Abstract: In this paper we explore collaboration in the context of the educational services industry (ESI). We look to literature from the communication field to consider ethical strategies and methods for ensuring the validity of the outcomes of collaborative working. Drawing on Collaborative Product Development and conversation theory we devise four principles that can guide the collaborative process within an education-based partnership project. We then use a case study to consider how these principles supported the outcomes of a cross-national partnership project. Finally, we draw on these principles to consider the lessons for project management in education public private partnerships.

Keywords: Curriculum review, public-private partnerships in education, Education Services Industry, collaboration, Collaborative Product Development (CPD)

摘要(SinéadFitzsimons和Martin Johnson: 如何使用合作项目开发理论为国际课程计划伙伴关系提供指导):在本文中,我们研究了与教育服务产业(ESI)相关的合作。我们从传播领域看文献,用来考虑道德策略和方法,以确保合作结果的有效性。以协作产品开发和对话理论作为基础,我们开发了四个原则,它们可以指导在基于教育的伙伴关系项目中的协作过程。而后,通过案例研究,我们将探讨这些原则是如何支持跨国伙伴关系项目的成果的。最后,我们借鉴这些原理来探究为了项目管理

在教育领域中公私合作伙伴关系而进行的课程。

关键词:课程审查,教育公私伙伴关系,教育服务产业,合作,协同产品开发(CPD)

摘要(SinéadFitzsimons和Martin Johnson: 如何使用合作項目開發理論為國際課程計劃夥伴關係提供指導):在本文中,我們研究了與教育服務產業(ESI)相關的合作。我們從傳播領域看文獻,用來考慮道德策略和方法,以確保合作結果的有效性。以協作產品開發和對話理論作為基礎,我們開發了四個原則,它們可以指導在基於教育的伙伴關係項目中的協作過程。而後,通過案例研究,我們將探討這些原則是如何支持跨國夥伴關係項目的成果的。最後,我們藉鑑這些原理來探究為了項目管理

在教育領域中公私合作夥伴關係而進行的課程。

關鍵詞:課程審查,教育公私伙伴關係,教育服務產業,合作,協同產品開發(CPD)

Zusammenfassung (Sinéad Fitzsimons & Martin Johnson: Wie die Theorie der kooperativen Projektentwicklung genutzt werden kann, um Anleitungen für internationale Lehrplanpartnerschaften zu geben): In diesem Papier untersuchen wir die Kooperation im Zusammenhang mit der Bildungsdienstleistungsindustrie (ESI). Wir schauen auf Literatur aus dem Kommunikationsbereich, um ethische Strategien und Methoden zur Sicherstellung der Gültigkeit der Ergebnisse der Zusammenarbeit zu betrachten. Auf der Grundlage der kollaborativen Produktentwicklung und der Konversationstheorie erarbeiten wir vier Prinzipien, die den kollaborativen Prozess innerhalb eines bildungsbasierten Partnerschaftsprojekts leiten können. Anhand einer Fallstudie betrachten wir dann, wie diese Prinzipien die Ergebnisse eines länderübergreifenden Partnerschaftsprojekts unterstützt haben. Schließlich ziehen wir diese Prinzipien heran, um die Lehren für das Projektmanagement in öffentlich-privaten Partnerschaften im Bildungsbereich zu betrachten.

Schlüsselwörter: Lehrplanüberprüfung, öffentlich-private Partnerschaften im Bildungswesen, Bildungsdienstleistungsindustrie, Zusammenarbeit, kollaborative Produktentwicklung (CPD)

Резюме (Синеад Фитцсимонс, Мартин Джонсон: Как эффективно использовать теорию кооперативного проектного развития, чтобы успешно консультировать по вопросам международного сотрудничества в аспектах разработки учебных планов): В данной статье мы рассматриваем сотрудничество во взаимосвязи со сферой оказания образовательных услуг. При этом мы обращаемся к источникам из сферы коммуникации, чтобы рассмотреть этические стратегии и методы обеспечения валидности результатов кооперации. На основе концепции коллаборативного развития продукта и теории общения мы разрабытываем четыре принципа, которые управляют процессом коллаборации в рамках образовательного партнерского проекта. Далее на примере конкретного исследования мы изучаем, как эти принципы улучшают результаты международной кооперационной деятельности. В заключение мы еще раз обращаемся к данным принципам, чтобы рассмотреть стратегии проектного менеджмента в общественно-частных партнерствах, закрепленных в образовательной сфере.

Ключевые слова: контроль и ревизия учебных планов, общественно-частное партнерство в образовательной сфере, оказание образовательных услуг, сотрудничество, коллаборативное создание продукта

Introduction

As transnational connections and multinational collaborations increase across many industries and fields, it is not surprising that the education industry is also becoming increasingly globalised (Verger, Lubienski, & Steiner-Khamsi, 2016). This industry, often referred to as the Educational Services Industry (ESI) or the Global Education Industry (GEI), is a growing international sector that includes, but is not limited to, the global market that has been created for the production, exchange and consumption of educational resources, services, expertise and qualifications (Ball, 2007; 2012; Verger et al., 2016). One area of this industry is international consulting services. Education consultants can specialise in a range of areas and depending on their expertise will market their services to learners, parents, teachers, administrators or government bodies around the world. Education consulting services have also become more common in international development projects which incorporate education reform. Robertson, Mundy, Verger, & Menashy (2012) argue that this trend links to changes that have occurred in the governance of education since the 1990s. Since this time, international institutions, governments, firms, philanthropies and consultants have promoted partnerships involving new combinations of state and non-state actors working together to develop the education sector. These interactions often operate across local, regional and national contexts.

These cooperative partnerships, sometimes referred to as Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) (Robertson et al., 2012), offer rich opportunities to share expert knowledge and skills between global and local experts in order to foster positive and sustainable education development. However, positive and sustainable educational development is not a guaranteed outcome of international PPPs. For example, global education partnerships can lead to an increased risk of privatisation of education (Machingambi, 2014); unequal distribution of resources, neo-colonial pressures (Anwarudin, 2014) and the erosion of indigenous culture (Brock-Utne, 2012). These risks can also lead to high levels of social tension and can perpetuate social divisions (Cambridge University Press & Cambridge Assessment, 2019).

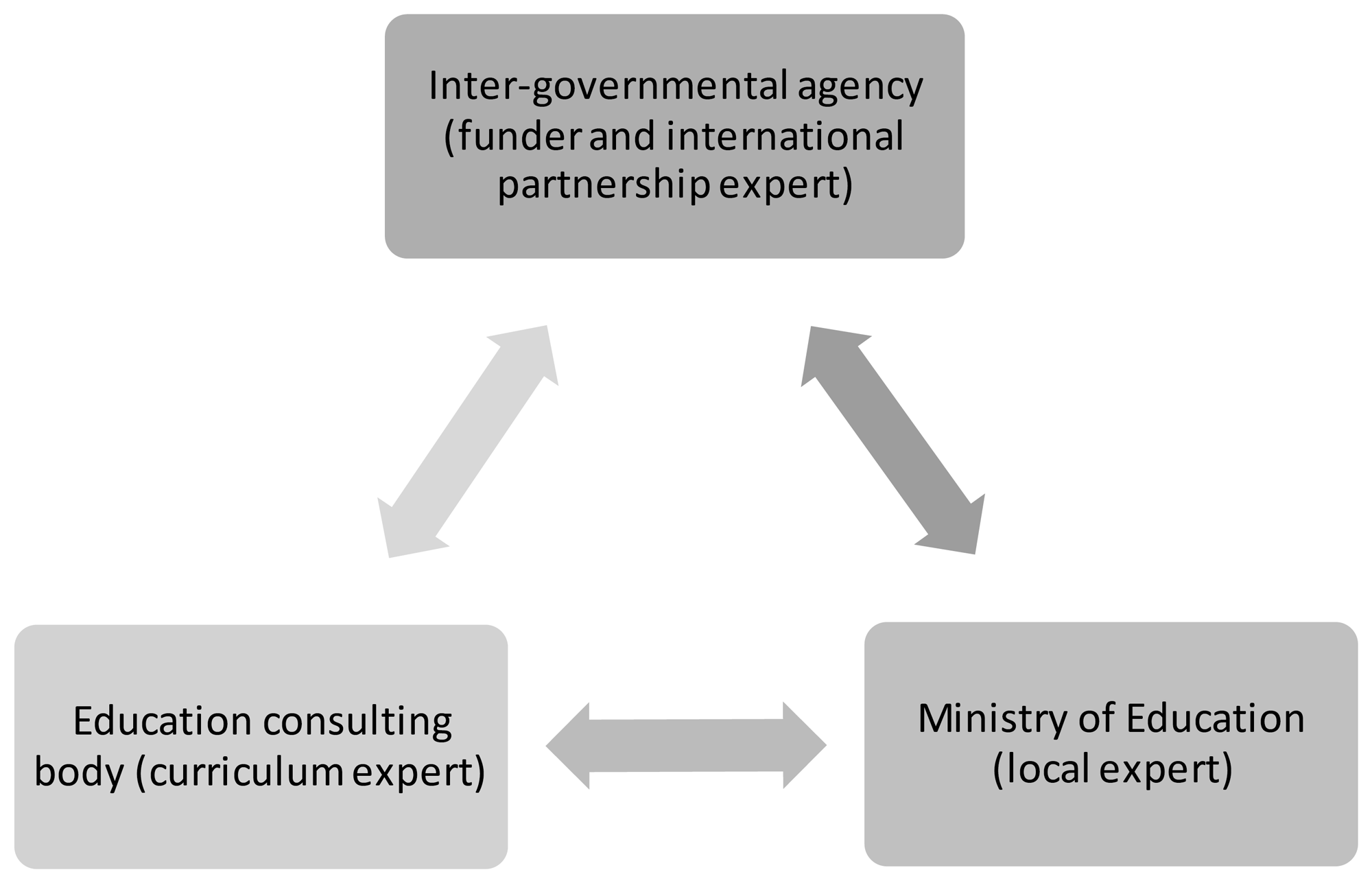

Literature on research-informed collaboration strategies relating to development projects funded by third party groups, such as inter-governmental agencies, but carried out by international experts and local stakeholder groups, such as Ministries of Education (MOEs), is sparse. However, this increasingly popular form of PPPs are worthy of consideration. This triangular approach to international educational development (Figure 1) creates rich opportunities regarding funding and shared expertise. Yet, it can also create challenges relating to prioritising local needs and perspectives, as well as fostering authentic collaboration between all groups. In these types of PPPs, local experts and international education consultants are co-partners in achieving the desired aim of the project. This paper will focus on this relationship and how an effective and collaborative partnership can be fostered.

Since there is currently a limited amount of academic literature available relating to effective approaches for transnational PPPs in the education sector, we argue that drawing from models of Collaborative Product Development (CPD) and conversation theory can provide valuable insights for how authentic and effective collaboration can be fostered in an education-based PPP. Through reviewing key literature, a conceptual CPD model, and conversation theory concepts such as epistemic stance and epistemic access, this article will investigate how an effective, equitable and ethical partnership was actively fostered in an international PPP project. We argue that paralleling a transnational PPP with conversation theory and a conceptual CPD model (Arsenyan, & Buyukozkan, 2014) provides effective collaboration principles for project managers wishing to foster effective, ethical and valid international partnerships in the field of ESI. Through sharing trialled strategies and underpinning research, we aim to present effective collaboration principles to establish valid authentic collaboration in hopes that this can provide insight to future international education projects.

Method

To investigate effective methods of collaboration for international PPPs within the education sector, we conducted a thorough literature review of international education development and considered publications and guidance material created by non-governmental agencies and inter-governmental agencies on the topic. Specifically, we focused on literature that discussed ethical collaboration strategies and methods for ensuring validity of the collaborative project design. As the literature in this area is limited, we began to look beyond literature pertaining to education-based projects to wider fields featuring equitable collaboration and communication.

We first considered conversation theory since an effective conversation can provide insight into effective communication strategies. Whilst conversation analysis has not developed a clear, systematic approach for analysing ‘action formation’ (Heritage, 2012a), which refers to the ways in which turns at talk attain recognisable actions, Mercer’s (2005) and Littleton & Mercer’s (2013) work using sociocultural discourse analysis has gone some way to outline how the use of open, exploratory talk can support the attainment of shared outcomes through fostering collective ‘interthinking’. Within conversation theory, the concepts of epistemic status and epistemic status were also insightful. Heritage (2012a) argues that effective and ethical communication must ensure that a minimum level of understanding is established across participants and that epistemic access is ensured, meaning everyone is given the appropriate information and access to the required knowledge needed to actively contribute and understand the communication (Heritage, 2012a). This is not to say that everyone will have an equal level of knowledge. In this way, those who hold specific knowledge and skills should be respected for their higher epistemic status relating to a particular area and called upon to share their expertise with those involved in the partnership. Epistemic status should shift depending on the topic or area of knowledge being considered (Heritage, 2013). For example, an international education specialist may have a higher epistemic status when discussing international policy, however a local educator will have high epistemic status in terms of relevance and value of international policy in the country context.

Exploring these elements of conversation theory were insightful, however they did not provide a feasible method for developing communication principles since in order to truly assess the quality of communication using conversation theory, a detailed discourse analysis of spoken dialogue would be required. This would have to take place after a cross-partner interaction occurred. Although this would provide valuable insights and will be discussed as an option for further research in the conclusion of this article, what our research team sought was guidance to inform collaboration principles which could be incorporated into PPP planning from its outset.

Our literature search also revealed an article by Krishna and Morgan (2004) entitled, “The art of conversation: eliciting information from experts through multi-stage communication.” This article applied Collaborative Product Development (CPD) and the field of game theory into conversation analysis. Game theory is the study of conflict and/or collaboration between individuals and/or institutions. It focuses on how interacting choices are a result of partner preferences and lead to specific outcomes depending on how these choices (often related to cost-benefit) manifest in interactions (Arsenyan, & Buyukozkan, 2014). Drawing on the CPD model devised by Arsenyan, Buyukozkan, & Feyzioğlu (2015), we developed a set of communication principles which can be applied to education-based PPPs, especially those relating to curriculum development projects.

To test the validity of these principles, we applied them to a 2019 case study. The case study involved an international PPP that included a UK-based university department where the authors were located, an intergovernmental funding agency, and a ‘foreign’ MOE located on a different continent from the authors. By ‘foreign’, we are referring to an education jurisdiction that is at a physical, cultural and contextual distance from the authors. Due to confidentiality agreements, the exact identities of these two partners cannot be shared. The aim of the project was for the university department to support the MOE in reviewing their national curriculum in order to identify strengths and weaknesses and to identify key areas for the MOE to reflect on, develop or replace. The intention was that the outcomes of this review could be used to guide and inform decisions in the Ministry’s upcoming national curriculum revision. A key focus of this project was to ensure that this partnership between the MOE and the university curriculum consulting group was driven by the wishes and needs of the MOE. The role of the university team was to offer international expertise and to support capacity development, but to not impose perspectives or specific education practices. In order to do this effectively, authentic collaboration had to be fostered. For this reason, this PPP serves as an excellent case study to investigate ethical and valid communication and collaboration principles.

Curriculum review as an international education service

Conducting a curriculum review is an important component of any curriculum enhancement process. Leading from Stenhouse’s (1975) definition of a curriculum as an attempt to communicate the essential principles and features of an education system in a form that is effective in practice, a curriculum review can be seen as an evidence-based analysis of what principles are being prioritised by an education system and how these principles are being conveyed to the learner (Gillies, 2006). Generally, a curriculum review involves an in-depth analysis of curriculum documents and resources, including policies, how these elements are put into practice in the classroom and what outcomes they lead to. Curriculum reviews can be conducted in a variety of ways and can vary in depth, breadth and level of stakeholder involvement. However, curriculum reviews are often believed to be strongest when they involve a consultative and collaborative process (Briggs, 2007; Reid, 2005; Barber, Chijioke, & Mourshed, 2010). Typically, the main groups who tend to be consulted in a national curriculum review process are senior teachers, senior administrators, elected local authorities, subject matter experts, university scholars and, in some cases, feedback from the general public (Levin, 2008; Hussain, et al., 2011). However, the breadth and depth of stakeholder collaboration is often limited by the time and resources allocated to the curriculum review process. Unfortunately, policy and curriculum change is frequently undertaken with poor regard for the contextual realities of practitioners that are situated closest to curriculum implementation (Chisholm, 2005).

Investigating the parameters of an effective curriculum review is becoming increasingly important as some believe there has been an epidemic of education reform over the last two decades with a sprawling, and often contradicting, array of curriculum theory (Paraskeva, 2018; Priestley, 2005; Dale, & Robertson, 2002). Dale and Robertson (2002) have suggested that curriculum restructuring has been an increasingly global agenda for education which often disregards national practices or policies. However, there is limited academic literature regarding how to conduct a curriculum review that is relevant, effective and aligns with national priorities. Priestley (2005) argues that contemporary reforms have often followed a top-down, centre-periphery model of decision making and dissemination. This lack of appropriate stakeholder consultation or theoretical consideration has negatively impacted on the coherence of curriculum development which has led to a theoretically agnostic approach to curriculum development (Priestley, & Humes, 2010). This absence of a quality curriculum review due to a lack of stakeholder consultation has also led to curriculum development initiatives being developed and delivered in ‘ignorance or defiance of teachers’ beliefs and missions’ (Goodson, 2003, xiii). We argue that for ethical and valid education-based PPPs, the local voice should not just be seen as a stakeholder, but as a collaborative and equal partner that holds invaluable knowledge, skills and insights.

UNESCO (2013, 2017) promotes a three-step approach to curriculum review. The first step involves reviewers examining a range of curriculum documents, textbooks and other materials widely used in the classroom for coherence, quality, breadth and depth. This step may also involve a comparative study where curriculum documents are mapped against other jurisdictions’ documents in order to highlight similarities and differences. This process is often referred to as curriculum mapping (Greatorex, et al. 2019). The second step focuses on examining teaching practices, school conditions and resources, pupil performance data and considering the perspectives of key stakeholders such as teachers, parents, school administrators and students. When conducting a system wide review, ideally a range of schools, ages and abilities are considered within the review in order to build a realistic picture of how education is being experienced across a wide range of learners. UNESCO (2013, 2017) positions the curriculum review as a necessary component of any curriculum development process since it provides developers with the vital information needed to understand the current situation of the education provision. The third step of UNESCO’s proposed curriculum review process involves conducting a participative curriculum review workshop which allows a variety of stakeholders to analyse findings from step 1 and 2, and then to draw conclusions and potentially form recommendations for curriculum change. The goal is to bring these various methods of inquiry together in order to arrive at a consensus of how best to further enhance the curriculum (Levin, 2008). UNESCO (2017) argues that the curriculum review process should be the responsibility of the people who are experienced in current curriculum provisions and are aware of its strengths and weaknesses within the context in which it is applied. In this way, ‘local’, which we use to refer to those for whom the curriculum is designed, contribution is essential.

The inclusion and exclusion of particular groups as stakeholders can be a very contentious decision in the curriculum review process (Chisholm, 2015). Haider (2016) argues that there is a need to involve practitioners in curriculum review and curriculum development in order for the development to be successful. For example, in the 2005 South African curriculum review, the decision to not include any teachers or teacher union representatives was highly criticised (Chisholm, 2005). As a result, South African teachers were wary of the change and did not actively support its success (Taole, 2013). These findings highlight that curriculum change is unlikely to happen unless the review and development process actively engages those who are directly involved in applying effective reform and have awareness of contemporary classroom realities (Cuban, 1998) since they are the critical change agents and stakeholders for curriculum implementation (Taole, 2013).

The challenge of accessing local insights and perspectives has amplified since curriculum reviews increasingly involve international experts for guidance and consultation. In curriculum development practice there is a well-established tradition of employing cross-national comparison work for trying to understand the qualities of different education systems (e.g. Barber, & Mourshed, 2007; Elliott, 2014; de Bruyckere, 2013; Schmidt, 2004) . These cross-national comparisons and consultations are one aspect of the rapidly expanding Education Services Industry (ESI), which includes education companies and ‘edupreneurs’ (Ball, 2007). ESI works across various levels and forms of education including curriculum development, delivery, management, training and professional development (Ball, 2007). In many cases, especially in developing countries, international experts are being contracted to support or lead the curriculum development process. In more extreme cases, the international consultant imports models and curriculum from other contexts without adaptation.

Curriculum review and development research presents an opportunity for transnational working that can offer a number of benefits. One of the benefits of this type of approach is that it provides an opportunity for those outside of a system to offer a perspective that is a resource for reflection for those within the system. This external perspective enables trends and patterns to be recognised that may be overlooked from those within the system (e.g. their perspective may be framed by a long-standing and taken for granted cultural view). In addition, engagement with external actors offers an opportunity to draw in expertise from those who have been through curriculum development, and who may have insights into the challenges and issues around such an experience.

At the same time, the opportunities outlined above need to be balanced against the challenges that also relate to working outside of the context in which the curriculum is implemented. Yates (2016) highlights that it is important to recognise both the big picture and the localised perspectives in curriculum review work. Where a researcher’s proximity to a context of study is significant, it is possible that nuanced meanings around a curriculum can be difficult to rationalise. To paraphrase Goffman (1961) , it is difficult to understand the logic of behaviours from a distance, even though those behaviours make complete sense to the participants who are located in a specific context. Another challenge relates to the work that is needed to establish effective communication across remote contexts. There is a persistent and longstanding literature about how the problems of interruption, lag, lack of paralinguistic data, and narrow bandwidth can undermine meaningful sense making (Bower, 2008; Brennan, 1998; Condon, & Čech, 2010; Daft, & Lengel, 1986; Dennis et al., 2008; Gaver et al., 1993; Honeycutt, 2001; Joiner, & Jones, 2003; Lemley et al., 2007) . When conducting a review of a foreign curriculum, we argue that there is an additional initial step which must take place. In these international projects, the first step should be a collaborative mission shaping consultation which allows the local partners to inform their international partners of their aims and vision. This could include elements such as:

- The role they believe their education provision should fulfil

- Their educational priorities

- Strengths and weaknesses that they currently witness in their curriculum

- Their vision for the future of education in their country or jurisdiction

- Important documents, policies and stakeholders that they believe should be considered in the review process

Many of these areas may involve contentious local issues which sometimes leads to international consultants acting as a mediator between opposing views. If contextual specificities and realities are ignored, the possibility for a smooth and efficient development process is greatly limited since a curriculum must evolve according to the needs of the specific learners, society and context in which it will be delivered (Haider, 2016). In this way, collaborating with local partners and stakeholders is essential for fostering ethical and sustainable educational development. Local partners also hold valuable insights into the lived curriculum (Rahman & Missingham, 2018).

When conducting curriculum review through an international partnership, the necessity to gain this insight is significantly heightened. Stakeholder perspectives are an important contribution to evidence-informed policy research (EIPR) (Burns, & Schuller, 2007). National stakeholders, who can be seen as jurisdiction experts, working collaboratively with international experts will have the ability to sift through the vast amounts of available information and data and select the evidence that is most applicable and reliable for conducting a review that leads to effective recommendations. This collaboration with the jurisdiction experts and the international experts has the potential to create a powerful partnership. As UNESCO (2017) states in their curriculum development guidance, all decisions in the curriculum development process must be based on real information. This information does not necessarily have to be empirical or quantitative, but it must be of ‘sufficient substance to provide reliable and valid advice to curriculum decision makers’ (UNESCO, 2017, p.7).

Although there is literature relating to accessing stakeholder voices in education development projects, there is little literature relating to how to work collaboratively with local partners as equals in the project planning phase. Decisions must be made regarding how collaboration should be fostered and which partner should lead on particular aspects of the project. These decisions will have an impact on the curriculum review process since the interactions involved at this phase of the process will greatly influence the quality of the review’s outcome (Chisholm, 2015). Boreham’s (2004) work on organisational learning suggests that successful change is more likely if spaces are opened for dialogue and if power relationships are reconstituted in order to provide equal voice for the individuals enacting change. Although initially intended as a technology-centred process and used primarily by economists, CPD theory offers valuable insights into how authentic collaboration can be fostered. According to CPD, collaboration must emphasise the widespread involvement and interdependence between partners at all levels, frequent and regular information exchange, integration of business processes and joint work and activities (Lamming, 1993).

Reflecting on authentic collaboration using CPD theory

There is a developing field of research that considers the ways that professionals interact within and across organisations (e.g. Cooren et al., 2011; Willis et al., 2010) . When focusing on the interactions associated with a curriculum review, these interactions are fundamentally linked to authentic collaboration and are essential in ensuring the validity of the review process. From a curriculum and assessment perspective, validity is concerned with the links between information, interpretation, and action. Validity, therefore, describes the relationship between data and the interpretations and actions that derive from those interpretations. When applied to the case study curriculum review project with the MOE, validity pertains to whether a valid and ethical method for fostering collaboration has been employed, thus enabling a valid outcome – an accurate and applicable curriculum review. CPD theory can provide valuable guidance for how this can be achieved.

In many situations, those with the power to make decisions lack important knowledge or skills about the consequences of their choices. As a result, decision makers tend to consult relevant experts before making final decisions (Krishna, & Morgan, 2004). Although Krishna and Morgan are focusing on technology development, there are transferable elements that provide insight for education-based PPPs. Considering literature within the field of CPD tells us that ensuring active collaboration by the decision makers and the experts through multiple stages of communication leads to higher rates of knowledge transfer and more optimal outcomes in the partnership (Krishna, & Morgan, 2004).

Camarinha-Matos and Abreu (2007) argue that in order to maintain competitive advantage and sustainability in rapidly growing markets, firms seek to collaborate with other firms in order to enhance their product development efforts. These collaborative networks encourage sustainability and also increase the chances of product improvement through the pooling of knowledge and expertise. Littler and colleagues (1995) have found that more and more firms engage in collaborations in order to improve quality and benefit from complementary knowledge. In this way, sharing knowledge is seen to increase efficiency of the project as opposed to slowing down the development process. Therefore, CPD emerges as a way for organisations to increase efficiency and effectiveness. This is similar to some of the motives behind funding educational PPPs discussed above.

In our case study, we apply CPD theory to go beyond product development and to include idea development. When applying this to a curriculum review process, the ‘product’ that is being developed pertains to the ideas that are devised around what methods of data collection and analysis should be used during the review process. These methods will inevitably impact the curriculum recommendations that emerge from the review and will eventually influence the outcome of any curriculum changes that occur in light of the review.

There are many valuable insights that emerge from CPD literature that can be applied to education-based PPPs. For example, Goyal and Joshi (2003) recognise that CPD does not solely result in an enhanced project. Like education-based PPPs, CPD partnerships can also lead to the creation and sharing of knowledge, the setting of new standards and the sharing of facilities and resources. The incentive to collaborate goes far beyond the creation of the final product (Bhaskaran, & Krishnan, 2009), whether it be a technological tool or a curriculum review report. The product itself has a specific use and applicability. However, the knowledge and skills that are acquired through the process can influence future thinking and can significantly impact on how the organisation works overtime.

We argue that applying effective CPD approaches can help to foster a collaborative epistemic stance between partners. ‘Epistemic stance’ refers to the moment-by-moment expression of epistemic status within relationships (Heritage, 2012b). However, much of this is linked to context specific, sociocultural norms. This is why Littleton and Mercer (2013) argue that sociocultural discourse analysis should be taken into consideration when critically analysing any group interaction. Therefore, instead of drawing on the mathematical models employed by game theorists, we take a more contextualised stance and argue that sociocultural reflexivity is more effective for ensuring a successful education-based PPP than relying on a mathematical model of cost and benefit. This is also true since the ‘products’ or methodological ideas that are being focused on are not technological in nature, nor are they primarily concerned with market value. Instead they focus on supporting high quality education systems. We argue that education itself is situated within sociocultural realms. Although certain knowledge and skills transcend sociocultural boundaries, the delivered curriculum must be able to successfully function within, and is arguably a product of, the society it is developed for.

Drawing from Arsenyan and Büyüközkan (2014), successful CPD is assumed to be based on effective collaboration. In their model, effective collaboration is based on four sub-dimensions including trust, coordination, co-learning, and co-innovation (Arsenyan & Büyüközkan, 2014). Combined with Littleton, & Mercer’s (2013) ideas of effective interthinking and exploratory talk, we devised four principles to guide the collaborative process of the curriculum review:

- Trust: Relevant knowledge and information should be shared. The specific knowledge, perspectives and skills of each partner should be trusted as having value.

- Coordination: Partners should be working towards a common goal. Differences in time, space, sociocultural environment and resources should be taken into account and appropriately accommodated to ensure a common goal can be worked towards.

- Co-learning: There must be a recognition that upskilling and knowledge acquisition will occur on all sides of the partnership, with the epistemic status of partners shifting depending on the skill and knowledge that is required. Co-learning also involves the ability for different parties to challenge and critique one another in a constructive way. Co-learning should not only be planned in the early phases of the project, but should also occur organically as particular knowledge and skills emerge as being valuable.

- Co-innovation: The final ‘product’ should be a result of co-innovation, which means it should be a collaborative process that results in innovative and bespoke solutions that specifically emerge as a result of the collaboration.

These four principles guided the collaborative process of the project. We will now go deeper into the case study and how these four principles were applied. We will then reflect on their effectiveness in fostering valid collaboration in education-based PPPs.

Case study

The context for the case study is a large, multi-strand curriculum review project for a foreign Ministry of Education (MOE). The project had a multi-partner dimension that included a UK-based university department that was commissioned to provide a range of observations and recommendations to inform the work of a funding intergovernmental agency and the curriculum development body of an MOE about possible areas of the curriculum that required reform.

In order to provide a comprehensive review of the curriculum in the country of focus, the university department designed a project that included a series of stages. These stages involved a variety of methods that would cumulatively build a picture of the country’s curriculum programme. These stages included a policy analysis, a detailed evaluation of the local curriculum, a review of selected curricula from other countries, stakeholder consultations and an analysis of system capacity.

As part of this broad project the authors contributed to the curriculum review task. This involved carrying out a review of different curricula so that the MOE could see their own curriculum in relation to those of other jurisdictions. A key feature of the review design was that it needed to include capacity development for the MOE’s curriculum body so that they could continue with the curriculum review process once the partnership was complete. To ensure that this authentic transfer of knowledge and skills took place, three workshop meetings were planned during the project lifetime.

These workshops served as pivotal points in the project’s progress as they established a collaborative working space, enabled capacity building for all partners involved, and brought an increased level of validity to the project’s final output. The workshops were an opportunity to: (1) present their established method of curriculum analysis; (2) to develop the capacity of the local participants to design and use a method of analysis that was applicable and effective in the study context; and (3) to select the curricula that would be analysed so that the most useful insights were gathered.

Prior to the workshops, analysis had been carried out to gauge the current educational conditions in the country, and these analyses included data from the policy analysis and the local curriculum content review. There had also been a range of stakeholder consultation activities and project team conversations to gather perspectives around the current educational provision and around any aspirations for future development across national, regional, and local levels. The workshops were informed by the outcomes from these earlier phases of work and were expected to feed into an overall synthesis report.

To achieve these aims, specific workshop planning and implementation strategies were put in place. The process used to prepare, facilitate and reflect on the workshop can be connected to the four principles derived from CPD theory (discussed above) as a way to ensure equality and collaboration.

- Trust: An important component of trust building related to setting the conditions whereby an equality of voice could be attained. For our development this involved organising it so that a member of our university team could spend time in the host location of the curriculum initiative (the ‘visiting lead’). As part of this physical presence the university representative had the opportunity to engage directly with the MOE team. Whilst this engagement involved the visitor being sensitive to the appropriate social norms of the host context, it also involved important reciprocal cultural exchange with the university representative being taken to locally valued social events by the MOE team. This social engagement also allowed all of the group to get to know each other. Morgan & Symon (2002) note that open workplace communication leads to trust, and they acknowledge that this is difficult to construct remotely. This point coheres with arguments drawing on media richness theory (e.g. Daft, & Lengel, 1986; Trevino et al., 1987) , which suggests that team trust (and performance) is improved when participants have access to more information about each other. Martins et al. (2004) observe that this often includes social and informal (i.e. non-work-specific) information about other work colleagues. Another component of communication that we attended to was to ensure that we dealt with questions or requests for information from the MOE as quickly as possible. The fast return of information when engaged with remote interactions sends a message that these requests are being prioritised, and by connection, that the relationship is valued. This also helps to ensure that a vacuum of information is not created in which distrust can grow.

- Coordination: As well as the communication issues covered in the previous point, the attainment of coordination requires that the partners should be working towards a common goal. This goal focus can be considered to be a macro-level consideration. To attain this, differences in time, space, sociocultural environment and resources should be taken into account and appropriately accommodated. Taking an ethnomethodological perspective, which underpins much conversation theory (e.g. see Heritage, 2001) , the attainment of the macro level goals requires a focus on micro level interactions (Goffman, 1963) . In essence, this is an appeal to consider how the participants interact at the micro level to ‘live’ the macro level goals. One such interaction, which we have alluded to above, is to ensure in the planning stage that there is an opportunity at times for physical collocation of team members from across the distributed teams. We also acknowledge that collocation is not possible in all cases, which means that there is a requirement to consider the conditions of the remote interactions at the project planning stage, which in our project involved email or telephone/video communication. For our project we ensured that we planned times for interaction that were sensitive to the time differences of all of the partners. This ensured that one institution did not take priority, as this could signal a lack of parity of status between the partnership institutions. We also ensured that we considered the working patterns of the participating partners, so as not to schedule work that disregarded important cultural norms, such as worship or rest days or national holidays.

- Co-learning: For this principle there must be a recognition that upskilling and knowledge acquisition will occur on all sides of the partnership, with the epistemic status of partners shifting at different parts of the project, depending on the skill and knowledge that is required. Co-learning should not only be planned in the early phases of the project but should also organically occur as particular knowledge and skills emerge as being valuable. In our project we planned that the workshops would be opportunities for rich interaction for sharing some of the expertise that we could contribute to the partnership. One thing that we wanted to encourage was a tangible transfer of practical knowledge. Specifically, our university department has expertise in research methods that can be used to compare curricula. As part of our contribution to the development we created a document that outlined the methodological steps for carrying out a curriculum review exercise. We also devised a series of interaction and collaborative exercises that could be carried out in a workshop with MOE team members so that this rationalised methodology could be contextualised and discussed. This document can be seen to represent a boundary object (Star & Griesemer, 1989) since the document was useful for focusing the disparate teams on common processes. It also provided a platform for decision making in a divided labour situation, which is a common feature of PPPs. For example, the methodology document that we provided allowed the local partnership team to consider who had the most appropriate expertise to complete the different task elements, such as curriculum document data collection, stakeholder consultation to decide which curriculum elements should be the focus for the review, and how to deal with the analysis of these elements.

- Co-innovation: the final CPD feature highlights that the final ‘product’ of the partnership will be a result of co-innovation. This means that the collaborative process will result in innovative and bespoke solutions. A consequence of the iterative process of creation is that it is unlikely that the specific outcomes of the process can be anticipated in advance. The structuring for this emerging process is the shared common goal that is the focus of the partnership. By returning to the aims of the development it is possible for the partnership to work to a common goal as new decisions need to be made in the light of unfolding events. For example, the choices around which curriculum elements to review will have consequences in terms of decisions about the timing and resources required, particularly where resource availability is likely to be limited. Having the project aims as a joint reference point allows the partners to come to compromises about how best to achieve the desired common outcomes (e.g. how many elements from how many curriculum documents should be reviewed). This process of interaction conforms to the notion of ‘interthinking’ (Littleton, & Mercer, 2013) , where participants combine their collective thinking. Achieving interthinking, which in a way represents a form of co-learning as participants come to see the problem from the perspective of others, requires the conditions of trust and coordination which are also outlined as elements of CPD. This point demonstrates the extent to which CPD is an integrated model rather than being a collection of separate elements.

In order to assess the effectiveness employing these principles, the project team integrated various methods of participants’ feedback (see Table 1).

Table 1: Forms of feedback captured by the project team in order to assess the level of authentic collaboration gathered.

| Medium of feedback | Extract |

|---|---|

| Survey | Prior to the workshop, participants were asked to feedback on what elements they would like to see included in a curriculum review workshop. During and after the workshop, participants were also given a feedback form which asked if they acquired new knowledge and skills and, if yes, how they would be able to apply them. They were also asked how useful each component of the workshop was. Overall, the feedback was positive and constructive. |

| Visiting lead’s diary | The visiting lead kept a reflective diary which was shared with the wider project team. This diary was written daily and included notes of important conversations, insights and observations that occurred throughout the in-country work. The diary helped the visiting lead to understand, process and consider some of the information they received. For example, one entry reflected on the reform process explaining that political tension between some groups was leading to certain groups’ opinions being ignored. They then brainstormed ways to consult these different groups in a mediating manner. |

| Email correspondence | Email correspondence was another important medium for gathering feedback and for ensuring effective collaboration. Emails were collected, stored centrally (protecting any GDPR issues) and reviewed. In addition, follow-up to emails always took place within 48 hours of the initial email being received. This helped to support trust, coordination and co-innovation as ideas evolved. |

There is a possibility that additional questions could have provided additional insight into valuable areas of collaboration that were not otherwise considered in this project. We argue that even though CPD principles were integrated throughout the project cycle, collaboration could always be improved and deepened. There must be constant reflection on how additional collaborative measures can be put in place, whilst also considering how efficiency and project goals can still be effectively achieved according to the desired timeline. In this way, the mathematical models used within Game Theory would be a valuable next level of analysis where cost/benefit of collaboration within educational PPPs can be assessed.

Discussion and conclusion

In this paper we have outlined how CPD and conversation theories can be used to support and reflect on the validity of international PPPs. We have highlighted that there is a lack of research literature pertaining to collaboration strategies for development projects funded by third party groups but carried out by local stakeholder groups in collaboration with international experts. As these collaborations become more common, we seek to contribute to this literature by considering a case study of a transnational PPP, where we used a conceptual CPD model. This model comprises of four dimensions – trust, coordination, co-learning and co-innovation (Arsenyan, & Buyukozkan, 2014) and promotes effective collaboration principles for project managers wishing to foster effective, ethical and valid international partnerships.

To explain the validity of these CPD principles, we also looked to conversation theory, which is itself underpinned by an ethnomethodological perspective. According to this perspective, effective communication takes epistemic status into account, which means that the participants engage in moment-by-moment expressions of understandings with epistemic imbalance driving the interaction (Heritage, 2012a, p. 32) . All parties should be seen as experts on certain areas of knowledge and skills, and the achievement of the high-level shared goals of a development rely on the micro level interactions that help participants to ‘live the macro level goals’ of the project.

We argue that by applying CPD theory to the process of international curriculum review, valuable insights can be gained into how valid and ethical collaboration can be fostered. CPD is implicitly reflexive. Moreover, being collaborative is not just a group of individuals sharing or contributing. The interactions must involve the dimensions of authentic trust, the coordination of common goals, co-learning and co-innovation in order for authentic and valid collaboration to be fostered.

We argue that the above case study serves as an initial entry point into a wider consideration of the value of incorporating CPD principles into international education projects. Incorporating elements of CPD can increase the level of reflexivity that occurs within these collaborations and can support the validity of the processes that are applied. CPD stresses the importance of incorporating active listening, respect and the acknowledgement of expertise among all partners. CPD also highlights that this collaboration is an ongoing process rather than a set of boxes that must be ticked. Brinberg and McGrath (1985) remind us that “validity is not a commodity that can be purchased with techniques… Rather, validity is like integrity, character, and quality, to be assessed relative to purposes and circumstances” (1985, p. 13).

Some level of consultation and collaboration is vital for any successful national curriculum review. This is more difficult to achieve with international curriculum partnerships, however it is even more vital for ensuring the review process is done in an ethical and valid way. Our exploration of these dimensions of CPD show how interrelated they are. This point reiterates that the development of valid communication is a holistic process, with the conditions of CPD helping participants to overcome particular barriers to authentic and equitable interaction, such as physical and temporal distance and cultural insensitivity.

Although international PPPs have their challenges, they offer a range of benefits to all parties involved and can also lead to benefits within the wider educational jurisdiction. For example, PPPs enable a sharing of expertise, perspectives, skills and knowledge that would not be gathered to the same level of deep understanding if the partnerships did not take place. These insights and shared knowledge can then be shared within each partner’s wider network leading to deeper understandings, sensitivities and awareness of different approaches to education, thus decreasing the dominance of post-colonial approaches.

There are several areas worthy of further research based on the findings of this article. Firstly, further insights must be gained regarding how ethical reflexivity is currently being conducted in the field of ESI. As this is a transnational field, there are questions regarding where and how ethical considerations are upheld. In addition, it would be valuable to apply the method of discourse analysis to PPP exchanges and to investigate how the principles of conversation theory can provide insight into how collaboration is fostered or stifled.

References

- Anwaruddin, S. M. (2014). Educational Neo-colonialism and the World Bank: A Rancièrean Reading. In Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies (JCEPS), 12(2).

- Arsenyan, J., & Büyüközkan, G. (2014). Modelling collaborative product development using axiomatic design principles: application to software industry. In Production Planning & Control, 25(7), pp. 515-547.

- Arsenyan, J., Büyüközkan, G., & Feyzioğlu, O. (2015). Modelling collaboration formation with a game theory approach. In Expert Systems with Applications, 42(4), pp. 2073-2085.

- Ball, S. J. (2007). Globalised, Commodified and Privatised: current international trends in education and education policy. In Der Öffentliche Sektor – The Public Sector, Jg, 33, pp. 33-40.

- Barber, M., & Mourshed, M. (2007). How the world’s best-performing school systems come out on top. London: McKinsey & Co. URL: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/social-sector/our-insights/how-the-worlds-best-performing-school-systems-come-out-on-top

- Barber, M., Mourshed, M. & Chijioke, C. (2010). How the world’s most improved school systems keep getting better. URL: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/social-sector/our-insights/how-the-worlds-most-improved-school-systems-keep-getting-better

- Bhaskaran, S. R., & Krishnan, V. (2009). Effort, revenue, and cost sharing mechanisms for collaborative new product development. In Management Science, 55(7), pp. 1152-1169.

- Boreham, N. (2004). A theory of collective competence: Challenging the neo-liberal individualisation of performance at work. In British Journal of Educational Studies, 52(1), pp. 5-17.

- Bower, M. (2008). Affordance analysis – matching learning tasks with learning technologies. In Educational Media International, 45(1), pp. 3–15. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/09523980701847115

- Brennan, S. E. (1998). The Grounding Problem in Conversations With and Through Computers. In S. R. Fussell, & R. J. Kreuz (Eds.). Social and cognitive psychological approaches to interpersonal communication, pp. 201–225. URL: http://www.psychology.stonybrook.edu/sbrennan-/papers/brenfuss.pdf

- Briggs, C. L. (2007). Curriculum collaboration: A key to continuous program renewal. In The Journal of Higher Education, 78(6), pp. 676-711.

- Brinberg, D., & McGrath, J. E. (1985). Validity and the research process. London: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Brock-Utne, B. (2012). Language and inequality: Global challenges to education. In Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 42(5), pp. 773-793.

- Burns, T., & Schuller, T. (2007). The evidence agenda. In Evidence in education: Linking research and policy, pp. 15-32.

- Camarinha-Matos, L. M., & Abreu, A. (2007). Performance indicators for collaborative networks based on collaboration benefits. In Production planning and control, 18(7), pp. 592-609.

- Cambridge University Press & Cambridge Assessment (2019). The Learning Passport: Research and Recommendations Report. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press & Cambridge Assessment.

- Chisholm, L. (2015). Curriculum transition in Germany and South Africa: 1990–2010. In Comparative Education, 51(3), pp. 401-418.

- Chisholm, L. (2005). The making of South Africa’s national curriculum statement. In Journal of Curriculum Studies, 37(2), pp. 193-208.

- Condon, S. L., & Čech, C. G. (2010). Discourse Management in Three Modalities. Language@Internet, 7(6). URL: http://www.languageatinternet.org/articles/2010/2770

- Cooren, F., Kuhn, T., Cornelissen, J. P., & Clark, T. (2011). Communication, Organizing and Organization: An Overview and Introduction to the Special Issue. In Organization Studies, 32(9), pp. 1149–1170. URL: https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840611410836

- Daft, R. L., & Lengel, R. H. (1986). Organizational Information Requirements, Media Richness and Structural Design. In Management Science, 32(5), pp. 554–571.

- Dale, R., & Robertson, S. L. (2002). The varying effects of regional organisations as subjects of globalization of education. In Comparative Education Review, 46(1), pp. 10–36.

- de Bruyckere, P. (2013). So you want to compare educational systems from different countries? Where to start? In From experience to meaning. URL: https://theeconomyofmeaning.com/2013/11/01/so-you-want-to-compare-educational-systems-from-different-countries-where-to-start/

- Dennis, A. R., Fuller, R. M., & Valacich, J. S. (2008). Media, Tasks, and Communication Processes: A Theory of Media Synchronicity. MIS Q., 32(3), pp. 575–600.

- Elliott, G. (2014). Method in our madness? The advantages and limitations of mapping other jurisdictions’ educational policy and practice. In Research Matters: A Cambridge Assessment Publication, 17, pp. 24–29.

- Gaver, W. W., Sellen, A., Heath, C., & Luff, P. (1993). One is not enough: multiple views in a media space. In Proceedings of the INTERACT ’93 and CHI ’93 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 335–341. URL: https://doi.org/10.1145/169059.169268

- Goffman, E. (1961). Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. New York: Random House.

- Goffman, E. (1963). Behavior in Public Places. New York: The Free Press.

- Goodson, I. F. (2003). Professional knowledge, professional lives. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Goyal, S., & Joshi, S. (2003). Networks of collaboration in oligopoly. Games and Economic behavior, 43(1), pp. 57-85.

- Greatorex, J., Rushton, N., Coleman, T., Darlington, E., & Elliott, G. (2019). Towards a method for comparing curricula. URL: https://www.cambridgeassessment.org.uk/Images/549208-towards-a-method-for-comparing-curricula.pdf

- Haider, G. (2016). Process of Curriculum Development in Pakistan. In International Journal of New Trends in Arts, Sports & Science Education (IJTASE), 5(2).

- Heritage, J. (2001). Goffman, Garfinkel and Conversation Analysis. In M. Wetherell, S. Taylor, & S. Yates (Eds.), Discourse theory and practice: a reader. London: SAGE. pp. 47–56.

- Heritage, J. (2012a). Epistemics in action: Action formation and territories of knowledge. In Research on Language & Social Interaction, 45(1), pp. 1-29.

- Heritage, J. (2012b). The Epistemic Engine: Sequence Organization and Territories of Knowledge. In Research on Language and Social Interaction, 45(1), pp. 30–52. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2012.646685

- Heritage, J. (2013). 18 Epistemics in Conversation. In J. Sidnell & Stivers, T. (Eds.) The handbook of conversation analysis. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 370-394.

- Honeycutt, L. (2001). Comparing E-Mail and Synchronous Conferencing in Online Peer Response. In Written Communication, 18(1), pp. 26–60. URL: https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088301018001002

- Hussain, A., Dogar, A. H., Azeem, M., & Shakoor, A. (2011). Evaluation of curriculum development process. In International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 1(14), pp. 263-271.

- Joiner, R., & Jones, S. (2003). The effects of communication medium on argumentation and the development of critical thinking. In International Journal of Educational Research, 39(8), pp. 861–871. URL: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2004.11.008

- Krishna, V., & Morgan, J. (2004). The art of conversation: eliciting information from experts through multi-stage communication. In Journal of Economic Theory, 117(2), pp. 147-179.

- Lamming, R. (1993). Beyond Partnership: Strategies for Innovation and Lean Supply. London: Prentice Hall.

- Lemley, D., Sudweeks, R., Howell, S., Laws, R. D., & Sawyer, O. (2007). The Effects of Immediate and Delayed Feedback on Secondary Distance Learners. In Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 8(3), pp. 251–260.

- Levin, B. (2008). How to change 5000 schools: A practical and positive approach for leading change at every level. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

- Littleton, K., & Mercer, N. (2013). Interthinking: putting talk to work. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Machingambi, S. (2014). The impact of globalisation on higher education: A Marxist critique. In Journal of Sociology and Social Anthropology, 5(2), pp. 207-215.

- Martins, L. L., Gilson, L. L., & Maynard, M. T. (2004). Virtual Teams: What Do We Know and Where Do We Go from Here? In Journal of Management, 30(6), pp. 805–835. URL: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jm.2004.05.002

- Mercer, N. (2000). Words and Minds: How We Use Language to Think Together and Get Things Done. London: Routledge.

- Morgan, S. J., & Symon, G. (2002). Computer-Mediated Communication and Remote Management: Integration or Isolation? In Social Science Computer Review, 20(3), pp. 302–311. URL: https://doi.org/10.1177/089443930202000307

- Paraskeva, J. M. (2018). Curriculum epistemicide: Towards an itinerant curriculum theory. London: Routledge.

- Priestley, M. (2005). Making the most of the Curriculum Review: Some reflections on supporting and sustaining change in schools. In Scottish Educational Review, 37(1), pp. 29-38.

- Priestley, M., & Humes, W. (2010). The development of Scotland’s Curriculum for Excellence: amnesia and déjà vu. In Oxford Review of Education, 36(3), 345-361.

- Rahman, M. I. U., & Missingham, B. (2018). Education in Emergencies: Examining an Alternative Endeavour in Bangladesh. In Engaging in Educational Research. Singapore: Springer, pp. 65-87.

- Reid, A. (2005). Rethinking national curriculum collaboration: Towards an Australian curriculum. Canberra: Department of Education, Science and Training.

- Robertson, S. L., Mundy, K., Verger, A., & Menashy, F. (2012). An introduction to public private partnerships and education governance. In Public private partnerships in education: New actors and modes of governance in a globalizing world, pp. 1-17.

- Schmidt, W. H. (2004). A Vision for Mathematics. In Educational Leadership, 61(5), p. 6.

- Star, S. L., & Griesemer, J. R. (1989). Institutional Ecology, ‘Translation’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals on Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-39. In Social Studies of Science, 19(3), pp. 387–420.

- Stenhouse, L. (1975). An introduction to curriculum research and development. London: Heinemann.

- Taole, M. J. (2013). Teachers’ conceptions of the curriculum review process. In International Journal of Educational Sciences, 5(1), pp. 39-46.

- Trevino, L. K., Lengel, R. H., & Daft, R. L. (1987). Media Symbolism, Media Richness, and Media Choice in Organizations A Symbolic Interactionist Perspective. In Communication Research, 14(5), 553–574. URL: https://doi.org/10.1177/009365087014005006

- UNESCO-IBE. (2013). Training Tools for Curriculum Development: A Resource Pack (Text No. UNESCO/IBE/2013/OP/CD/01; p. 210). URL: http://www.ibe.unesco.org/en/document/training-tools-curriculum-development-resource-pack

- UNESCO-IBE (2017). Developing and Implementing Curriculum Frameworks (No. IBE/2017/OP/CD/02; p. 48. URL: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0025/002500/250052e.pdf

- Verger, A., Lubienski, C., & Steiner-Khamsi, G. (2016). The emergence and structuring of the global education industry: Towards an analytical framework. In World Yearbook of Education 2016. London: Routledge, pp. 23-44.

- Willis, K. S., Chorianopoulos, K., Struppek, M., & Roussos, G. (Eds.) (2010). Shared Encounters. Springer-Verlag. URL: http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/1240866.1241101

- Yates, L. (2016). Europe, transnational curriculum movements and comparative curriculum theorizing. In European Educational Research Journal, 15(3), pp. 366–373. URL: https://doi.org/10.1177/147490411664493

About the Authors

Dr. Sinéad Fitzsimons: Researcher, Research Division, Cambridge Assessment, University of Cambridge (UK); e-mail: fitzsimons.sinead@gmail.com

Dr. Martin Johnson: Senior Researcher, Research Division, Cambridge Assessment, University of Cambridge (UK); e-mail: johnson.m2@cambridgeassessment.org.uk