Abstract: The future of arts education is at stake.This paper attempts to examine the future of arts education via the responses of a qualitative survey, student samples, individual interviews, and research regarding arts education as essential education for all learners during a pandemic and beyond. The sudden decree that all attendance at public and private schools would be canceled from mid-March to the end of April, 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and then until the end of the 2020 school year, left students, teachers, parents, and schools in shock. What did this decree mean for the future of arts education? Arts education is defined in Washington State basic education law as an essential academic learning requirement (EALR) since 1993 (Washington State Legislature [WSL], 1993), and currently defined as dance, media arts, music, theatre, and visual arts.

Keywords: artistic processes; arts education; arts teachers; arts integration; future of arts education

摘要 (安妮·约瑟夫:在大流行期间,艺术教育的未来是什么? 目前,它是基本的,虚拟的和混合的!):艺术教育的未来岌岌可危。本文试图通过定性调查,学生样本,个人访谈以及关于在大流行期间及之后对所有学习者进行艺术教育作为基本教育的研究来检验艺术教育的未来。突如其来的法令,即由于新冠状病毒大流行从2020年3月中旬至4月底所有公立和私立学校的课程将被取消,之后延续到2020年学年结束,使得学生,老师,家长和学校均感到震惊。这一法令对于艺术教育的未来意味着什么?自1993年以来,华盛顿州基础教育法就将艺术教育定义为一项基本的学术学习要求(EALR)(华盛顿州立法机关[WSL],1993年),目前将其定义为舞蹈,媒体艺术,音乐,戏剧和视觉艺术。

关键词:艺术过程; 艺术教育; 艺术老师; 艺术融合; 艺术教育的未来

摘要 (安妮·約瑟夫:在大流行期間,藝術教育的未來是什麼? 目前,它是基本的,虛擬的和混合的!)藝術教育的未來岌岌可危。本文試圖通過定性調查,學生樣本,個人訪談以及關於在大流行期間及之後對所有學習者進行藝術教育作為基本教育的研究來檢驗藝術教育的未來。突如其來的法令,即由於新冠狀病毒大流行從2020年3月中旬至4月底所有公立和私立學校的課程將被取消,之後延續到2020年學年結束,使得學生,老師,家長和學校均感到震驚。這一法令對於藝術教育的未來意味著什麼?自1993年以來,華盛頓州基礎教育法就將藝術教育定義為一項基本的學術學習要求(EALR)(華盛頓州立法機關[WSL],1993年),目前將其定義為舞蹈,媒體藝術,音樂,戲劇和視覺藝術。

關鍵詞:藝術過程; 藝術教育; 藝術老師; 藝術融合; 藝術教育的未來

Zusammenfassung (AnnRené Joseph: Was ist die Zukunft der kulturellen Bildung inmitten einer Pandemie? Im Moment ist sie essentiell, virtuell und hybrid!): Die Zukunft der Kunsterziehung steht auf dem Spiel. Dieses Papier versucht, die Zukunft der Kunsterziehung anhand der Antworten einer qualitativen Umfrage, von Schülerstichproben, Einzelinterviews und Forschungsarbeiten zu untersuchen und die Kunsterziehung als wesentliche Bildung für alle Lernenden während einer Pandemie und darüber hinaus zu betrachten. Der plötzliche Erlass, dass aufgrund der COVID-19-Pandemie von Mitte März bis Ende April 2020 und dann bis zum Ende des Schuljahres 2020 der gesamte Besuch öffentlicher und privater Schulen gestrichen werden sollte, versetzte SchülerInnen, LehrerInnen, Eltern und Schulen in Schock. Was bedeutete dieses Dekret für die Zukunft der Kunsterziehung? Kunsterziehung wird im Grundbildungsgesetz des Staates Washington seit 1993 (Washington State Legislature [WSL], 1993) als eine wesentliche akademische Lernvoraussetzung (EALR) definiert und derzeit als Tanz, Medienkunst, Musik, Theater und visuelle Künste definiert.

Schlüsselwörter: künstlerische Prozesse; Kunsterziehung; Kunsterzieher; Kunstlehrer; Kunstintegration; Zukunft der Kunsterziehung

Резюме (АннРене Джозеф: Как выглядит будущее культурного образования на фоне пандемии? Сейчас оно эссенциально, виртуально и гибридно!): Будущее эстетического воспитания поставлено на карту. В настоящей работе предпринимается попытка определить роль эстетического воспитания на основе ответов, полученных путем применения качественных методов исследования, результатов опроса фокус-групп школьников, нарративных интервью, анализа научной литературы. Эстетическое воспитание рассматривается как значимая часть образования для всех типов обучающихся в период пандемии. Внезапное распоряжение властей о закрытии государственных и частных школ из-за пандемии коронавируса с середины марта по конец апреля 2020 года и далее до окончания нового учебного года повергло в шок всех – учеников, учителей, родителей, администрацию учебных заведений. Что означает этот запрет применительно к эстетическому воспитанию, каким видится его будущее в свете последних событий? В основном законе об образовании штата Вашингтон эстетическое воспитание с 1993 года определяется как важная академическая предпосылка для осуществления учебного процесса; в настоящее время в его структуру включены танец, медийное искусство, музыка, театр, визуальные искусства.

Ключевые слова: эстетические процессы, эстетическое воспитание, педагог в области эстетического воспитания, интеграция областей искусства, будущее эстетического воспитания

Introduction

The sudden decree that all attendance at public and private schools would be canceled from mid-March to the end of April, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and then until the end of the 2020 school year left students, teachers, parents, and schools in shock. Education policy, practice, and modes of instruction became virtual across the world. Education became homebound, home-schooling the new norm. What is the future of arts education in the midst of these new ways of teaching and learning? Arts education is and remains essential, and this article will attempt to share what is being done at the local, regional, state, national, and international levels to ensure arts education for all learners—albeit via synchronous and asynchronous distance learning.

The decree that school attendance in most school districts in Washington State will continue to be taught via virtual and remote formats for the start of the 2020-2021 school year remains the norm (Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction [OSPI], n.d., 2020a). School arts projects, presentations, and performances remained and remain unfinished and dismantled—or virtual—for the time being. Technology integration and infusion techniques, skills, platforms, and equipment are now in the forefront. However, professional development for those students, parents, and teachers who are expected to use these new methods is sorely lacking and certainly challenging to implement.

The State Education Agency Directors of Arts Education (SEADAE) and other like-minded national educational and arts organizations, including and not limited to the National Dance Education Organization (NDEO), the National Association for Music Education (NAFME), the Educational Theatre Association (EdTA), and the National Art Education Association (NAEA), collaborated and created a joint statement that provides guidance, support, and vision for keeping arts education essential, and a part of basic education for all learners —involving the subjects of dance, media arts, music, theatre (creative dramatics), and visual arts (National Coalition for Core Arts Standards [NCCAS], 2014). The three key principles espoused in the “Arts Education is Essential” unified statement are:

- “Arts education supports the social and emotional well-being of students, whether through distance learning or in person.”

- “Arts education nurtures the creation of a welcoming school environment where students can express themselves in a safe and positive way.”

- “Arts education is part of a well-rounded education for all students as understood and supported by federal and state policymakers.” (National Association for Music Education [NAfME], 2020; State Education Agency Directors of Arts Education [SEADAE], 2020).

Using “three principles” framework, this paper provides the results of a seven question qualitative survey conducted in the spring of 2020 designed specifically to elicit responses regarding the future of arts education. (Joseph, 2020ai). Included here are direct quotes revealing hopes, plans, and concerns for the future of arts education in real-time, as reported anonymously by 46 respondents during May 2020.

International Symposium Survey Question – What is the Future of Arts Education?

A seven-question qualitative, confidential, and anonymous survey was designed and developed based upon the question “What is the future of arts education?” The query came as an invitation to participate and present at the 14th Annual Symposium: Educational Innovations around the World in the Wake of the COVID-19 Epidemic of 2020, sponsored by Seattle Pacific University (SPU) and the School of Education (SOE). The presentation was entitled: The Future of Arts Education with the essential question being “What is the future of arts education?” (Joseph, 2020b). All seven questions were answered by each of the respondents, N = 46. The data from the pie charts and the survey responses inform the narrative for this article. The survey was distributed through the Washington Art Education Association (WAEA), the statewide visual arts education association, and an affiliate organization to the National Art Education Association (NAEA). The survey was sent out to WAEA board members on May 7, 2020, and to the general membership in the WAEA May eNews, on May 13, 2020, and available for input for 26 days through June 1, 2020. The WAEA co-president also posted the survey link on the WAEA Facebook group site. Emails with the survey link were also sent to the leadership of the Dance Educators Association of Washington (DEAW), Washington Music Educators Association (WMEA), and the Washington State Thespians, and posted on two arts education LinkedIn profiles. Survey responses from dance, music, theatre, visual arts, and media and graphic arts teachers, professors, advocates, parents, and students were submitted. All seven survey questions were answered by all 46 respondents. Two survey questions asked information-seeking responses regarding subject matter and level of instruction, and five survey questions were narrative or constructed responses. A summary of the survey respondent replies, by question, provides a prediction for the future of arts education, at least in the near future. A copy of the qualitative survey is shared as Appendix A (Joseph, 2020a). A PowerPoint about the survey results was shared at the 14th Annual Symposium: Educational Innovations around the World in the Wake of the COVID-19 Epidemic of 2020, sponsored by Seattle Pacific University (SPU) and the School of Education (SOE) (Joseph, 2020b), as well as at the Arts Education Partnership (AEP) Virtual Gathering 2020 (Fortune, Gillett, & Joseph, 2020). Additionally, an article about the survey was featured in the summer issue of the WAEA Splatter Magazine (Joseph, 2020c). Plans to re-administer the survey in fall 2020 are underway to examine further developments in arts education during this time of synchronous and asynchronous virtual and remote learning; and to compare to the spring 2020 survey responses. The survey was vetted by the WAEA leadership for clarity, and in efforts at validity and reliability, prior to sending to the WAEA board and membership.

Respondents to the survey questions were able to write as much as they wanted to write, and all respondents gave permission to share their replies anonymously and without any identifying information. Further, some respondents sent personal emails, student artworks, video recordings of choirs and solo singers, and video recordings of entire school and district culminating performances, art shows, on-line student art galleries, and statewide ‘all arts’ end-of-year-celebrations. All of these actual student samples, representing all five arts disciplines: dance, media arts, music, theatre, and visual arts, illustrate how arts education continued to thrive in the midst of school closures and distance instruction in virtual formats. Live visual and performing arts presentations and performances including spring concerts, presentations, productions, and galleries; as well as ‘end-of-the-year’ events, celebrations, and graduations were cancelled. Some events were re-scheduled—albeit virtually or in hybrid formats. The samples illustrate authentic student engagement in visual arts. The artworks graphically illustrate student social-emotional learning experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic (Elias, 2020; World Health Organization [WHO], 2020). Quotes from the survey’s five constructed response questions (questions three through seven) are shared in the narrative context addressing each question in this article. The survey achieved construct validity, in that it measured what it was intended to measure. In addition, all seven questions were answered by all respondents (N = 46). Noteworthy was the number of respondents and their detailed and lengthy constructed responses.

The seven questions of the qualitative survey follow, addressing the question, “What is the future of arts education?” while in the midst of the COVID-19 epidemic and pandemic.

Survey Questions

- What type of learning situation best describes your teaching/learning situation?

- What level of students do you work with? Or if a student, what level are you? If you teach more than one level, which level do you most identify with?

- What do you see (your vision) as the future of education? (visual arts education or arts education or education in general)

- What role is technology playing in your teaching/learning? What role will it play?

- How do you think your teaching and learning will be different in the future (next year)?

- What are your students, parents, children sharing with you about teaching and learning?

- Describe the biggest challenges you are facing during this time of online learning (communication, planning, grading; etc.)

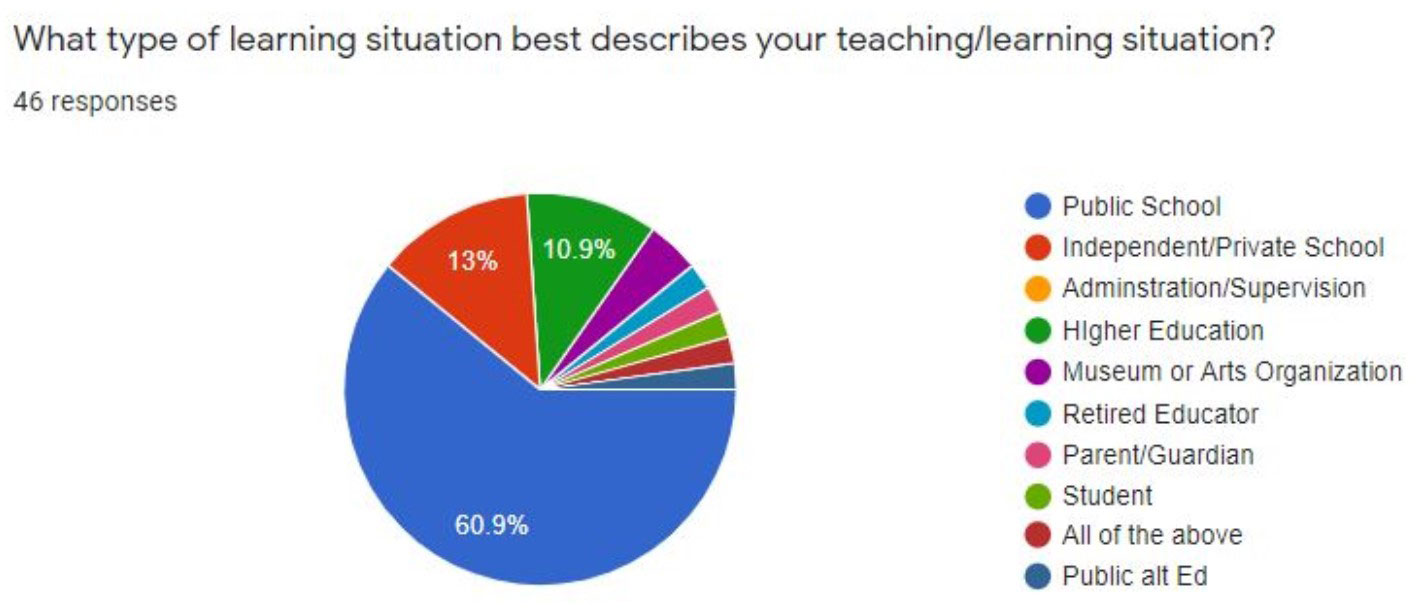

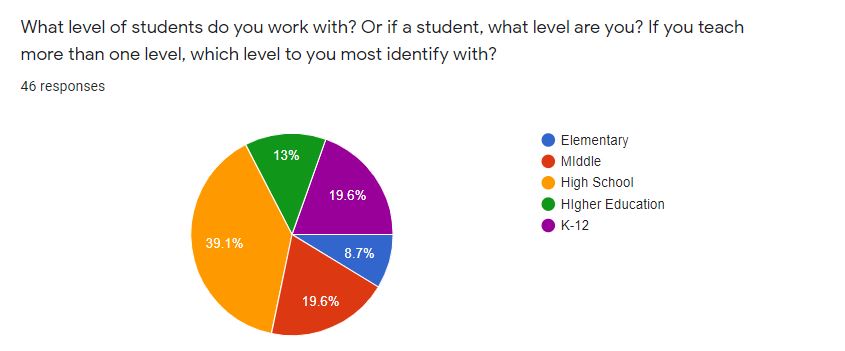

Figures 1 and 2 describe the 46 respondents, answering questions one and two on the survey.

Survey question number one: What type of learning situation best describes your teaching/learning situation? The types of learning situations that best describe the 46 respondents include: 28 public school teachers, six independent or private school teachers, five higher education teachers, two museum or arts organization personnel, and one respondent each from retired educators, parent or guardian, student, public alternative education teacher, and all of the above, which included administration. The categories represented in the survey are illustrated in Figure 1.

Survey question number two: What level of students do you work with? Or if a student, what level are you? If you teach more than one level, which level do you most identify with? The educational levels taught by the N = 46 respondents included: four at the elementary school level (grades kindergarten to five or six), nine at the middle school level (grades six, seven, and eight), eighteen at the high school level (grades nine, ten, eleven, and twelve), six at the higher education level (college and graduate school students and professors), and nine encompassing all levels kindergarten through grade twelve. The categories are represented as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Pie Chart describing grade levels taught or grade levels of student of the survey respondents N = 46.

Survey question number three: What do you see (your vision) as the future of education? (visual arts education or arts education or education in general)? Predictions for the future of teaching arts educational possibilities continue to be virtual, blended, on-line, computer-based, distance-learning, and remotely via synchronous and asynchronous formats and platforms. A survey respondent wrote:

I feel like this question would have been answered very differently three months ago. I think the future of education means re-inventing the way we teach and how to best use our skills and resources to allow for student understanding with necessarily working alongside the students. Arts education is crucial for all humans – it allows us to activate imagination which leads to innovation, collaboration which informs connection and community. It continues to be our deepest level of commonality as human beings. Arts education fosters whole human development. Arts education must be on the forefront of culturally relevant teaching, social justice in education and compassionate community building. (respondent to survey question #3, May 2020)

School buildings may or may not be used. Students may attend school year-round, and with smaller class sizes, attending classes on alternating days or weeks. Furthermore, school buildings may be restructured and redesigned to become schools for certain subjects across the grade levels pre-school through high school (PK-12) such as ‘arts schools’ for visual, performing, and media arts. Safety gear for all school personnel and students such as masks and gloves may be required. Survey responses provided insight into the myriad technical and virtual methods teachers, students, parents, and administration are currently utilizing to teach, reach, collect, access, assess, grade, and celebrate student accomplishments in their arts courses and coursework at this time. Many advanced classes such as Advanced Placement (AP), and International Baccalaureate (IB) classes, specifically in the arts, already had established and on-line and virtual protocols for submission of portfolio coursework. Imagination, perseverance, persistence, patience, leadership, and vision from the education professionals in both public and private schools, from pre-school through high school, and including higher education and graduate school students and teachers, were reported and evidenced in the student samples and work submitted.

Arts education and the artistic processes of creating, performing, presenting, producing, responding, and connecting are designed to be at the heart of teaching and learning in all subjects – in countless interdisciplinary ways, as demonstrated and reported in the philosophical and educational practices in Waldorf Schools (Steiner, 1997). Arts education is naturally social and emotional learning (SEL) (Elias, 2020; Gewertz, 2019), and as such provides racial equity, diversity, cross-cultural and culturally relevant actions, and inclusion (RE,D,&I) through active and project learning opportunities that celebrate the individual student through their unique interests, strengths, talents, skills, and needs (Dewey, 1934, 1938) via learning-by-doing processes.

Survey question number four:What role is technology playing in your teaching/learning? What role will it play? At the time of the survey, school was 100% virtual in nature, and available in either or both synchronous and asynchronous ways. School buildings were closed. Distance education is how teachers are teaching and how students are learning. Teachers are teaching remotely from their homes. Students are learning remotely from their homes. Technology is the main means for connecting and communicating with students. A survey respondent wrote:

It (technology) is playing a giant roll right now, but this is not true [authentic] Arts education. This is a band-aid in a crisis. True arts learning is done in person, be it a master/apprentice exchange of ideas such as in a visual art studio or in the collaborative communities of the performing arts, with students feeding off of each other’s energies and enthusiasm, and growing in the process. (respondent to survey question #4, May 2020)

Traditionally, students have experienced arts education in school settings with teachers and students working together in real time. This type of learning is difficult to replicate by watching a computer screen, video, whether by via virtual synchronous and asynchronous formats. The learning curve for teachers, students, and parents has been steep. Technical difficulties can be attributed to equipment issues at student and teacher homes, as well as at the schools. Problems stem from connectivity, and access to connectivity, or technical difficulties that result from logging in, learning how to use Zoom, restrictions on computers, and a myriad of other issues reported in the survey, one being email overload and computer or iPhone storage availability. Furthermore, a lack of appropriate computer equipment by students and teachers, a lack of professional development from districts to teachers, and a lack of interest from 50% or more of students and parents who have ‘opted out’ during the pandemic, has exacerbated the situation at all levels, including all of the safety issues associated with the Internet. Teaching and learning virtually feels disconnected, and inauthentic. Engagement and relationship with students, parents, and colleagues can be disjointed, unbalanced, and uncomfortable. An essential question regarding equity and access follows: “Will schools provide every student with an iPhone, laptop (computer), and internet access in their homes?” Connectivity in some rural and remote school districts is often problematic. Internet equipment and connectivity favor wealthier students. One visual arts teacher reported that she sent out a survey of 20 art supplies she wanted her students to have at their homes. According to her survey from her students, the only two resources that her students already had at home were pencils and scissors.

Survey question number five: How do you think your teaching and learning will be different in the future (next year)? At the time of the survey, all education was being delivered remotely in Washington State in spring 2020. A survey respondent wrote:

I believe my teaching will be more focused on the individual, as opposed to the group in my future teaching. We will all become better at using technology to teach and engage with art. However, dance is about the body moving in space and time and its true power is greatly reduced when we cannot physically move together. In the future technology will play a major role, but not the only role. We will prioritize in-person educational experiences as meetups for labs and projects that require human interaction. [I think that] educational processes that require touching and handling specialty materials, a specific type of workspace, and/or person to person contact, such as creating a plaster face mold will be scheduled. The teacher and student will not necessarily meet on a daily basis. (respondent to survey question #5, May 2020)

At the time of this writing, most education is delivered virtually in Washington State in fall 2020. How education is delivered will be locally controlled by districts and by counties, depending upon the containment of the virus and the risks for students, staff, parents, and communities, and according to State health, school district, and local infection rates, including the comorbidity needs of students, staff, and parents (OSPI, 2020a; Washington State Department of Health [WSDoH], 2020).

Survey question number six: What are your students, parents, and children sharing with you about teaching and learning? For some students, their arts classes are the main reason they come to school, (or came to school), and they take as many arts classes as possible during their school years. A survey respondent wrote:

I have three teenagers. One is in private school due to ADHD and being on the spectrum, and two are in public school. I’m a supporter of public education. I see my student in private school has a mentor, 1:1 time with teachers, and strong personal relationships with teachers. He told me it’s the first time he ever felt smart – when he was a high school junior (grade 11-age 17)! It breaks my heart. Every kid should know they are smart, be told they can learn, and have that encouragement at school. My daughter (10th [grade-age 16]) is not learning much online. She’s doing minimum, has stress/depression/anxiety, and a 504 plan. She’s unmotivated. Not one of her teachers has had any personal interaction with her in online learning. Even in visual arts (which she loves) the teacher makes kids watch YouTube videos and do assignments. I don’t think this is ideal. We have to do better. My third child (10th [grade-age 16]) is self-directed. He gets straight A’s and it comes easy to him. He does study. I don’t know if he likes online learning. At this point, teachers take roll and email kids assignments. Everything is posted to Google docs. There isn’t much live virtual teaching going on that I’ve heard about. I know kids are missing out, and this won’t work for every student. With planning and better tools, some online learning could have potential. Again, it’s not great for learning language and getting real-time feedback. It’s ok for writing and math, but the screen is a barrier between student and teacher. I feel the same in meetings with people on laptops. It’s a barrier. People don’t look each other in the eye. (respondent to survey question #6, May 2020).

Students enjoy creating, performing, presenting, producing, responding and connecting, through these artistic processes and ways of knowing as to how they discover the dancer, musician, thespian, visual artist, and media artist inside of themselves through teachers who love to teach arts education and are skilled at doing so. Students are interested in arts education—some in a specific arts discipline or two, and some in all five arts disciplines, and a mix of them — referred to as integrated arts (Joseph, 2019a, 2019b). Parents and student respondents reported that arts education was also described as therapy; as well as, an effective equalizer and a safe place to learn and express freedom for students of diversity, disability, and exceptionality. Students missed their teachers, their friends, their schools, and their learning communities and activities before, during, and after school. School is social, and students and teachers go to school to be social (Dewey, 1900 & 1902/1990, 1916, 1934, 1938).

Survey question number seven: Describe the biggest challenges you are facing during this time of online learning (communication, planning, grading, etc.). The reports from the survey indicate that only 30% to 50% of students are regularly participating, if that many. This is a challenging fact and is a huge detriment to accurate grading and accountability for each student, due to many issues that either enhance or limit student participation. Practices regarding attendance and completion of student work and grading were different for every respondent. Frustration, exhaustion, and a sense of imbalance with time, talents, teaching, parenting, working, living, and resting were reported by teachers, particularly eyestrain, lack of exercise, and emotional challenges. A survey respondent wrote:

Finally —planning for online theatre is painful. When young actors don’t have consistent feedback in the form of words or even physical energy, it is incredibly challenging for them. Imagine trying to pretend to play an instrument – with no sound, no physical keys to play, etc. – it’s pretty hard to work on improving when you don’t have the physical in front of you. Young actors do not have the training to use the technology, let alone apply acting skills for the camera —by themselves! I know there are a lot of creative solutions happening all around but it’s exhausting. I fear that the arts in education will be damaged during this time when, indeed, this is when we need creative outlets the most. (teacher respondent to survey question #7, May 2020)

Unfinished projects, the lack of the ability to teach all types of arts; such as those that require equipment found in art rooms like kilns, art presses, inking stations, large instruments, staging, set and lighting design boards, media arts equipment and technologies, and including a plethora of small supplies and materials, as well as, instruments, and costumes —are all unavailable to the masses of visual, performing, and media arts students studying from and in their homes. Although some limited 2-dimensional (2D) and 3-dimensional (3D) visual arts projects can be done at home, many projects—including ceramics, sculpture, and other types of art making—are left unfinished and yet to be made at school sites. Additionally, the student performances, and presentations, and the personal communications from teachers via emails, phone calls, and virtual Zoom meetings and events (and how to navigate them) report how everything is different— and for some—nothing is the same. Some have used phrases such as being in limbo, unfinished business, lack of vision, disjointed communication, mixed messaging, and chaos. Parents reported feeling inadequate and unqualified. However, home-school parents are feeling validated and have become mentors to other parents as to how to teach one’s children from home via blogs, social media, and virtual meetings.

Respondents reported that they are working longer hours, days and nights are blurred, they are out of their comfort zones, exhausted by the need to learn and employ new technological strategies, struggling with technology and old equipment, in need of professional development, uncertain about their future, feeling isolated, and not sure they want to continue to teach in this type of environment. One middle and high school teacher shared her feelings to the survey via a personal email and granted permission to share it in this paper. She wrote:

Online learning has made teaching seem disconnected and somewhat insincere. Students are learning through pre-recorded videos, unending assigned readings, and project handouts, even in art classes. As a teacher, I know this is the type of learning that students disconnect from and I am actively combating in my own online classes. I will explore strategies for how we can connect with students and create communities both in person and from a distance. My vision for education is a model that places emphasis on the psycho-social needs of students and teachers as the place to start any practice or policy. Students cannot learn or be free to express themselves if they do not feel like a valued member of an art community first. (teacher respondent personal communication May 2020)

Some respondents and personal emails reported that arts classes are being considered for elimination to save money, or that their positions (if retiring) are not being replaced. Enrollment, budgets, teacher attrition, the governor’s proclamation regarding the safety of employees over 65 or those with comorbidities, the lack of district vision or decision-making, and the overall responsibility of keeping students safe in an environment requiring the sterilization of all resources that students share (which is practically everything in visual, performing, and media arts classes) has some teachers concerned to the point of depression and despair.

District and parent expectations that teachers provide learning experiences, engagement, relationship, authenticity, accountability, and transformative actions via remote practices, has been convoluted, challenging, and exhausting, according to respondents. The passion for teaching and making a difference has dissipated. Respondents were honest in sharing their frustration as to how to teach their students, and the need to teach and parent their own children, and how it had placed some educators at a breaking point. Personal basic needs and survival in the current reality has replaced the goal of meeting and exceeding educational expectations and state standards in the arts or any subject.

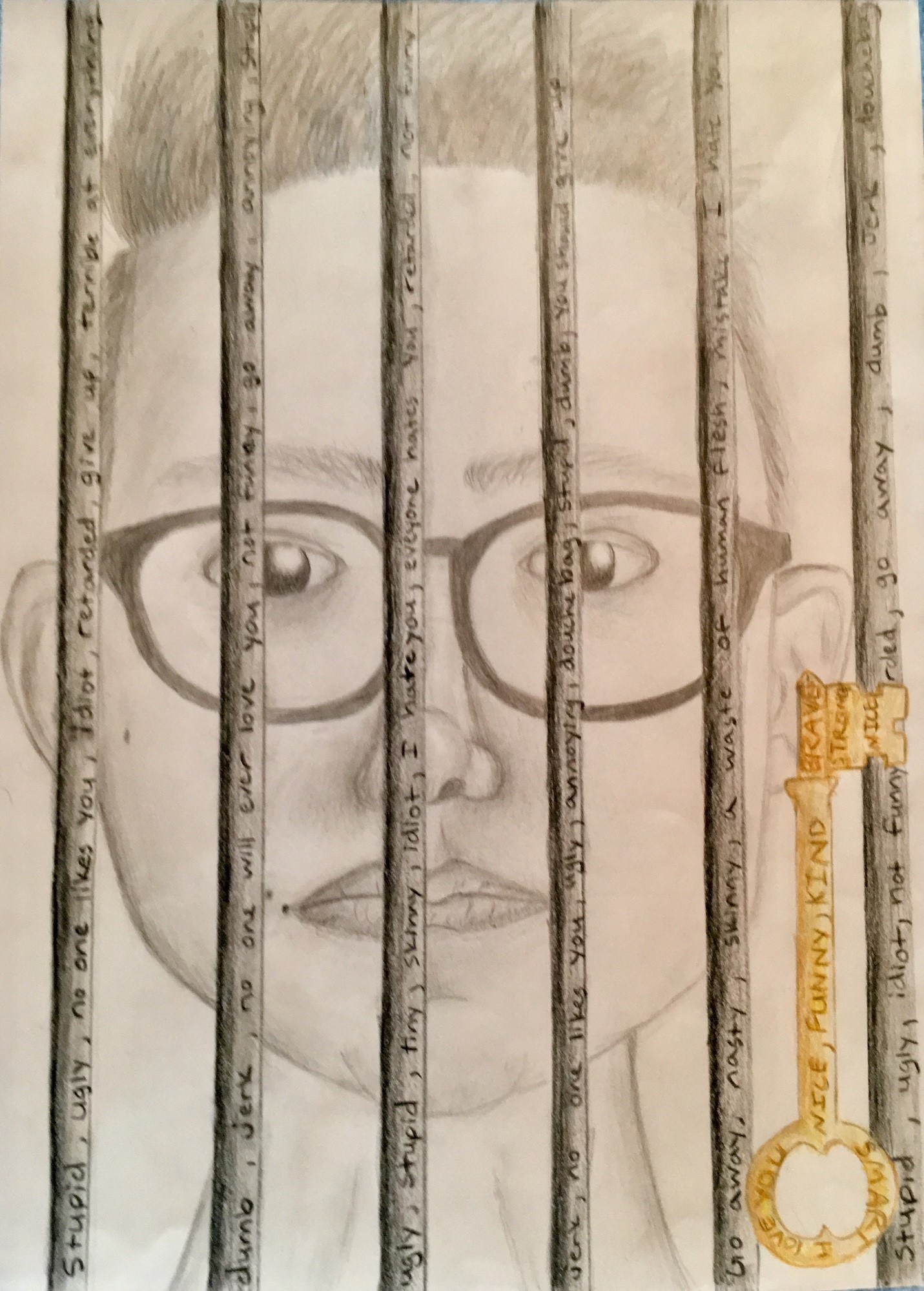

Arts Performance Assessments

Resources and lessons were and are areas of immediate and constant concern of educators and parent respondents. Teachers shared that the OSPI Performance Assessments for The Arts (OSPIa & OSPIb, 2003, 2006, 2008, 2011, 2015, 2018, 2019ii; WSL, 2004/2006/2011), were on-line, free, self-explanatory, and easy to access and use directly from the OSPI arts website, or by downloading. There are currently 74 arts performance assessments available for use (and being used) by individual students and teachers in their areas of interest and study. Each arts performance assessment is aligned to state arts learning standards and includes a rubric for scoring individual progress and directions for administration for parents or students. Each is easily adaptable to any age and any learning environment and provides limitless possibilities for essential learning in the visual, performing, and media arts (Joseph, 2019c; OSPI, 2011). A student’s sample and adaptation, from a visual arts performance assessment ([APAs] – formerly Classroom-Based Performance Assessments [CBPAs]), is included in Appendix B. It is evident from her artwork that she felt trapped, unhappy, and unlikable. Her artist’s statement—also referred to as a reflection, was included as a part of her artwork. The honesty in the artwork is compelling. The arts performance assessments provide these experiences on an individual, personal, and unique basis, are research based via three statewide pilots indicating validity and reliability, and applicable to any type of learning environment—in or out of a traditional school setting. Further, these particular resources address key issues of social-emotional learning for all learners, via individuality, justice, equity, access, and inclusion for special needs, exceptionality, and gender identification. Noteworthy, the arts performance assessments are adaptable to any type of learning environment; such as home-school, private school, private tutoring, home-hospital, incarcerated or system involved students, and any type of alternative learning situation – from pre-school through grade twelve; as well as in school settings, and for professional development and higher education instruction. The 74 arts performance assessments are available free with the click of a mouse (beginning in 2004 – current) on one’s computer or iPhone and ready for download or use from on-line. They were created with vision for such a time as this, with no expiration date. They are adaptable to all grade levels and all students in any learning situation, and can be utilized as resources prior to, during, and following instruction to see student growth for self-assessment, accountability, and for student portfolios of produced work over the course of the school year. Accessing other visual, performing, and media arts resources was challenging and time-consuming for all educators responding, taking up hours of their time before and after their school days ended and on weekends. Resources varied as to teacher engagement in finding, posting, and utilizing other education sites. Security issues were mentioned.

Arts Education is a Core Subject and Graduation Requirement Requiring Certificated Staff in Washington State

Licensed and certificated arts educators in visual, performing, and media arts courses are skilled in designing pathways and possibilities for students to take all of the arts education classes that interest them, and for high school graduation requirements (WSL, 2014, 2019). Further, these educators are skilled in knowing how students learn, and are able to successfully present arts instruction that causes students to love arts classes and activities that additionally provide social, emotional, and necessary skills for success in life and work (Dewey, 1934, 1938; Quintilian, 1938). Many media arts classes are taught by career and technical education (industry) staff, in addition to those certified arts educators who are dual certified to teach traditional or technical arts education. These purposeful partnerships, collaboration, and dual credit opportunities provide possibilities to keep students engaged in active, hands-on, project, and ‘learning-by-doing’ schoolwork that interests them (Bolin, 2020). This type of instruction provides meaning and transfer in all four learning styles – aural, visual, kinesthetic, and tactile formats (Dunn, & Dunn, 1992), reaching all types of learners through their strengths, talents, and skills, and leading to success and achievement. Students choose the arts teachers they want and form relationship with their teachers at the secondary levels—for required and elective arts courses. Teachers who are skilled at what they teach—specifically in the arts—are able to convey their passion, skills, talents, and love of the subject matter to the students they teach. Most elementary students have access to arts specialists in dance, music, theatre, and visual arts, if schools and districts provide them. Arts education is locally controlled; although state and federally mandated by laws and policies and required as a high school graduation requirement (WSL, 1993, 2015).

Survey Predictions for the Future of Arts Education

The future of arts education and how it will be taught to all learners is mostly virtual for now, and at the time of this writing, via technologies using synchronous and asynchronous methods. Exactly ‘how’ arts education will happen in the future is uncertain, especially in the performance subject areas of music (choirs, bands, and orchestras), theatre (drama and creative dramatics), and dance, due to saliva spray from singing and playing instruments, speaking and chanting, and body sweat while dancing, acting, and moving, and the interactive nature in these collaborative performing arts subjects (Hamner, Dubble, Capron, et al., 2020). Visual arts and media and graphic arts are easier to teach and experience via distance learning modes, and to individualize by student, due to the content, equipment, resources, and individual introspective nature of these subjects. Many teachers and students want to be back in the classrooms. Keeping students engaged in the arts, participating remotely, and learning in the arts are challenging in and out of school settings. Supplies and materials, equipment, resources, and endless possibilities in classrooms designed and prepared for visual and performing arts classes are available, albeit mostly empty at this time. Getting arts education resources into the hands of students and parents remains challenging and exacerbates issues of equity and access. Issues and challenges remain as to how to keep students, staff, teachers, and families safe in schools and during school activities during the school day, as well as before, and after school. Currently, a universal vaccine is not available for COVID-19, and the ability to supervise and safely social distance is questionable for in-person school and instruction. Arts education is essential; yet, how to provide it remains challenging —even daunting.

Student Survey

A high school student (grade 11) felt compelled to conduct a survey of her peers following the conclusion of the 2019-2020 school year, from June 22, 2020 to August 22, 2020, to find out how students were coping during the pandemic, and their need for arts education. Her developing report, entitled: Continuing Arts Education: Student Survey Report (Knauss, 2020), surveyed arts students on the five areas during the COVID-19 outbreak and shutdown of in-person school. Those five areas are social-emotional, mental, and physical health, student participation in the arts during the pandemic, and student favorite things about their artform and what they were looking forward to once the pandemic ended. Her survey included 668 student respondents in grades kindergarten through twelve, attending 122 schools, and representing 20 of 39 counties in Washington State, as illustrated in Figure 3. Respondents were contacted via private social media accounts on Facebook and Instagram, and through personal email, including local community groups and the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) Arts Advisory Team. Repeated and on-going social media posts regarding the survey and survey link continued throughout the two months of the survey. Plans are underway to share the survey results in October 2020, as well as follow up with survey respondents in winter and spring 2021 (personal phone interview with student survey author on July 31, 2020 and personal communication via email on September 13, 2020).

Knauss (2020), sent a personal statement (via email) regarding her current school year. This statement follows, in its entirety, and with her permission to share it in this paper. She is currently working on a final report of her survey, a PowerPoint, and a statewide link to her report. She is currently a high school senior. She attends a public high school, in a suburban school community in Southeast King County, Washington State. Her 2020-2021 learning model is remote at the time of this writing, and described in detail following, with her permission. Her survey, personal statement, and personal interviews validate the premise of this paper regarding arts education as essential to all learners, it’s current remote and virtual format—and the challenges that presents. Her personal statement shares how her arts classes and school are being taught this year, and their personal importance:

My district opted for a full remote start to the 2020-2021 school year. For middle school, students have six classes and take three each day on a block schedule. My sister currently uses that schedule, as she is in 7th grade, and enjoys it very much. As for the high school, the adopted schedule features eight total classes throughout the year, with the first four classes for the first quarter, second four for the second quarter, and it may repeat for the second semester. Though I was disappointed with the district in pursuing this choice, especially considering the large amount of backlash from students, parents, and the community, I have found the school year enjoyable so far. I will only have choir for first quarter, no arts classes second or fourth quarters, and will have choir and theatre for third quarter. I am in my school’s chamber choir and am the choir’s alto section leader. We use Zoom as our rehearsal platform. We attempted singing with multiple students at once, but the platform could not focus on more than two singers at a time. However, we rehearse in our sections by choosing a part of a piece and assigning a few measures to each member in order to hear each other, establish the tone for our section, and to work out any mistakes in the section. This has worked well for our choir, and I am now much more confident in how successful our virtual choir will be and look forward to singing each day. We also work on melodic dictation, singing together while on mute, and are given assignments to expand our knowledge of choral literature and music theory. My director is also taking time to hold private lessons with each of us to work on a piece of solo literature, which I know that many members of my choir (including myself) are thrilled about! I truly believe the arts are resilient and will be able to grow and thrive in the environment they are given, and I am so impressed with every arts educator I have spoken with over the summer and since the start of the school year. The effort and care they have shown for the arts and students have been strikingly clear and is greatly appreciated. Students are losing some critical aspects of the arts, whether it be performance, mediums, or a space to create, but in these times, they can be shown just how essential the arts are and how art can be found everywhere in our lives. (Knauss, personal communication, September 4, 2020)

Singing and Playing Wind and Brass Instruments

Singing is a necessary activity that provides health to individuals via the vagus nerve (Gould, 2019). Sadly, singing in the classroom, church, and community choirs has been deemed unhealthy, at this time, due to the saliva spray that naturally occurs while singing (Hamner et al., 2020). Noteworthy, regarding singing at home and virtually (for now), is that healthy internal actions occur via synergy of the vagal nerve throughout the body organs—originating in the brain stem and wandering throughout the body to the abdomen. Deep breathing, humming, singing, chanting, and choir (choral) warming up exercises naturally activate the vagal nerve, producing healthy vagal tone, and activating the parasympathetic nervous system in healthy ways. Vagal tone occurs naturally when one hums in an intentional low tone with the mouth closed. This action creates a natural buzzing sensation in the lips, mouth, and nose area, and easily activates singing; thus, relaxing the parasympathetic nervous system. This exercise is used daily and often with singers, and especially in school choirs, as a ‘warm-up’ and transitional activity. These choral ‘warm-ups’ can be attributed to personal and physical relaxation; naturally resulting in less stress with students and adults, and creating a sensation of joy, hope, and happiness in singers. Gould (2019) wrote, “The vagus nerve serves as the body’s superhighway, carrying information between the brain the internal organs and controlling the body’s response in times of rest and relaxation.” Schools would do well to encourage their students to sing at home as a soloist, with their siblings and friends, and with their parents and family— individually and collectively— albeit while social distancing and wearing a shield or mask if singing in close proximity with others; and in addition to taking choir at school. Virtual choirs, bands, and orchestras are becoming an entertaining and challenging norm for the present, and music educators are embracing the steep learning curve necessary to collect, record, and produce productions with their music groups via synchronous and asynchronous virtual platforms. The same is occurring with wind and brass instruments and practicing safely so that saliva is not sprayed onto others. Teachers of music education teach students to buzz and hum into instruments, while playing instruments, and while singing. It is a practice that stimulates cognitive, social, and physical health—relieving stress through musical instruction and actions. Recording links to video and YouTube performances by virtual choirs, bands, orchestras, and community groups—some being international and world-wide in scope—were sent with survey responses revealing the success of such efforts.

Qualitative Survey Insights

Significantly, the shared responses from a qualitative survey via a state arts education organization, a student survey, research, student samples, and personal testimonies emphasizing the importance and necessity of arts education, have been presented in this article in support for the rationale that study in the arts is essential, basic, core, and academic for all learners—at any age and in every type of learning situation (Arts Education Partnership [AEP], 2002; Edgar, & Morrison, 2020; Fortune, et al., 2020; Gould, 2019; Knauss, 2020; NAfME, 2020; NCCAS, 2014; OSPI, 2020b; SEADAE, 2020).

Teacher and survey respondent quotes provide insight as to how teaching and learning was thrust into instant change, and how those responsible for the care, health, safety, and learning of students coped, adapted, struggled, and survived a future of education in flux (Frey, 2007; OSPI, 2020a; WSDoH, 2020). The rapidly changing and unknown landscape appeared daunting, and required resilience, persistence, patience, perseverance, and fortitude. Frey (2007) had predicted and written about this type of educational transition; albeit in futuristic terms and prior to the existence of most of the current technological advances available at the time of this writing; whereas, classroom and school based learning would transition to anyplace and at any time; mandated and required coursework would transition to hyper and interest based learning; teacher directed or centric instruction would transition to learning and learner centric interests; and consumer learning would transition to production learning—all of which would be supported and sustained by technology improvements over time that would continuously improve the speed of access and comprehension in learning. His predictions eerily resemble what happened and could be considered prophetic as to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic—espousing positive outcomes.

Student samples in Appendix B provide examples of success, communication, creativity, adaptability, resilience, collaboration, engagement, and innovation on the efforts of teachers, students, parents, and administration to keep arts education essential, core, basic, academic, and available to all learners, as part of an well-rounded education for the whole child (Jones, 2018/2019; Joseph, 2006, 2014, 2019a, 2019b, 2019c, 2020a, 2020b, 2020c; OSPIa & OSPIb, 2003, 2006, 2008, 2011, 2015, 2018, 2019, OSPI, 2011, 2020a, 2020b; USDOE, 2015; WSL, 1993).

Conclusion

This paper reported how arts education is essential—now—and in the future in five areas: social-emotional well-being, academic achievement, cognitive enhancement, health, and as an essential part of basic education for all learners (OSPI, 2020a, 2020b; WSDoH, 2020). Specifically, it has presented the notion that arts education is essential in and of itself. Arts education—as discussed—encompasses three framing areas, referred to as: arts for ‘art’s sake’—the study of each arts form—dance, media arts, music, theatre, and visual arts for what each individual arts discipline provides to life and learning; ‘integrated arts’—describing how arts subjects naturally integrate, interweave, and connect together with the other arts: dance (creative movement, improvisation, choreography, and private study), media arts (technology and video formats naturally embedding into the visual and performing arts), music (singing and playing instruments, body percussion, and private study), theatre (creative dramatics, drama, acting), and visual arts (drawing, painting, creating, making art in two and three dimensional formats, and photography); and ‘arts in the content areas’—often referred to as ‘arts integration’ or ‘interdisciplinary arts’—and their natural integration via the artistic processes of creating, performing, presenting, producing, responding, and connecting—and interweaving into other core and academic subjects, which are: reading, writing, mathematics, science, social studies, health and fitness, visual and performing arts, communication, and technology in Washington State (Eisner, 1992; Edwards, 1986; Ellis & Fouts, 2001; WSL, 1993; Zull, (2002). Further, the efforts of this reporting are to advocate that arts education, in all three of these framing formats (arts for ‘art’s sake’; integrated arts; and arts in the content areas), remains essential for all learners in the midst of a world-wide pandemic, school closures, and ‘stay-at-home’ mandates, and the future.

Transition to 2020-2021. Students are returning to school at this time via hybrid formats; mostly remotely—in Washington State—depending upon locally controlled determinations (WSDoH, 2020). Their social-emotional learning (SEL) is as important as their intellectual and cognitive learning, and has taken a forefront since the pandemic, as students have expressed emotions of sadness, anxiety, loneliness, trauma, depression, fear, and anger from not being able to go to school, be with their friends, and experience the traditions and activities of school, summer vacation, work, and social life. The visual and performing arts have been cited as some of the most effective methods to address these social-emotional learning needs (Edgar & Morrison, 2020; Elias, 2020; Farrington, Maurer, McBride, et al., 2019; Gewertz, 2019; OSPI, 2020b; SEADAE, 2020), and as powerful learning modes to assist students in reflecting, refocusing, and moving forward in their lives and learning (see Appendix B). Social-emotional skills learned in and through arts courses assist students to develop the ability to experience, express, and manage their emotions in productive and positive ways. Students, teachers, and parent respondents shared that study in the arts assisted students to feel and demonstrate empathy, understanding, resilience, collaboration, community, belonging, reflection, social justice, racial equity, diversity, and inclusion (RE,D,&I), and communicate effectively. Role-playing, creative dramatics, drama, dance, movement, singing, playing instruments, performed poetry, imaginative play, and the creation and composition of such are all integral elements of the performing arts that relate and invite success via creativity to most learners across the grade levels (Jones, 2018/2019; OSPI, 2011). Possibilities for creative visual and performing arts instruction and activities, via the artistic processes—are endless. Arts instructional opportunities will occur if given time to occur—whether in person, on-line, in small groups, or at home—and provide hours of meaningful, transferable, and life-long lessons. The arts and education are valuable life experience for every and any learner (Dewey, 1934, 1938; Housen, 2001-2002).

Visionary leadership, advocacy, action, and passion to ensure that arts education remains a part of a well-rounded education for every student has inspired and motivated arts educators, parents, students, teachers, administrators, and advocates to showcase arts education in virtual ways that were experimental, imagined, and desired. It is a time in history that school systems have the opportunity to design, re-design, adjust, adapt, reinvent, and reimagine how to better serve each individual student with an Individual Education Plan (IEP), such as are required for students of disability and exceptionality, and cross-culturally, while continuing to provide an essential and complete education for all learners which includes visual, performing, and media arts (SEADAE, 2020; OSPI, 2020b; WSL, 1993, 2014; U.S. Department of Education [USDOE], 2015).

The pandemic has caused havoc on the world at large. Arts education is essential, and will continue to provide social, emotional, cognitive, physical, and mental health to any and all who participate and express their learning in creative ways—virtually or in person. Persons experiencing and engaging in instructional opportunities through dance, media arts, music, theatre, and visual arts—via the universal nature of the artistic processes of creating, performing, presenting, producing, responding , and connecting—create a sense of normalcy, possibility, community, and hope during this challenging and uncertain time in history.

Visual and performing arts educators are redesigning, reinventing, and reimagining how they will successfully and artistically deliver instruction remotely, virtually, and in hybrid models. Arts educators are determined to be successful and demonstrate resilience in the face of adversity and ambiguity. Waldorf Education is a an international educational philosophy of theory into practice, where arts education is at the heart of most all teaching and learning methods—indoors and outdoors—providing a time tested educational model to replicate at home, on-line, and in hybrid instruction (Steiner, 1977). Arts educational processes provide rigor, relationship, and relevance of ‘learning-by-doing’ via the artistic processes of creating, performing, presenting, responding, and connecting—resulting in life-long learning experiences that teach and inform student and adult learners throughout their lives. Arts education produces such effects (AEP, 2002; OSPI, 2020b; SEADAE, 2020).

This is a time of change and transition—a refocusing on what needs to be taught, and how—with the intention that students remain interested in learning about and study in the arts. Positively, the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic could be referred to as a ‘rebirth’ and a world-wide Renaissance in education as a whole—particularly in arts education (Frey, 2009). Teachers, students, parents, school administration, and teaching artists are working collaboratively to champion and ensure arts education is accessible to all learners (AEP, 2002; Booth, 1997, 2007; Eisner, 1992; OSPI, 2020b; SEADAE, 2020). Arts education will survive and thrive, as it is a basic need of all peoples—a celebration of world-wide culture, diversity, creativity, and humanness. What is the future of arts education? Arts education is essential!

References

- Arts Education Partnership. (2002). Critical links: Learning in the arts and student academicand social development. Washington, DC: Author.

- Bogdan, R. C., & Knopp-Biklen, S. (2007). Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theories and methods. (5th Ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

- Bolin, P.E. (2020, September). Looking forward from where we have been. In Art Education: The Journal of the National Art Education Association, 73(5), pp. 44-46.

- Booth, E. (1997). The everyday work of art. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks.

- Booth, E. (2007, Fall). Learning and yearning. In Teaching Theatre, 19(1), pp. 5-13.

- Dewey, J. (1900 & 1902/1990). The school and society. The child and the curriculum. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago.

- Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. New York, NY: McMillan.

- Dewey, J. (1934). Art as experience. New York, NY: Perigee.

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience & education. New York, NY: Touchstone.

- Dunn, R., & Dunn, K. (1992). Teaching elementary students through their individual learning styles. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon, Inc.

- Edgar, S. N., & Morrison, B. (2020). Advocating for music education using social emotional learning. In Teaching Music. Vol. 28(1), pp. 20-22.

- Edwards, B. (1986). Drawing on the artist within. New York, NY: Fireside.

- Eisner, E. W. (1992). The misunderstood roles of art in human development. In Phi Delta Kappan, 73(8), pp. 591-595.

- Elias, M. (2020). Help students process COVID-19 emotions with this lesson plan. In Greater Good Magazine: Science-Based Insights for a Meaningful Life. Education | Articles & More. URL: https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/help_students_process_covid19_emotions_with_this_lesson_plan

- Ellis, A. K., & Fouts, J. T. (2001). Interdisciplinary curriculum: The research base. In Music Educators Journal, 87(5), pp. 22-68.

- Farrington, C. A., Maurer, J., McBride, M. R. A., Nagaoka, J., Puller, J. S., Shewfelt, S., Weiss, E.M., & Wright, L. (2019). Arts education and social-emotional learning outcomes among K–12 students: Developing a theory of action. Chicago, IL: Ingenuity and the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research. URL: https://consortium.uchicago.edu/sites/default/files/2019-05/Arts%20Education%20and%20Social-Emotional-June2019-Consortium%20and%20Ingenuity.pdf

- Fortune, T., Gillett, C., & Joseph, A. (2020). Arts education now and in the future – Practice, research, and theory in the middle of a pandemic. Presentation presented during the Arts Education Partnership (AEP) Virtual Gathering 2020, Arts Education Partnership, and Education Commission of the States, Denver, CO. URL: https://vimeo.com/453824846/7e3b5648ed

- Fowler, F. J. (2009). Survey research methods. (4th Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Frey, T. (2007, March 3). The future of education. In Business Trends. URL: https://futuristspeaker.com/business-trends/the-future-of-education/

- Gewertz, C. (2019, June 26). How arts teachers are strengthening students’ social-emotional muscles. Education Week.URL: https://mobile.edweek.org/c.jsp?cid=25919801&bcid=25919801&rssid=25919791&item=http%3A%2F%2Fapi.edweek.org%2Fv1%2Few%2Findex.html%3Fuuid%3D572FCD68-9784-11E9-BF41-B4F258D98AAA

- Gould, K. (2019, November 12). The Vagus Nerve: Your body’s communication superhighway. In Live Science. URL:https://www.livescience.com/vagus-nerve.html

- Hamner, L., Dubbel, P., Capron, I., Ross, A., Jordan, A., Lee, J., Lynn, J., Ball, A., Narwal, S., Russell, S., Patrick, D., & Leibrand, H. (2020). High SARS-CoV-2 attack rate following exposure at a choir practice — Skagit County, Washington, March 2020. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2020; 69, pp. 606–610. URL: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6919e6.htm

- Housen, A. C. (2001-2002). Aesthetic thought, visual thinking and transfer. In Arts and Learning Research Journal, 18(1), pp. 99-132.

- Jones, S.D. (2018/2019). ESSA: Mapping Opportunities for the Arts. Denver, CO: Education Commission of the States. URL: https://www.ecs.org/wp-content/uploads/ESSA-Mapping-Opportunities-for-the-Arts.pdf

- Joseph, A. (2006). Arts education is academic, essential, core, basic, and…A requirement in WA State. URL: https://kentprairie.asd.wednet.edu/UserFiles/Servers/Server_3165110/File/Migration/education/page/ArtsEducationisAcademicJanuary2006.pdf

- Joseph, A. (2014). The effects of creative dramatics on vocabulary achievement of fourth grade students in a language arts classroom: an empirical study. Theses and Dissertations. URL: https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1014&context=etd

- Joseph, A. (2019a). Arts and academic achievement—Empirical evidence for arts realities in ESSA and around the world—Arts speak! Presentation presented at the 10th Biennial Symposium: Educational Innovations in Countries around the World – Educational Innovations and Reform, Seattle Pacific University, Seattle, WA.

- Joseph, A. (2019b). Arts and academic achievement—Empirical evidence for arts realities in United States education law and around the world. In International Dialogues on Education: Past and Present IDE-Online Journal, 6(2). URL: https://www.ide-journal.org/article/2019-volume-6-number-2-arts-and-academic-achievement%e2%80%95empirical-evidence-for-arts-realities-in-united-states-education-law-and-around-the-world/ (see also: https://www.ide-journal.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/IDE-2-2019.pdf, pp. 164-198).

- Joseph, A. (2019c). Washington State’s classroom-based performance assessments: Formative and summative design for music education. In T.S. Brophy (Ed.). The Oxford handbook of assessment policy and practice in music education. (Vol. 2) New York, NY, pp. 177-208. Oxford University Press. URL: https://books.google.com/books?id=MpSBDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA194&lpg=PA194&dq=annren%C3%A9+joseph&source=bl&ots=x32OO0x_G-&sig=ACfU3U33UIY3Ug_ADN_ApVZYAPXb841jCw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiFj-j6gdnrAhVNs54KHcUNBtQ4MhDoATAHegQICRAB

- Joseph, A. (2020a). “International symposium survey question – What is the future of arts education?” URL: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSd5KpQQmQkiD96m1v6pnr7Ra-pxlnv2yJcoc4cRFqKwUOCL4w/viewform

- Joseph, A. (2020b). The future of arts education: What is the future of arts education? Presentation presented at the 14th Annual Symposium: Educational Innovations around the World in the Wake of the COVID-19 Epidemic of 2020, Seattle Pacific University, Seattle, WA.

- Joseph, A. (2020c). What is the future of arts education? In Splatter Magazine, 6(4), pp. 26-29. URL: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1xruvGCIYTIOCHcCC0aOEcLRxVxL_MftH/view

- Knauss, H. (2020). “Continuing arts education: Student survey report.” Developing and unpublished survey report.

- National Association for Music Education [NAfME], (2020). Arts education is essential: Unified statement. URL: https://nafme.org/wp-content/files/2020/05/Arts_Education_Is_Essential-unified-statement.pdf

- National Coalition for Core Arts Standards (NCCAS). (2014). In National Core Arts Standards (NCAS). URL:https://www.nationalartsstandards.org/

- Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI). (n.d.) Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) guidance. URL: https://www.k12.wa.us/about-ospi/press-releases/novel-coronavirus-covid-19-guidance-resources

- Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPIa, 2003, 2006, 2008, 2011, 2015, 2018, 2019). OSPI-developed performance assessments for the arts (formerly classroom-based performance assessments [CBPAs]). URL: https://www.k12.wa.us/student-success/resources-subject-area/arts/performance-assessments-arts

- Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPIb, 2003, 2006, 2008, 2011, 2015, 2018, 2019). OSPI-developed performance assessments for the arts (formerly classroom-based performance assessments [CBPAs]) – The Real You. URL:https://www.k12.wa.us/sites/default/files/public/arts/performanceassessments/visualarts/grade8-therealyou.pdf

- Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI). (2011). Washington State K – 12 arts learning standards. Olympia, WA: OSPI. URL: https://www.nthurston.k12.wa.us/site/handlers/filedownload.ashx?moduleinstanceid=24472&dataid=46509&FileName=Arts%20Standards%20OSPI%202011.pdf

- Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI). (2020a). Guidance for long-term school closures as of April 8, 2020. OSPI Bulletin No. 031-20 Executive Services. URL: https://www.k12.wa.us/sites/default/files/public/bulletinsmemos/bulletins2020/6_Guidance%20for%20Long-term%20School%20Closures%20as%20of%20April%208.pdf

- Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (2020b). The arts are essential. URL: https://www.k12.wa.us/sites/default/files/public/wakids/Arts%20are%20Essential%202020.pdf

- Quintilian. (1938). Quintilian on education. Translated by William M. Smail. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- State Education Agency Directors of Arts Education [SEADAE], (2020). In Arts education is essential: Unified statement. State Education Agency Directors of Arts Education [SEADAE], (2020). Arts education is essential: Unified statement. URL:https://nafme.org/wp-content/files/2020/05/Arts_Education_Is_Essential-unified-statement-3.pdf

- Steiner, R. (1997). The roots of education: Foundations of Waldorf education. Hudson, NY: Anthroposophic Press.

- U.S. Department of Education (2015). Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015, Pub. L. No. 114095 § 114 Stat. 1177 (2015-2016). URL: https://www.ed.gov/ESSA

- Washington State Department of Health. (August 31, 2020). Decision tree for provision of in person learning among public and private k-12 students during COVID-19. URL: https://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/1600/coronavirus/DecisionTree-K12schools.pdf

- Washington State Legislature. (1993). Basic education — goals of school districts. URL:

- https://app.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=28A.150.210

- Washington State Legislature. (2004/2006/2011). Essential academic learning requirements and assessments—Verification reports. URL:https://app.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=28A.230.095

- Washington State Legislature. (2014). State subject and credit requirements for high school graduation—Students entering the ninth grade on or after July 1, 2015, through June 30, 2017. URL: https://app.leg.wa.gov/wac/default.aspx?cite=180-51-068

- Washington State Legislature. (2019). WAC 181-79A-206 Academic and experience requirements for certification—Teachers. URL:https://apps.leg.wa.gov/wac/default.aspx?cite=181-79A-206&pdf=true

- World Health Organization (WHO) Headquarters. (2020, March 11). WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. URL:https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020

- Zull, J. E. (2002). The art of changing the brain: Enriching the practice of teaching by exploring the biology of learning. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Appendix A

Survey Questions

- What type of learning situation best describes your teaching/learning situation?

- What level of students do you work with? Or if a student, what level are you? If you teach more than one level, which level do you most identify with?

- What do you see (your vision) as the future of education? (visual arts education or arts education or education in general)

- What role is technology playing in your teaching/learning? What role will it play?

- How do you think your teaching and learning will be different in the future (next year)?

- What are your students, parents, children sharing with you about teaching and learning?

- Describe the biggest challenges you are facing during this time of online learning (communication, planning, grading; etc.).

Thank You

If you have images of yourself and/or student artwork that can be shared on the Internet, please send them to moreartsannrene@gmail.com.

Joseph, A. (2020a). “International symposium survey question – What is the future of arts education?” URL: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSd5KpQQmQkiD96m1v6pnr7Ra-pxlnv2yJcoc4cRFqKwUOCL4w/viewform (retrieved: 2020, June 8).

Appendix B

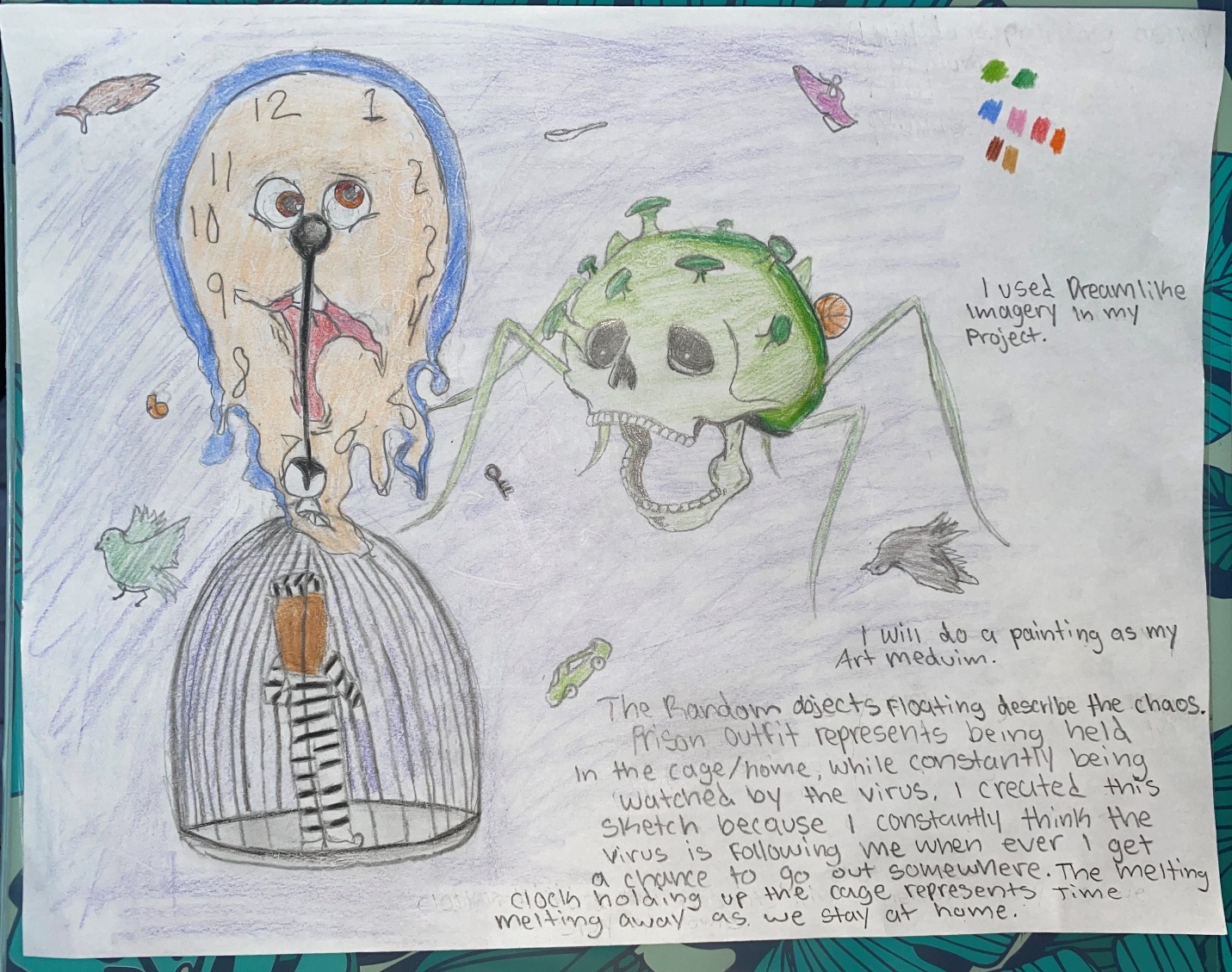

The following student artworks demonstrate, through visual arts, the social and emotional learning impact of the COVID-19 quarantine from school.

Figure B1: Middle school student (Grade eight, age 13-14) artwork adaptation of a Washington State Arts Performance Assessment ‘The Real You’ adapted to ‘The Real Me, 2020’, with student reflection or artist’s statement written on the bars and keys as a part of the artwork (OSPIb, 2003, 2006, 2008, 2011, 2015, 2018, 2019).

Figure B2: Middle school student (Grade eight, age 13-14) artwork rough draft of an assignment of what it felt like to being in the COVID-19 pandemic and not able to come to school, in spring 2020. The reflection or artist’s statement is written on the artwork in this ‘first draft’ and prior to teacher input.

Figure B3: ‘Staring into Madness’, Acrylic on Canvas, 2020. Middle school (Grade eight, age 13-14) Latinx student final submission of an assignment of what it felt like to be in the COVID-19 pandemic and not able to come to school, in spring 2020, following teacher input and instruction. The artist’s statement or reflection statement is written below.

Artist’s Statement or Reflection:

“It is my artistic intention to represent how crazy my life is and how time is going by fast. I decided to make a painting for my project because it’s one of the things I really enjoy. I learned how to mix and blend colors together. I decided to paint the background a bit darker than the rest of the things in the painting so they could stand out more. My artwork is surreal because the clock in the painting is dripping to represent time wasting away and the person in the glass cage with an eye instead of a head, and of course the skull with legs. And, lastly, random objects with bizarre colors.” (8th grade female student communication to her teacher and submitted for this paper, June 5, 2020).

About the Author

Dr. AnnRené Joseph: Chief Executive Officer (CEO) at More Arts! LLC, Educational and Research Consultant, Author: Retired Program Supervisor for the Arts for Teaching, Learning, and Assessment, Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI), Washington State (USA); e-mail: moreartsannrene@gmail.com or josepha@spu.edu

i The article report, qualitative survey, figures, appendices, and quoted survey responses are information gathered from responses to a qualitative survey created to examine the question, “What is the future of arts education?” during the midst of the COVID-19 epidemic and pandemic of 2020, and conducted to present at the 14th Annual Symposium: Educational Innovations around the World in the Wake of COVID-19 Epidemic of 2020, Seattle Pacific University, Seattle, WA. Refer to Appendix A.

ii The Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) created and produced Arts Performance Assessments (formerly Arts Classroom Based Performance Assessments [CBPAs]) beginning in 2003, to measure student achievement in Washington State, USA, in the arts (dance, music, theatre, and visual arts) via the artistic processes of creating, performing, presenting, and responding and in alignment with State arts learning standards for all learners, per state law. The summative performance assessments became formative performance assessments – with a design model that ensured success for all learners. They are on-line resources, free, and timeless. They remain in use today and are adaptable to all types of learning situations to measure individual student learning in and through the arts. A visual arts performance assessment example created during the pandemic is presented in this article in Appendix B1.