the influence of teachers’ social support on resilient development). A focused detailed and contrastive case analysis combines the different research areas (resilience framework and biographical-narrative analysis) in respect of the main research question and concludes the analysis of this study (Diers, 2016).

Schütze differentiates between four biographical processes that are necessary for comprehension of the biographical-narrative analysis (Schütze, 2005). Institutional expectation patterns are biographical actions within the framework of an institution that structures the stage of life (e.g. school, family formation phase) (Kleemann, Krähnke & Matuschek, 2009, p. 69). A person has to comply with prescribed standards to stay there (active attitude of the person). Biographical action schemes are processes to fulfil the person’s biographical aim. The person actively pursues his/her biographical target. In passive and suffering stages of life the person is not able to actively follow biographical action schemes. Schütze calls these phases of life ‘trajectories of suffering’ (Schütze, 1983). In some cases, for example, the person could lose his/her entire legal capacity. Trajectories of suffering end with creative metamorphoses of biographical identity which are induced by the environment and open up new opportunities for biographical action schemes, in this case the person regains his/her legal capacity.

6. Case analysis

Teachers respond to the individual risk position of young people. Teachers can be significant others for children and adolescents at high risk and even create a protective environment in school. This is made quite clear in the case of Marica. In the study three cases were analysed in detail (Diers, 2016) ii. The case analysis of this paper refers only to the case of Marica and is only a part of the overall analysis. By focussing on the strengthening processes in school, this chapter points out how teachers promoted Marica’s resilience by initiating a creative metamorphosis of biographical identity. The social support of her class teacher in secondary school (Mr. Hinrichs) can be described with a quote from Marica: “the person who always tried to get the best out of me”. Mr Hinrichs and the headmaster (Mr. Reiners) were the main contact persons in secondary school. Marica claims that both had a substantial influence on her development: she mentions supporting situations already in the main narration within the autobiographical-narrative interview and explicitly said that they were important contact persons.

After four changes of school, Marica moved into the seventh class. She was suffering from violence and adversity at home and unable to concentrate on her schoolwork, but trying to hide her problems. Mr. Hinrichs realised that her mind was elsewhere and asked her about it. He encouraged Marica to work actively in lessons even though she was tired. Mr. Hinrichs reflected upon everyday things in school and encouraged her. In other words, he took her individual risk situation into account. The teachers’ actions range between the concepts of fairness and performance (Bohnsack, 2009, pp. 40). Probably, the teacher recognizes an impending trajectory of suffering in the form of school failure and tries to counteract.

It took approximately one year before Marica was willing to accept support and confide in Mr. Hinrichs and Mr. Reiners. Because of an impending deportation, Mr. Reiners helped her maintain her place of residence and wrote a successful letter to the competent authority for Marica to stay in Germany. Marica has a migrant background. Her mother was born in Bosnia and her father is a Kurd from Turkey. Marica’s stepfather is a Roma born in Yugoslavia. Marica was born in Germany. Her migrant background was not a special issue in the interview. This degree of support is unusual for supporting actions of teachers, but has to be classified as a person-environment transactional process to create a more protective environment. At many personal meetings, when Marica told him about her problems. Mr. Reiners included a female teacher in the conversations because of Marica’s fear of being alone with older men (The stepfather tried to abuse Marica and often touched her indecently.). In doing so, Mr. Reiners demonstrated a very fine intuition. The code ‘speak from the heart’ (in German ‘Reden-können’) has a special meaning with regard to Marica’s resilience process. The opportunity to talk about her problems and experiences became an important coping strategy. Marica told of many other supporting situations. For example, Mr. Reiners established contact with a psychologist. He also told her not to feel so responsible for her siblings, but to focus on her own development. In this way he opened up some doors for her to feel better and rendered informal assistance to improve Marica’s situation.

This personal and emotional support influenced her school achievements. Marica’s motivation in school improved. A trustful teacher-student relationship correlates with a higher involvement at school (Schweer, 2000, p. 135), as is also shown in this study. As from the eighth class, Marica actively joined in lessons and enhanced her school performance. Mr. Hinrichs recognized Marica’s ability to care about others and her communication skills. He encouraged her to become class representative and Marica started to care about her classmates. Talking to others about similar experiences helped her to cope with her own adversity. Marica called this a ‘technique’ used by the teachers to get the best out of her. She had already developed the ability to care for others in her childhood. By transforming this risk condition (taking over the mother’s role) into a resource (aide for classmates, assuming responsibility), the teacher’s support helped to end the trajectory of suffering and initiate a creative metamorphosis of biographical identity. The assumption of responsibility generally appears to be a protective factor (Julius, & Goetze, 2000). Her awareness of other pupils’ problems was a main element of her creative metamorphosis of biographical identity. She was able to use her own adverse experiences to help others cope with their problems and to increase her own self-efficacy. Talking about problems became one of her main coping strategies. Another important coping strategy was to go in for sports. When she confided in Mr. Reiners, he advised her to take up sport as a way of channelling her energy. She was able to work off aggression and build up strength and has regularly played basketball for about two years.

Mr. Reiners and Mr. Hinrichs became important persons of trust. The pedagogical student-teacher relationship evolved into a more personal one. Both functioned as a significant other for Marica and had a great influence on her resilient development. They initiated a creative metamorphosis of biographical identity to overcome the risk conditions and help her to find adequate coping strategies. This phase of life is interpreted as a resilience process. The environment, in this case Mr. Hinrichs and Mr. Reiners, created a healthier and more protective environment (person-environment transactional process) so that Marica developed internal resilience factors (e.g. assumption of responsibility, school achievement, high motivation, emotional stability, positive self-awareness and self-efficacy). These factors had a great influence on her creative metamorphosis of biographical identity and promoted resilient development.

7. Conclusions for strengthening resilience in school

In the broadest sense, resilience processes are coping processes (Wustmann, 2005, p. 202). After a creative metamorphosis of biographical identity, the person regains biographical legal capacity and is able to envisage achievable biographical aims. The perception of stressors changes from this point of view into a challenging and positive perception. It seems possible to overcome the suffering phases of life. The person has regained her/his internal locus of control, which is assumed to be the basis for the origin of resilience (Wieland, 2011, p. 189).

Marica learned to use coping strategies to overcome neglectful conditions in the family. Her class teacher and her headmaster in secondary school initiated these coping strategies with the focus on her individual skills and risk conditions, and provided coping assistance (Perrez, Laireiter, & Baumann, 1998, pp. 293). Therefore, her trajectory of suffering came to an end and was transformed into a creative metamorphosis of biographical identity. The analysis has revealed that this biographical phase is related to resilience processes. In their roles of significant others, the teachers created a strong and trustful relationship with Marica and were able to strengthen her resilience.

These conclusions reinforce the role of teachers in the life of children at high risk. Constructive, trustful and approving teacher-student relationships are the basis for resilient development. Teachers can be significant others and an important protective resource when the family is a source of stress and adversity.

References

- Baker, J. A. (2009). Contributions of teacher-child relationships to positive school adjustment during elementary school. In Journal of School Psychology. Vol. 44, № 3, pp. 211-229.

- Bohnsack, F. (2009). Aufbauende Kräfte im Unterricht. Weinheim: Beltz.

- Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung (BZgA) (2009). Schutzfaktoren bei Kindern und Jugendlichen. Stand der Forschung zu psychosozialen Schutzfaktoren für Gesundheit. Köln: BZgA.

- Diers, M. (2014). Resilienzförderung in pädagogischen Beziehungen – Ein Projekt zur Verknüpfung von Biografie- und Resilienzforschung. In Prengel, A., & Winklhofer, U. (Eds.). Kinderrechte in pädagogischen Beziehungen. Band 2: Forschungszugänge. Opladen: Budrich, pp. 225-238.

- Diers, M. (2016). Resilienzförderung durch soziale Unterstützung von Lehrpersonen. Junge Erwachsene in Risikolage erzählen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Du Bois, D. & Silverthorn, N. (2005). Natural Mentoring Relationships and Adolescent Health: Evidence From a National Study. In American Journal of Public Health. Vol. 95, № 3, pp. 518-524.

- Fingerle, M. (2011). Resilienz deuten. Schlussfolgerungen für die Prävention. In Zander, M. (Ed.). Handbuch Resilienzförderung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 208-218.

- Grossmann, K., & Grossmann, K. (2004). Bindungen. Das Gefüge psychischer Sicherheit. Stuttgart: J. G. Cotta’sche Buchhandlung.

- Grotberg, E. H. (1995). A Guide to Promoting Resilience in Children: Strengthening the Human Spirit. URL: https://bibalex.org/baifa/Attachment/Documents/115519.pdf (retrieved: 2020, March 24).

- Hosser, D. (2001). Soziale Unterstützung im Strafvollzug. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Julius, H. ,& Goetze, H. (2000). Resilienz. In Borchert, J. (Ed.). Handbuch der Sonderpädagogischen Psychologie. Göttingen: Hogrefe, pp. 294-304.

- Kleemann, F., Krähnke, U., & Matuschek, I. (2009). Interpretative Sozialforschung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Kumpfer, C. (1999). Factors and Processes Contributing to Resilience. The Resilience Framework. In Glantz, M. D., & Johnson, J. L. (Eds.). Resilience and Development: Positive Life Adaptations. New York: Kluwer, pp. 179–224.

- Küsters, I. (2009). Narrative Interviews. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Laireiter, A. (2011). Diagnostik sozialer Unterstützung. In Tietjens, M. (Ed.). Facetten sozialer Unterstützung. Hamburg: Feldhaus, Ed. Czwalina, pp. 86-124.

- Masten, A. S. & Reed, M. (2002). Resilience in Development. In Snyder, C. R., & Lopez, S. J. (Eds.). Handbook of positive psychology. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, pp. 74-88.

- Nestmann, F. (2001). Soziale Netzwerke – Soziale Unterstützung. In Otto, H., Thiersch, H., & Böllert, K. (Eds.). Handbuch Sozialarbeit, Sozialpädagogik. Neuwied: Luchterhand, pp. 1684-1692.

- Nestmann, F., & Wehner, K. (2008). Soziale Netzwerke von Kindern und Jugendlichen. In Nestmann, F., Günther, J., Stiehler, S., Wehner, K., & Werner, J. (Eds.). Kindernetzwerke – Soziale Beziehungen und soziale Unterstützung in Familie, Pflegefamilie und Heim. Tübingen: DGVT-Verlag, pp. 11-40.

- Noack, P. (1990). Jugendentwicklung im Kontext. München: Psychologie-Verlags-Union.

- Perrez, M., Laireiter, A., & Baumann U. (1998). Streß und Coping als Einflußfaktoren. In Baumann, U. (Ed.). Lehrbuch klinische Psychologie – Psychotherapie. Bern: Huber, pp. 277-305.

- Pianta, R. C. (1992). Beyond the parent: The role of other adults in children’s lives. San Francisco: Jessey Bass.

- Rutter, M. (2006). Resilience Reconsidered: Conceptual Considerations, Empirical Findings, and Policy Implications. In Shonkoff, J. P., & Meisels, S. J. (Eds.). Handbook of early childhood Intervention. Cambridge: Second Edition, pp. 651–682.

- Schütze, F. (1983). Biographieforschung und narratives Interview. In Neue Praxis. Vol. 13, № 3, pp. 283-293.

- Schütze, F. (2005). Eine sehr persönliche generalisierte Sicht auf qualitative Sozialforschung. In Zeitschrift für Qualitative Bildungs-, Beratungs- und Sozialforschung (ZBBS). Vol. 6, № 2, pp. 211-248.

- Schütze, F. (2014). Autobiographical Accounts of War Experiences. An Outline for the Analysis of Topically Focused Autobiographical Texts – Using the Example of the “Robert Rasmus” Account in Studs Terkel’ s Book, “The Good War”. In Qualitative Sociology Review. Vol. X, № 1, pp. 224-283.

- Schweer, M. K.W. (2000). Vertrauen als basale Komponente der Lehrer-Schüler-Interaktion. In Schweer, M. K.W. (Ed.). Lehrer-Schüler-Interaktion – Pädagogisch-psychologische Aspekte des Lehrens und Lernens in der Schule. Opladen: Leske + Budrich, pp. 129-138.

- Shumaker, S. A., & Brownell, A. (1984). Toward a Theory of Social Support: Closing Conceptual Gaps. In Journal of Social Issues. Vol. 40, № 4, pp. 11-36.

- Theis-Scholz, M. (2007). Das Konzept der Resilienz und der Salutogenese und seine Implikationen für den Unterricht. In Zeitschrift für Heilpädagogik. Vol. 7, pp. 265-273.

- Thoits, P. A. (1982). Conceptual, Methodological, and Theoretical Problems in Studying Social Support as a Buffer Against Life Stress. In Journal of Health and Social Behavior. Vol. 23, № 2, pp. 145-159.

- Unger, M. (2018). Systemic resilience: principles and processes for a science of change in contexts of adversity. Ecology and Society, Vol. 23, № 4, p. 34.

- Werner, E. E. (2006). Protective Factors and Individual Resilience. In Shonkoff, J. P., & Meisels, S. J. (Eds.). Handbook of early childhood Intervention. Cambridge: University Press, pp. 115-132.

- Wieland, N. (2011). Resilienz und Resilienzförderung – eine begriffliche Systematisierung. In Zander, M. (Ed.). Handbuch Resilienzförderung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 180-207.

- Wustmann, C. (2004). Resilienz. Widerstandsfähigkeit von Kindern in Tageseinrichtungen fördern. Weinheim: Beltz.

- Wustmann, C. (2005). Die Blickrichtung der neueren Resilienzforschung. In Zeitschrift für Pädagogik. Vol. 51, № 2, pp. 192-206.

About the Author

Dr. Manuela Diers: Teacher, Integrated Comprehensive School, Peine (Germany); scientific interests: school pedagogy, children’s rights and resilience and biography research; e-mail: manuela.diers@gmx.de

i All names have been changed in order to protect the individuals’ anonymity.

ii To read about the detailed case of Hung and David, see Diers, 2016. The case analysis of David is also published in Diers, 2014.