Abstract: The social consequences of the corona pandemic are unequally distributed. Initial studies show that people with a low household income are particularly affected by the consequences of the pandemic, but also families have been faced with massive challenges for coping with everyday life and subjective health due to the lockdown. In our research we can show and concretise the burden dimensions of parents, but also their resources in times of Corona crisis. It becomes clear that mothers in particular are more affected by emotional consequences, their life satisfaction has dropped most, and they have to take over the care and home schooling of their children for the most part. However, some families are benefiting from the crisis in terms of the time resources they are gaining. It is also striking that the family seems to be both- a resource and a source of stress for women during the lockdown.

Key words: pandemic, family, mental stress, subjective health, life satisfaction

摘要 (约瑟芬·耶伦 & 海克·奥尔布雷希特 : 危机中的家长身份:新冠状病毒大流行期间家长的压力潜能和性别差异):新冠状病毒大流行的社会后果被不平等地分配着。初步的一些研究表明,家庭收入较低的人群尤其受到新冠状病毒大流行的影响,但是由于封锁,家庭在应对日常生活和主观健康方面也面临着巨大的挑战。在我们的研究中可以展示出并具体化家长们的负担维度,以及在新冠状病毒危机时期他们的一些资源。很明显的是母亲更容易受到情感后果的影响,其生活满意度下降的幅度最大,并且她们必须承担起大部分的对其子女的照料和家庭教育工作。然而,一些家庭在获得时间资源方面正在从危机中受益。值得注意的是,家庭在封锁时期似乎既是妇女们的一项资源又是其压力的一个来源。

关键词:大流行,家庭,精神压力,主观健康,生活满意度

摘要 (約瑟芬·耶倫 & 海克·奧爾布雷希特 : 危機中的家長身份:新冠狀病毒大流行期間家長的壓力潛能和性別差異): 新冠狀病毒大流行的社會後果被不平等地分配著。初步的一些研究表明,家庭收入較低的人群尤其受到新冠狀病毒大流行的影響,但是由於封鎖,家庭在應對日常生活和主觀健康方面也面臨著巨大的挑戰。在我們的研究中可以展示出並具體化家長們的負擔維度,以及在新冠狀病毒危機時期他們的一些資源。很明顯的是母親更容易受到情感後果的影響,其生活滿意度下降的幅度最大,並且她們必須承擔起大部分的對其子女的照料和家庭教育工作。然而,一些家庭在獲得時間資源方面正在從危機中受益。值得注意的是,家庭在封鎖時期似乎既是婦女們的一項資源又是其壓力的一個來源。

關鍵詞:大流行,家庭,精神壓力,主觀健康,生活滿意度

Zusammenfassung (Josephine Jellen & Heike Ohlbrecht: Elternschaft in der Krise: Stresspotenziale und Geschlechterunter-schiede der Eltern während der Corona Pandemie): Die sozialen Folgen der Corona Pandemie sind ungleich verteilt. Erste Studien zeigen, dass Menschen mit niedrigem Haushaltseinkommen von den Folgen der Pandemie besonders betroffen sind, aber auch Familien sind durch den Lockdown mit massiven Herausforderungen hinsichtlich der Alltagsbewältigung und der subjektiven Gesundheit konfrontiert. In unserer Forschung können wir die Belastungsdimensionen der Eltern, aber auch ihre Ressourcen in Zeiten der Corona-Krise aufzeigen und konkretisieren. Es wird deutlich, dass vor allem Mütter stärker von den emotionalen Folgen betroffen sind, ihre Lebenszufriedenheit am stärksten gesunken ist und sie die Betreuung und Beschulung ihrer Kinder weitgehend übernehmen müssen. Einige Familien profitieren jedoch von der Krise in Bezug auf die Zeitressourcen, die sie gewinnen. Auffallend ist auch, dass die Familie sowohl Ressource als auch Belastungsfaktor für Frauen während des Lockdown zu sein scheint.

Schlüsselwörter: Pandemie, Familie, psychische Belastung, subjektive Gesundheit, Lebenszufriedenheit

Резюме (Джозефине Йеллен & Хайке Ольбрехт: Социальная группа «Родители» в период пандемии: Стрессовые сценарии и гендерные особенности поведения в условиях «новой нормальности»): Социальные последствия пандемии распределяются неравномерно. Первые исследования показывают, что в наибольшей степени пандемия затронула людей с низким уровнем дохода. Семьи как социальная группа также ощущают на себе последствия локдауна и сталкиваются с мощнейшими вызовами как в плане охраны своего здоровья, так и адаптации к новым условиям жизни. В данной статье будут рассмотрены и конкретизированы сегменты «новой» нагрузки, которая ложится на плечи родителей. В то же время будут обозначены ресурсы, которые «поставляет» новая коронавирусная ситуация. По результатам исследования становится очевидным, что прежде всего эмоциональных последствий такой перестройки страдают женщины; именно у них отмечается резкое снижение удовлетворенностью жизнью; в большинстве случаев как раз женщины берут на себя заботу по воспитанию и обучению детей в период пандемии. С другой стороны, некоторые семьи извлекают выгоду из новых условий, в частности, в плане высвобождающихся временных ресурсов, которые затем могут быть с пользой освоены. Отметим то, что проходит красной нитью через все исследование: в период локдауна семья представляется женщине скорее амбивалентной структурой: в ней она видит и ресурс, и то, что провоцирует стрессовые состояния.

Ключевые слова: пандемия, семья, психическая нагрузка, здоровье личности, удовлетворенность жизнью

The Corona pandemic as a social challenge

The corona pandemic is changing public and private life to an unprecedented extent. New insecurities and challenges are showing themselves with particular intensity: Reduced contact with friends and family, but also work in the home office and child care have changed everyday life considerably and, last but not least, have had an impact on well-being. Families and parents in particular were faced with special challenges during the lockdown period: for example, gainful employment had to be guaranteed in the home office parallel to home schooling or childcare, regular arrangements for childcare, for example by supporting grandparents, were difficult to implement, as were everyday leisure activities. Extensive contact restrictions had a massive impact on everyday life, not only were the childcare institutions (schools and kindergartens, day nurseries) closed, but public places (playgrounds etc.) had to be avoided and personal contact with people outside the home was no longer possible.

In view of this scenario, we assume that the period of the Corona-related lockdown and its consequences, such as the closure of schools or the greatly reduced contact with friends and family, have an impact on the subjective, psychosocial health of individuals. Parents and families are exposed to particular stress potentials.

In order to investigate how the lockdown in the aftermath of the corona pandemic has affected health and coping with everyday life, an online survey was carried out to identify special social challenges and stress dimensions in times of the corona pandemic in the short term, to learn more about the consequences of social distancing and the groups particularly affected by the measures to contain the pandemic. Along our study we identify various differences in the intensity of the pressure: in particular people with low educational capital, women, but also parents are affected by the social consequences of the corona pandemic.

Research status

More than 10 million children and young people were affected by the closure of day-care centres and schools during the lockdown in Germany. This not only affected the children or pupils, but also their parents, who were confronted with unprecedented challenges in schooling and child care (Bujard et al., 2020). According to Allmendinger et al. (2020), mothers in particular were affected by the increasing care tasks and significantly reduced their working hours in the course of the corona pandemic and emerged as losers from the corona crisis.

Studies are currently proving that there is an intensification of gender-specific differences as a result of the corona pandemic: Differences between men and women with regard to financial worries and burdens, as well as differences in salary losses, make it clear that women are not only increasingly bearing the burden of childcare (Blom et al., 2020), they are also affected by salary losses and once again exposed to a double burden (Hövermann, 2020). Almost 93 percent of all parents now look after their children at home themselves. Grandparent care has decreased from 8.3 percent before the Corona crisis to 1.4 percent. In the household, in half of the cases the woman alone takes over childcare. The corona crisis therefore has the potential to increase gender inequality in the labour market if more and more short-time work and redundancies are implemented in sectors with a high share of women, such as the hotel and restaurant industry (Blom et al., 2020).

In the wake of the corona pandemic, it is mostly mothers who adjust their working hours to childcare (Bünning et al., 2020). Minor additional burdens due to home schooling can be seen in the case of mothers, working parents and parents with several children to be cared for or parents with higher education qualifications (Porsch & Porsch, 2020).

However, there are also counter findings to the currently much discussed thesis of the re-traditionalisation of gender roles: Bujard et al. (2020), for example, do not confirm that the traditionally divided gender roles have revived during the pandemic, they state that the participation of fathers in housework has even increased (ibid.).

Method and Sample

In order to focus on the social pressure of the corona pandemic, a partially standardised online survey was carried out, in which the topics of health, pressure, life satisfaction, information management and trust, solidarity and socio-demographic data were asked. We focussed on the subjective self-assessment of the participants, who were asked at one point of the survey about their perception before and during the pandemic. The questionnaire used comprised 55 questionnaire batteries and 4 open questions and was available from 14 April to 03 May 2020, i.e. during the relevant period of the lockdown in Germany.

The survey was advertised via print media such as daily newspapers, homepages, social networks, word of mouth influence and email distribution lists. Accordingly, it is a convenience sample, which is subject to certain limitations: we do not receive representative data, the results are not to be generalised, but rather represent a mood picture of our sample from this particular phase. Although the sampling strategy does not allow us to determine a statistical population, we can state that there are 2797 hits on the questionnaire. After data cleansing, 2,009 data sets were included in the evaluation.

The sample produced is not a representative cross-section of the demographic, but a positive selection: the majority of participants in the survey were younger, working people with high cultural capital. Women (71%) participated significantly more often than men (28%). 31% of respondents live with children under 18 in the household. Almost two thirds of the participants are under 40 and one third of the respondents are over 40. The majority of respondents were born in Germany (94.5%) and live in the German federal state of Saxony-Anhalt (46.6%).

With regard to the highest school-leaving certificate, it is clear that the sample has a high education capital. 82.4% of the respondents have acquired the A-levels or the entrance qualification for Universities of applied sciences. The majority (79.2%) of those surveyed are in gainful employment, whereas 20.8% are not employed. One third of the participants in the study suffer from a chronic illness or have a recognised disability.

Sample selection needs to be appropriately framed in light of the results, especially when it comes to quantitative health research: for example, the Healthy user bias (see e.g. Shrank et al., 2011) states that healthier people are the main respondents to health or illness surveys. Generalising the results to the potentially less healthy population can therefore be problematic. Nevertheless, it is possible on the basis of the study results to gain a first impression of how the situation of corona-induced non-contact is inscribed in the everyday life of the respondents. Entirely in line with classical social research, we ask ourselves the question of what exactly happens in the everyday life of the actors or how Erving Goffman formulated this question: “What the hell is going on here? (Goffman, 1974, p. 17).

Results

Subjective health and well-being

However, it is noticeable that feelings such as stress and exhaustion during the lockdown were significantly reduced in the sample: The proportion of respondents who experienced stress sometimes to very often before the corona crisis fell by 15.5% during the pandemic. Similarly, the proportion of those who are sometimes and (very) often exhausted decreased by 12.1% during the pandemic. On the other hand, respondents felt lonely twice as often as before the pandemic. The subjective feeling of security has also decreased by a quarter and the feeling of fear has doubled compared to before and during the pandemic. But also the general life satisfaction has decreased clearly compared to before and during the pandemic. Before the pandemic, 81.2% confirmed that they were satisfied or very satisfied with their lives, whereas general life satisfaction during the pandemic fell by 21.6% to 59.6%. A difference in response behaviour between men and women is only marginally discernible; however, the data show a difference along the educational level.

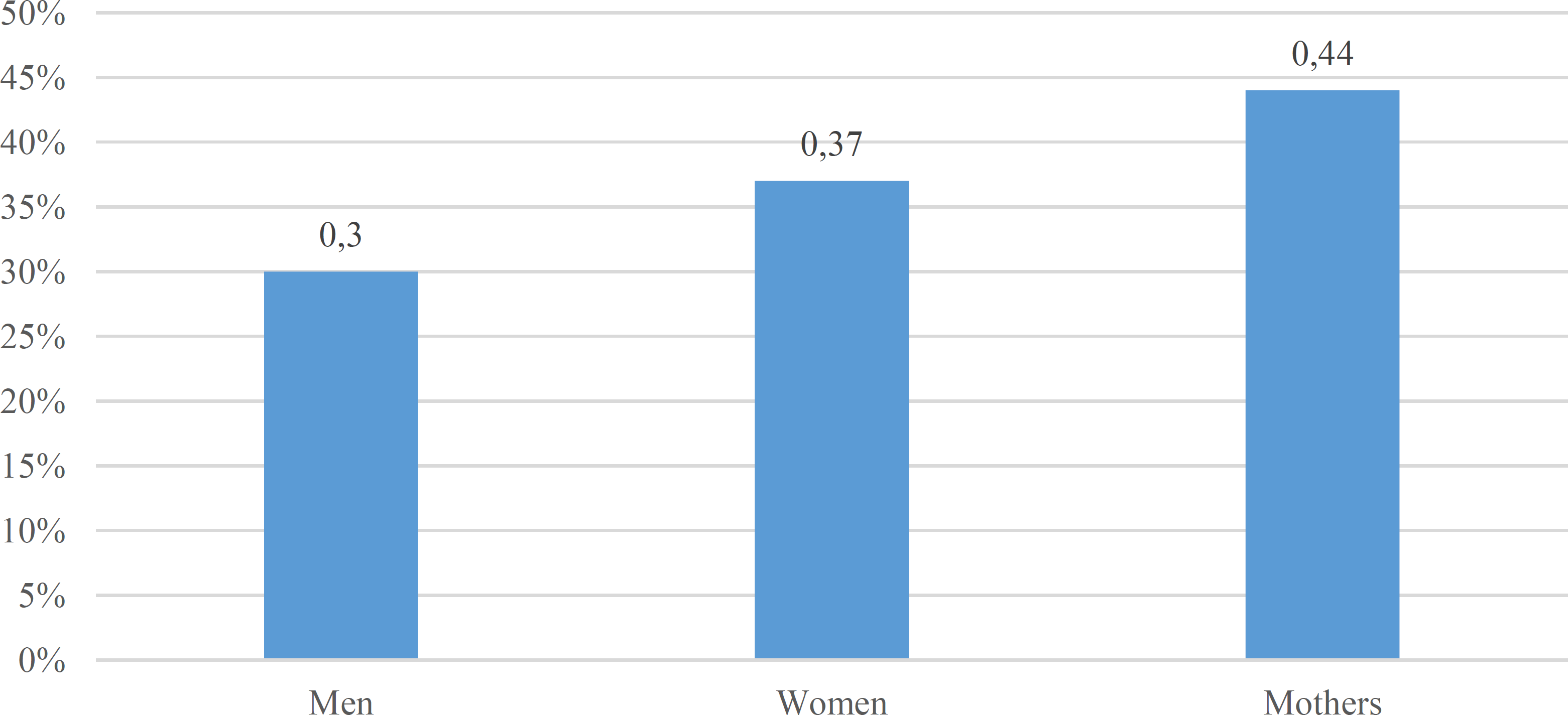

Question: When you look back on the lockdown period so far, how much of a emotional pressure do you feel?

Reply formats: 1) never 2) rarely 3) sometimes 4) often 5) very often

Only categories 4 and 5 are shown in the figure and have been condensed.

It is noticeable, however, that feelings such as stress and exhaustion were significantly reduced in the sample during the period of lockdown: The proportion of respondents who experienced stress sometimes to very often before the corona crisis fell by 15.5% during the pandemic. Similarly, the proportion of those who are sometimes and (very) often exhausted decreased by 12.1% during the pandemic. However, respondents felt lonely twice as often as before the pandemic. The subjective feeling of security has also decreased by a quarter and the feeling of fear has doubled compared to before and during the pandemic. But also the general life satisfaction has decreased significantly compared to before and during the pandemic. Before the pandemic, 81.2% confirmed that they were satisfied or very satisfied with their lives, whereas general life satisfaction during the pandemic fell by 21.6% to 59.6%. A difference in response behaviour between men and women is only marginally discernible; however, the data show a difference along the educational level.

Parenthood and Corona

In our sample, 30.6% (n=615) of the participants affirmed that they live in a household with at least one child under 18 years of age. Based on a concept of family that goes beyond biological relationships, we refer to this group of people as parents in the following. We have decided to ask about the children under 18 years of age in the household (Family Households, Burkart 2008), as we assume that care and homeschooling arrangements are particularly intensive/challenging in this case.

More than two thirds of the parents surveyed had to take over the care of their underage children themselves after the day-care and school closures, half of them worked in the home office during this time. The majority of the mothers provided 73% of the care and 39% of the children’s home schooling, whereas the fathers stated that they provided 51.5% and 13% of the children’s care and home schooling respectively.

The majority of parents felt restricted in everyday life (72%), in pursuing hobbies (72%), in maintaining social and friendly relationships (92%), in contact with the family (86%), in voluntary or political work (52%) and 47% in their professional activities. The fact that women felt more restricted to a large extent – especially in terms of gainful employment, hobbies, friendships and everyday activities – again highlights a gender-specific difference.

30% of mothers in our sample stated that they needed more support at home during the lockdown period, whereas only 14% of fathers identified an increased need for support. However, only 16% of mothers and 9% of fathers experience more support than before the pandemic.

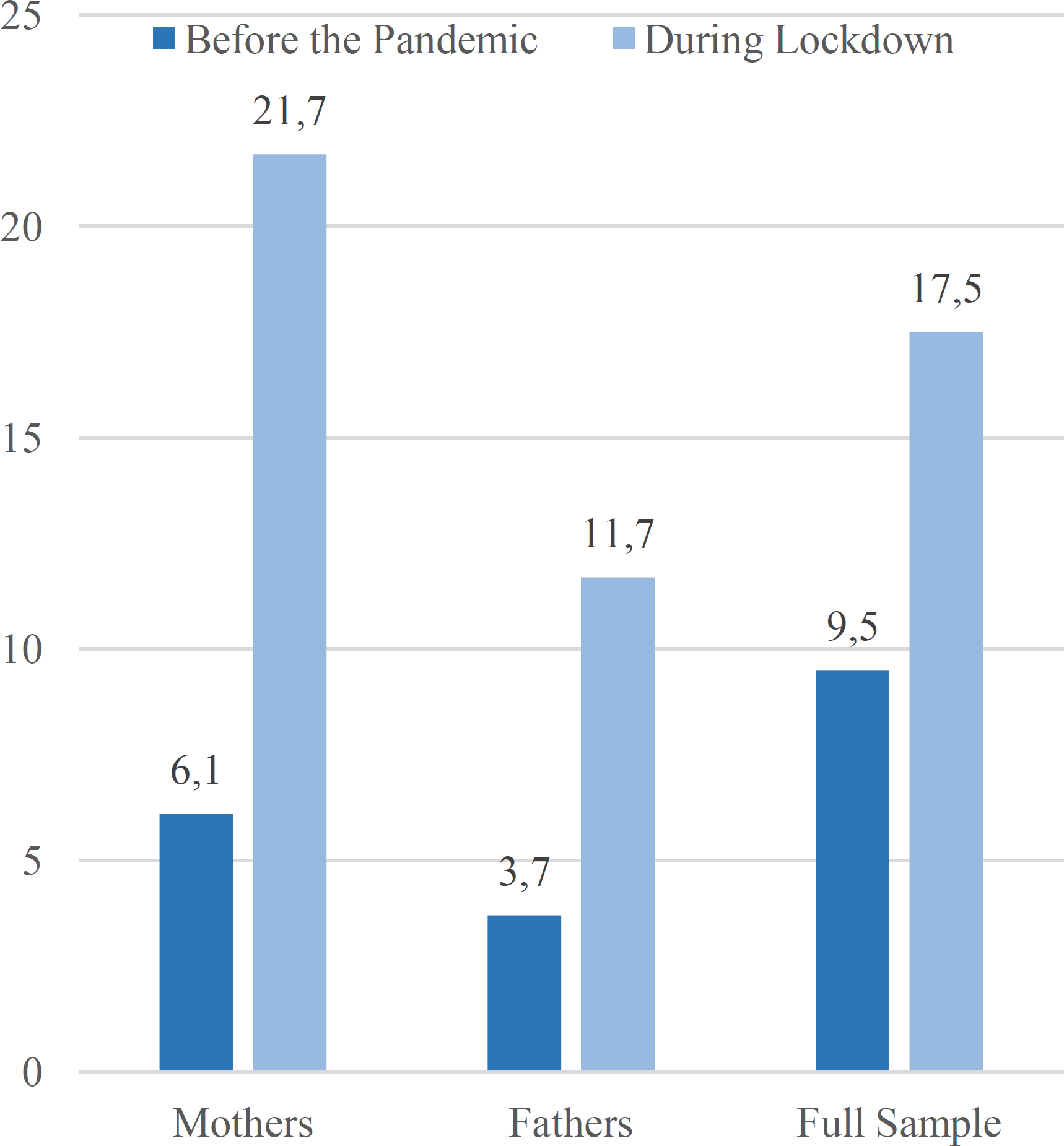

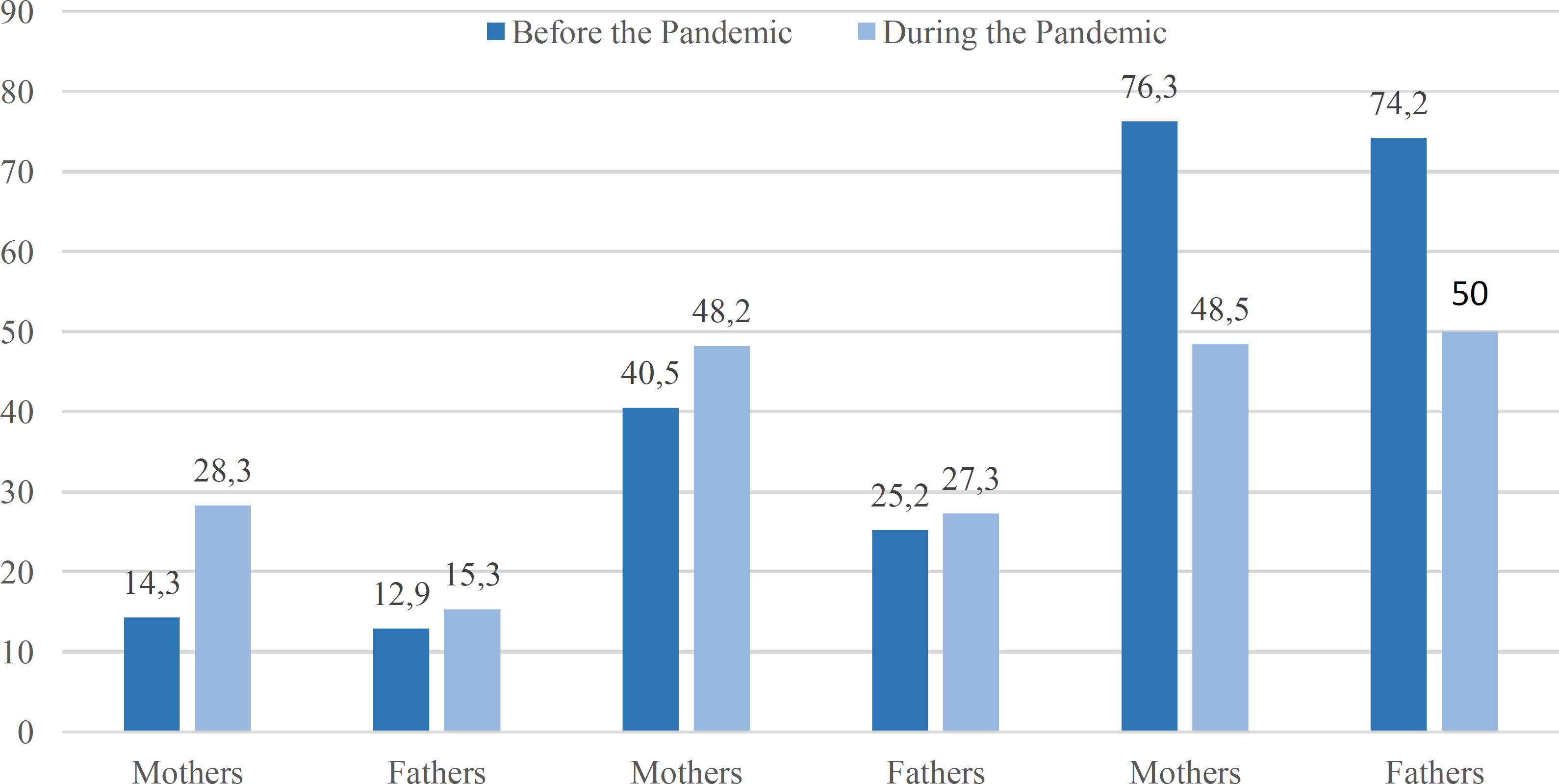

Clear differences between mothers and fathers and between the general sample and the group of parents can be seen in many areas, such as in the emotions sampled before and during the pandemic or during the lockdown. The positive effects of the corona pandemic mentioned above, such as reduced feelings of exhaustion and stress, cannot be established for the parents’ group. On the contrary, we see an increase of 8 and 3% respectively in the feeling of exhaustion and stress, especially among mothers. Among fathers, an increase of 2 and 3% respectively can be observed. Similar findings can be seen for nervousness (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Comparison of feelings of nervousness, exhaustion and security between fathers and mothers (from left to right), grouped, Percentage figures

Questions: How often did you experience the following feelings before the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic? (dark blue) How often did you experience the following feelings after the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic? (light blue);Reply formats: 1) never 2) rarely 3) sometimes 4) often 5) very often

Only categories 4 and 5 are shown in the figure and have been condensed.

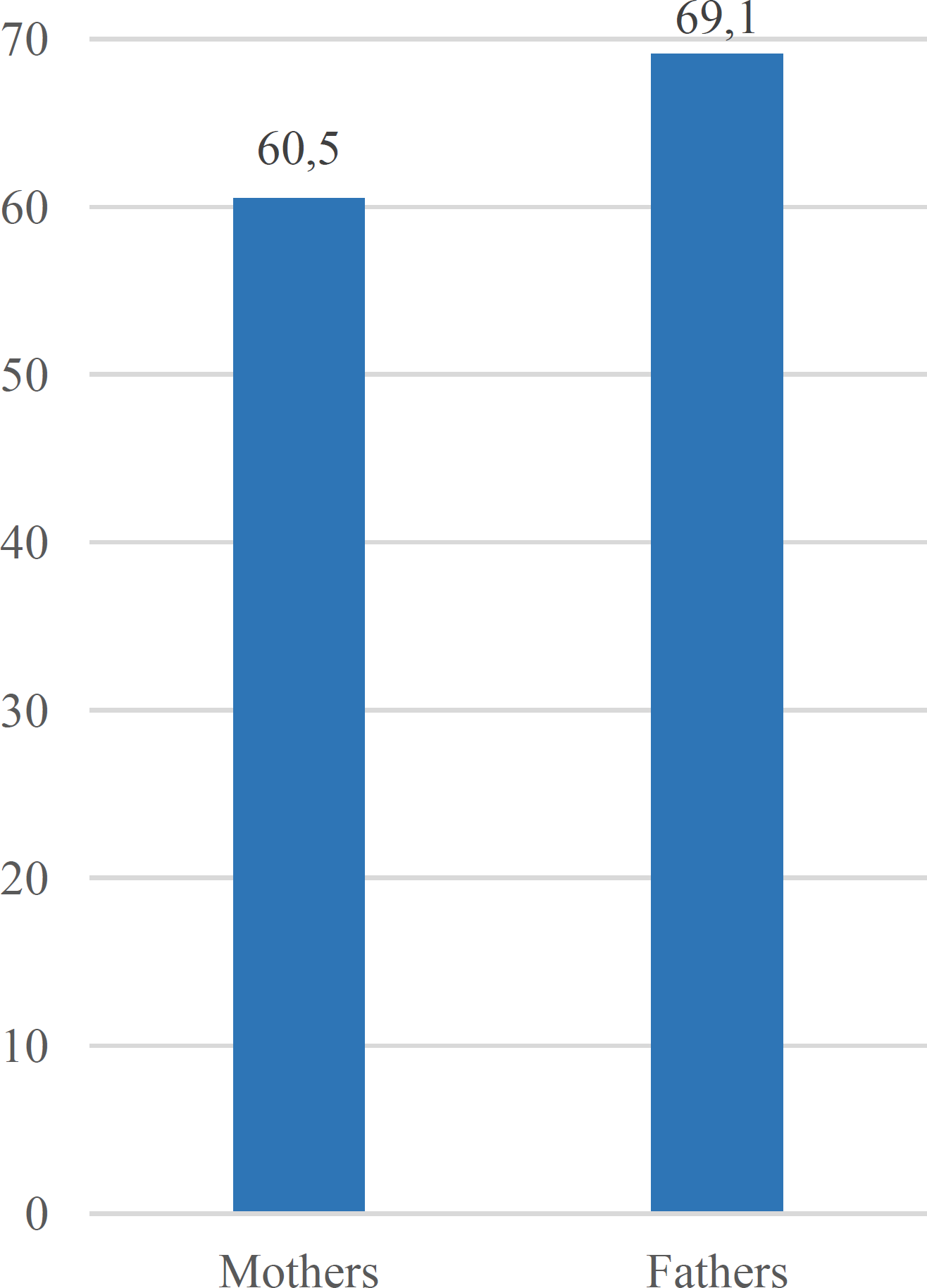

Although there was a sharp increase in anxiety feelings for the whole sample (the feeling of anxiety doubled), in the parents’ group the feelings of anxiety more than tripled (see Figure 3). Existential anxiety also occurred more frequently among parents, but more often among women than among men, so that the ratio before Corona has been reversed: Whereas before the pandemic fathers were more concerned about their livelihoods, mothers were more so during the lockdown.A similar finding can be made for the feeling of nervousness: if the perception of this feeling in the general sample increases by about 5% during the pandemic, the number of mothers who feel nervous during the pandemic (during the lockdown) doubles. The increase in nervousness among fathers compared to before and during the pandemic is only just under 3%. Mothers (13%) are more likely to feel sadness before the pandemic than fathers (4%), increasing by 10% and 6% respectively during the lockdown period. However, there are hardly any differences to the overall sample – the same applies to the feeling of loneliness, security and satisfaction. With regard to general life satisfaction, a clear drop can also be seen in the parents’ group, although here too there are differences between mothers and fathers: the life satisfaction of mothers during the pandemic falls by almost 10% more than that of fathers (see Figure 4).

Questions: How often did you experience the following feelings before the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic? (dark blue) How often did you experience the following feelings after the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic? (light blue);Reply formats: 1) never 2) rarely 3) sometimes 4) often 5) very often

Only categories 4 and 5 are shown in the figure and have been condensed.

Question: How satisfied are you currently with your life in general?

Reply formats: 1) very unsatisfied 2) unsatisfied 3) moderate 4) satisfied 5) very satisfied 6) not specified

Only categories 4 and 5 are shown in the figure and have been condensed.

On the other hand, the feeling of happiness contrasts with the general trends in emotions in the comparison between parents and the general sample before and during the pandemic: thus mothers in particular are happier before the pandemic than childless women, and even during the lockdown period it is apparent that the feeling of happiness, while decreasing, is still somewhat more pronounced than in the overall sample. However, it is also shown that the loss in the quantity of the feeling of happiness, with a decrease of 20%, is much more serious for mothers than for fathers.

Resources and resilience in the crisis

Our study focused not only on the subjective perception of health and stress and the everyday coping of individuals, but also on questions about resilience factors and positive experiences in the course of the pandemic, which were collected via open questions.

To this end, three open questions were asked in the survey:

- What helps you to get through the pandemic period in a healthy and psychologically stable way?

- When you now look back at the time of the contact ban and the corona pandemic, what has been your burden?

- The third question is preceded by the selection question “Do you personally see something positive in this period? If the answer to this question was ‘yes’, we asked the open question: “Please briefly describe the positive aspects for you”.

The analysis of the open questions about categorisations showed that the family was perceived both as a factor of resilience and as a burden, and that new reflections on the self-world relationship were stimulated by the pandemic and modes of self-care were used as stabilising mechanisms.

For women in our sample, self-care (e.g. through meditation as a form of emotional management) was a frequently pursued strategy for maintaining psychological stability (74% compared to 25% of men).

It is also interesting to note that for women, the family seems to be both a place of stress and resilience: women experienced the family as a far greater dimension of stress (83% compared to 16% of men) and at the same time as a resilience factor (81% compared to 19% of men). The time of the lockdown also brought genuinely positive aspects for the participants – in particular time gains, which some families report, as the time of the lockdown is definitely experienced as a deceleration. As representative family sociology studies of recent years show, families often complain about the feeling of time shortage (BMFSFJ, 2012) and a lack of work-life balance. In light of this, some families feel that the time spent away from contact is a gain in time. These “gifts of time” make it possible to (again) provide quality time together in the families and make questions of work-life balance, the reorganisation of work routines and the organisation of everyday life debatable again and stimulate processes of reflection. People with high educational capital benefit from the time gains and experiences, however, both quantitatively and qualitatively.

Discussion and conclusion

According to our research, there is evidence that parents and especially mothers have experienced emotional, performance and work-related disadvantages during the contact restrictions, which will further advance the debate on structural gender differences, mental load and social inequality. Along the lines of the results presented here, we can agree with the findings to date, which show that parents and especially mothers have been more affected by the social consequences of the pandemic.

As we have shown, compared to our general sample, parents are not affected by the small gains of the corona pandemic, such as the reduction of exhaustion and stress. On the contrary, a slight increase can even be seen here. Positive effects can only be seen for the group of parents who perceived the pandemic period as a short break from the general shortage of time in families and who were able to use it as an opportunity to experience other models of work-life balance. This is more likely to affect parents with high educational capital, who generally also have good financial earning opportunities and are more likely to be offered opportunities to work in the home office and to share the care work for the children between the partners.

The results presented are limited, on the one hand, with regard to the sample structure used, but also with regard to the survey period of the lockdown: our results refer to a period of time which can be described as at least exceptional, and at the same time the question arises as to what long-term social consequences the corona pandemic will have for parents and children.

We want our study to be understood as a first mood picture, which provides insights into the living world of parents during the lockdown. More than 60% of all respondents agreed to a follow-up survey, so that the results of a second survey can clearly show a process. Further qualitative surveys (e.g. interviews) will deepen the descriptive-quantitative data and show whether the corona crisis is inscribed in the collective memory.

References

- Allmendinger, J. (2020): Zurück in alte Rollen. Corona bedroht die Geschlechtergerechtigkeit. [Back into old roles. Corona threatens gender justice] WZB Mitteilungen, Issue 168.

- Blom et al. (2020): Die Mannheimer Corona-Studie: Schwerpunktbericht zu Erwerbstätigkeit und Kinderbetreuung. [The Mannheim Corona Report: Focus on employment and childcare]. URL: https://www.uni-mannheim.de/gip/corona-studie/ (retrieved: 2020, September 01).

- Bujard, M., et al. (2020): Eltern werden in der Corona-Krise. Zur Improvisation gezwungen. [Becoming parents in the Corona crisis. Forced to improvise] Bundesinstitut für Bevölkerungsforschung, Wiesbaden. URL: https://www.waxmann.com/?eID=texte&pdf=4231OpenAccess03.pdf&typ=zusatztext (retrieved: 2020, September 22).

- Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend (BMFSFJ) (2012): Achter Familienbericht – Zeit für Familie. Familienzeitpolitik als Chance einer nachhaltigen Familienpolitik. [Eighth Family Report – Time for Family. Family time policy as an opportunity for a sustainable family policy.] URL: https://www.bmfsfj.de/blob/93196/b8a3571f0b33e9d4152d410c1a7db6ee/8–familienbericht-data.pdf (retrieved: 2020, July 30).

- Bünning, M., Hipp, L., & Munnes, S. (2020): Erwerbsarbeit in Zeiten von Corona, WZB Ergebnisbericht. [Gainful employment in times of Corona, WZB result report.] Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB). URL: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/216101 (retrieved: 2020, September 03).

- Burkart, G. (2008): Familiensoziologie. [Family Sociology]. Konstanz, UTB.

- Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Harvard University Press.

- Hövermann, A. (2020): Soziale Lebenslagen, soziale Ungleichheit und Corona – Auswirkungen für Erwerbstätige. Eine Auswertung der HBS-Erwerbstätigenbefragung im April 2020. [Social situations, social inequality and corona – implications for the working population. An evaluation of the HBS employee survey in April 2020.] Hans-Böckler-Stiftung (Ed.), Policy Brief WSI 6/2020.

- Porsch, R., & Porsch, T. (2020): Fernunterricht als Ausnahmesituation. Befunde der bundesweiten Befragung von Eltern und Kindern in der Grundschule. [Distance learning as an exceptional situation. Findings of the nationwide survey of parents and children at primary school.]. In Die Deutschen Schulen (DDS), supplement 16, pp. 61-78.

- Shrank, W. H., Patrick, A. R., & Brookhart, M.A. (2011): Healthy user and related biases in observational studies of preventive interventions: a primer for physicians. In Journal of General Internal Medicine 2011; 26, pp. 546– 50.

About the Authors

M.A. Josephine Jellen: Otto-von-Guericke-University Magdeburg, Faculty of Human Sciences, Department of Sociology (Germany); e-mail: josephine.jellen@ovgu.de

Prof. Dr. Heike Ohlbrecht: Otto-von-Guericke-University Magdeburg, Faculty of Human Sciences, Department of Sociology (Germany); e-mail: heike.ohlbrecht@ovgu.de