Summary: In this article we present the results of implementing an international project aimed at creating and developing inclusive education in various partner countries. The authors demonstrate how participation in the project allowed us to arrange a number of events and activities at the Vologda State University (Russia) and to develop an inclusive culture in the largest institution of higher education in the region. The paper describes the main stages and practices of project implementation. The authors also present the questionnaires for university students and staff that may determine the level of inclusive culture in educational institutions. The pilot survey showed that the designed questionnaires might be used to assess the inclusive culture in different universities.

Keywords: inclusive education, inclusive culture at universities, inclusive community, inclusive values, principles of inclusion.

Резюме: (Екатерина Тихомирова и Екатерина Шадрова: Формирование инклюзивной культуры вуза): В данной работе представлены результаты реализации международного проекта, направленного на создание и развитие инклюзивного образования в различных странах-участниках проекта. Авторы демонстрируют, как участие в проектной работе позволило осуществить комплекс мероприятий на базе Вологодского государственного университета (Россия) и сформировать инклюзивную культуру в крупнейшем вузе региона. Статья описывает основные этапы и формы работы с сотрудниками и студентами. Авторы также представляют разработанный инструментарий определения уровня сформированности инклюзивной культуры вуза, который может быть использован для оценки состояния инклюзивной культуры в высших учебных заведениях.

Ключевые слова: инклюзивное образование, инклюзивная культура вуза, инклюзивное сообщество, инклюзивные ценности, инклюзивные принципы

Zusammenfassung: (Ekaterina Tikhomirova & Ekaterina Shadrova: Formierung einer inklusiven Hochschulkultur): In dieser Arbeit werden die Ergebnisse eines internationalen Projekts vorgestellt, das auf die Schaffung und Entwicklung der inklusiven Bildung in verschiedenen Teilnehmerländern des Projekts gerichtet ist. Die Autorinnen zeigen, wie die Mitwirkung an der Projektarbeit es ermöglicht hat, einen Maßnahmenkomplex in der Staatlichen Universität Wologda (Russland) zu verwirklichen und eine inklusive Kultur in der größten Hochschule der Region zu entwickeln. Der Artikel beschreibt die Hauptstufen und –formen der Arbeit mit den MitarbeiterInnen und Studenten. Die Autorinnen stellen auch ein ausgearbeitetes Instrumentarium für die Bestimmung des Niveaus der Formierung einer inklusiven Hochschulkultur vor, das für die Bewertung des Zustandes der inklusiven Kultur an höheren Bildungseinrichtungen genutzt werden kann.

Schlüsselwörter: inklusive Bildung, inklusive Hochschulkultur, inklusive Gemeinschaft, inklusive Werte, inklusive Prinzipien

Problem description

Recently in the Russian Federation, as well as around the world, much attention has been paid to inclusive education, which often is considered as joint education of so-called “ordinary” learners and learners with disabilities. However, the development of contemporary society requires the term “inclusive education” to be defined more widely. In global educational practice, this concept is considered multidimensional. Besides, in the Russian Federation, in the federal law “On education in the Russian Federation” inclusive education is regarded as “the one ensuring equal access to education for all learners including those with special educational needs and individual differences” (Federal Law, 2012). Nevertheless, in Russian public opinion, special educational needs (SEN) and individual opportunities are often related to a single category of learners – those having mental and/or physical disabilities or medical problems, while there are other categories of learners, for example, gifted learners or culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) learners who also have special educational needs. This means inclusive education should deal with the educational community consisting of people of different nationalities, religions, cultures, social statuses, mental or physical abilities, different interests and so forth. It also means that any educational institution might be heterogeneous (or diverse) in its organisational structure.

In this regard in a society, first of all in various educational institutions, it becomes essential to create an inclusive culture based on the understanding of inclusive education as the possibility for different people to receive high-quality education at various levels based on their gender, nationality, language, physical, mental, social or other characteristics; for people who have various educational needs and opportunities but study together. Another important aspect of such an understanding of inclusive education is recognising diversity as a resource for further growth and improvement. A university, as one of the oldest forms of organising democratic relations in a certain community, especially in an academic one, can put such understanding of inclusion and inclusive culture into practice.

The importance of inclusive culture is shown in T. Booth and M. Ainscow’s (2011) Index for Inclusion, in which the authors present the indicators of inclusion in the form of a triangle, and place the dimension of “creating inclusive cultures” along the base of the triangle (p. 13). This means that the development of shared inclusive values and collaborative relations may lead to changes in other dimensions, namely “producing inclusive policies and evolving inclusive practices” (Booth & Ainscow, 2011, p. 13).

Therefore, inclusive culture, created at universities, influences the policy and practice of education, affects public opinion and act as a catalyst of positive changes towards diversity recognition; it becomes “an approach that sets out to transform education systems and other learning environments in order to address and respond to the diversity of all learners” (Mazurek & Winzer, 2015; [IDE-2015-2-full pdf, p. 87]).

The Concept of “inclusive culture at university”

According to N. Pless and T. Maak (2004), inclusive culture is “an organisational environment that allows people with multiple backgrounds, mindsets and ways of thinking to work effectively together and to perform to their highest potential in order to achieve organisational objectives based on sound principles” (Pless & Maak , 2004, p. 130). In our opinion, such a definition is generally applicable for any organisation irrespective of its main activity, and it does not reflect the character of specific educational institutions.

The concept “inclusive culture of higher education institutions (universities)” with the focus on diversity has also not been revealed in available academic publications and we developed our own definition which might be applicable not only to higher-education institutions but to any educational institution (primary or secondary schools, colleges, etc.). In our mind, inclusive culture at a university is a specific system of relations between all participants of an educational process (administration, teaching staff, learners, their parents, university community partners) which functions on the basis of inclusive values accepted by everyone and of the principles of inclusion allowing participant to interact effectively in a diverse environment in order to fulfill the mission of a university.

The creation of an inclusive culture in higher-education institutions enables the existence of a secure democratic community sharing the ideas of cooperation and the value of every person in the overall achievements. Such a university culture produces common inclusive values and principles that are shared by all employees and all students. In this inclusive culture, these values and principles influence the decisions concerning the university’s policy and daily educational practices. The development and improvement of higher education institutions becomes a continuous process.

The structure of inclusive culture in a university

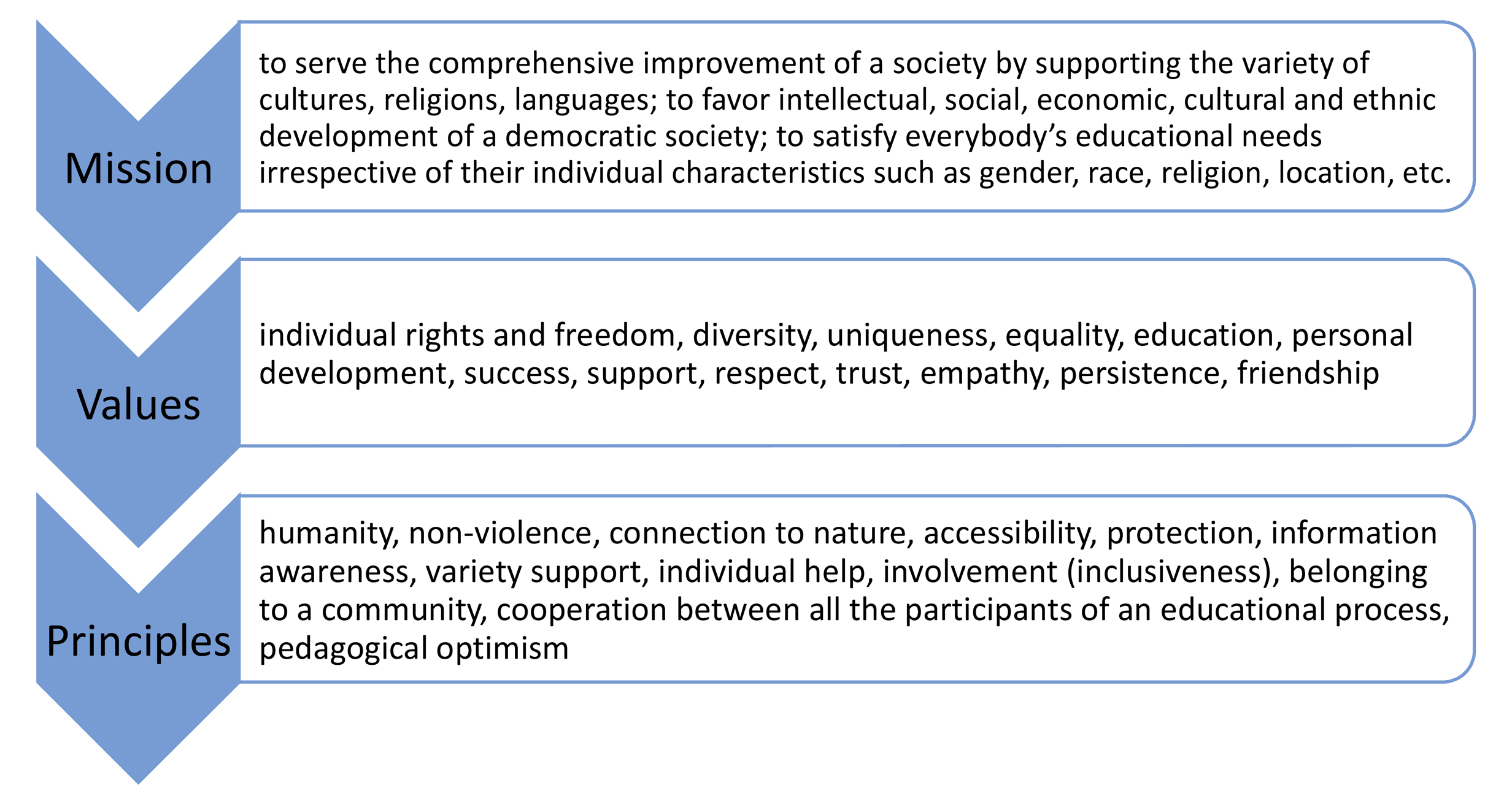

Based on our previous research (Tikhomirova & Shadrova, 2015a, 2015b) we developed a structure of inclusive culture of an educational institution. It includes the mission of an educational institution, its values, and principles underlying its activity (Fig.1).

The mission of an educational institution pertains to its purposeful directions underlying its activities, which have to be adhered to for a certain period of time. There are several traditional statements of a university mission that we do not deny such as: to satisfy the needs of citizens in high-quality professional education; to carry out scientific research; to develop future experts’ professionalism and their personal qualities including patriotism and humanism; to make information resources available for a wider community, etc. However, we would like to emphasize aspects of diversity while identifying the university’s mission. In this regard we believe that, apart from the above-mentioned statements, the mission of a modern higher-education institution should include the following: to serve the comprehensive improvement of a society by supporting a variety of cultures, religions, languages; to favor intellectual, social, economic, cultural and ethnic development of a democratic society; to satisfy everybody’s educational needs irrespective of their individual characteristics such as gender, race, religion, location, etc. The university mission is not limited to assisting the development of every learner’s personality, but by recognising these values of diversity it also disseminates the ideas of heterogeneity in a society.

The main values of higher education institutions as heterogeneous organizations are the following: individualism, individuals’ rights and freedom, diversity, uniqueness, equality, education, personal development, success, support, respect, trust, empathy, persistence, friendship. The presented system of values acts as a basis not only for the creation of inclusive culture in a higher education institution as a heterogeneous organization but also as an assessment tool for inclusive university activities since these values serve as a goalpost to define the degree of “inclusiveness” (involvement) of all participants in an educational process.

The main principles of inclusive culture, in our opinion, are the following: humanity, non-violence, connection to nature, accessibility, protection, information awareness, support for diversity, individual help, involvement (inclusiveness), belonging to a community, cooperation between all the participants of an educational process, pedagogical optimism.

In order to create inclusive culture at a university as a diverse organisation the following conditions should be met: 1) the mission of a higher-education institution and the values of inclusive culture should be realized and accepted by all the participants; 2) the values and principles of inclusive culture underlie the university’s activities and the relations of all the participants.

Creating an inclusive culture at Vologda State University

Having started in 2014 with the implementation of the TEMPUS project “Initial and Further Training for Teachers and Educational Managers with regard to Diversity” (543873-TEMPUS-1-2013-1-DE-TEMPUS-JPCR) as part of a consortium of 20 educational institutions from seven European countries, the Vologda State University project team faced several problems: 1) narrow understanding of the term “inclusive education” by university staff and students; they considered it the joint education of physically disabled people and people without disabilities; 2) superficial knowledge of principles and values of inclusive education; 3) lack of understanding of the importance of creating an inclusive university culture as a component of corporate culture; 4) absence of research tools to determine the existence or absence and the level of inclusive culture at university. We considered the first three problems as evidence of absence (or extremely low levels) of inclusive culture at the university and this influenced our primary objective, which is to create inclusive culture at the university as a component of its corporate culture. This objective was divided into smaller tasks: 1) to define the concept “inclusive culture of a higher-education institution” and its structure; 2) to raise university staff’s and students’ awareness of a broader interpretation of the concept “inclusive education”, the values and principles of inclusive culture, its role in the activities of a modern university; 3) to develop research tools to identify the level of inclusive culture in a higher-education institution; 4) to assess the level of inclusive culture at Vologda State University.

In order to implement the project at Vologda State University the Competence Center, aimed at providing psychological and pedagogical support to diverse groups of learners and educators, was opened on March 3, 2014. From this day until now the Competence Center has held meetings of project participants; meetings with university lecturers, school teachers and educational managers of the Vologda region; training seminars for educational managers and teachers; classes with bachelor, master and doctoral students; individual tutorials with learners studying the issues of inclusion within the TEMPUS project; individual counseling of students designing social projects within the TEMPUS project; assisting students with special educational needs. On average about 150 people, 80% of which are university students, work in the Competence Center weekly.

These are some of the most significant academic events held within the period of the project implementation:

- professional training courses on inclusion for university staff;

- workshops for university lecturers and school teachers on the methods and techniques of working with diverse groups of learners;

- lectures for master’s and postgraduate students (the following are some of the topics: “Taking individual learners’ aims into consideration in diverse educational groups”, “Multicultural interaction within an educational process”, etc.);

- roundtable sessions with invited guests and speakers from the regional educational authorities (“Inclusive education: urgent issues and future trends”, “Development of inclusive education in the region”, etc.);

- interactive classes for learners based on the principle “on equal terms” and other events.

Another important aspect of our work was devoted to the dissemination of the project results in the local community. Regular information messages about the events within the TEMPUS project were posted on the official university website (www.vstu.edu.ru), the official webpage of the Competence Center (www.vologda-uni.ru) and on the social-networking sites (Facebook, VK) in order to make them available for everyone. We also promoted the official TEMPUS-project website (www.tempus2013-16.novsu.ru). The survey of university staff and students conducted at the end of 2015 showed that 75% of lecturers and 100% of students consult this website as soon as they need information about inclusive education and issues of diversity, and 25% of lecturers visit it at least quarterly.

Thus, at our university we held several major events and organised a number of important meetings devoted to inclusive culture. As soon as these activities were finalized, we realized that we needed to monitor the changes that had happened at our institution. Therefore, we needed to design and test a tool that allows us to determine if and to what level an inclusive culture had been created.

Research methods to determine the level of inclusive culture at a university

In order to study inclusive culture at a higher-education institution two questionnaires were developed; one for university staff and the other for students (Appendices 1, 2). They were posted online on Google Forms. Each questionnaire contains 21 questions, some parts are the same in both questionnaires, while other parts differ due to the peculiarities of the groups of respondents. Questions are composed and adapted based on the developed structure of inclusive university culture and similar questionnaires offered by T. Booth & M. Ainscow (2011). The questionnaires contains two parts: one part with partly closed-ended questions which limit the answers of the respondents to response options provided; the other part consists of questions directed to identify facts, past or present actions, and also respondents’ opinions.

To study the process of creating an inclusive culture at a higher-education institution we allocated two units of questions devoted to 1) the creation of “inclusive community” and 2) the establishment of “inclusive values”. Each unit includes several indicators of inclusion.

The first unit reflects the following indicators:

- everyone feels welcomed at university (questions 1, 2);

- educational institution is open to others (questions 3, 4);

- there is mutual help and respect among students and staff (questions 5, 6, 7, 8);

- university staff cooperates (questions 9, 10);

- responsibility for the activities of a higher-education institution is shared (questions 11, 12);

- university community and external organizations work effectively together (questions 13, 14 and question 15 of the staff questionnaire).

The second unit reflects the following indicators:

- there are high expectations for all university students (question 15 of the student’s questionnaire, questions 16, 17);

- university staff, students, parents, local community, external organisations share the ideology of inclusion (questions 18, 19, 20 of the student questionnaire);

- recognition of inclusion as a resource for teaching and fostering everyone (question 20 of the staff questionnaire, question 21).

In order to identify the level of inclusive culture, it is necessary to calculate positive responses for each question (for example, responses “Yes”, “Always”, “Clearly”, “Mostly yes”). In questions 18, 19, 20 of the staff questionnaire and in questions 17, 18, 19, 20 of the student questionnaire the respondents’ choice of option “4 – fully agrees” is calculated as a positive answer. Other responses to the questionnaire questions, except positive ones, are used to reveal problem aspects in the inclusive university culture. Considering them while planning and monitoring activities will promote the development of inclusive culture in the future.

When analysing empirical data it is important to follow these steps:

- to define the percentage of respondents who answered positively in each question;

- to calculate a mean in each indicator;

- to calculate a mean in each of two units (creation of “inclusive community”, establishment of “inclusive values”);

- to calculate a mean of both units (all included data ).

The last figure will indicate the existence/absence of inclusive culture in a higher-education institution and in case of its existence, it will define its level. If a received result is less than 50, it indicates the absence of inclusive culture in an educational institution; if the result varies from 50 to 66, the level of inclusive culture is low; if it varies from 67 to 83, the level is average, from 84 to 100 it is high. The analysis of the results received at steps 2 and 3 will demonstrate the problems of “inclusiveness” at a higher-education institution and will help to plan actions for developing the university’s inclusive culture.

The offered method allows researchers and practitioners to carry out the analysis of empirical data by means of statistics. Thus, for example, it is possible to determine significant discrepancies comparing faculties or institutes, different university buildings, and categories of respondents.

Questionnaire testing and evaluation

Questionnaire testing was carried out in March, 2016 in the federal educational institution of higher education, “Vologda State University”. University staff and students from 12 faculties located in eight buildings of the university took part in piloting the questionnaires. The number of samples was determined as a minimum of 605 respondents, from whom students should constitute no less than 371 people and staff members – no less than 234 people (confidence probability at 95% and confidence interval (static error) +5%). In reality, the total number of respondents constituted 624 people (385 university students and 239 staff members, including 191 lecturers and 48 administrators).

The results, received during data analysis, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Inclusive culture indicators (Vologda state university, 2016)

| Indicators of university’s inclusive culture | All respondents (N=624), % | Students (N=385), % | All staff members (N=239), % | University administrators (N=48), % | University teaching staff (N=191), % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| everyone feels welcomed at university | 83.4 | 81.4 | 85.4 | 87.6 | 83.2 |

| educational institution is open to others | 75.9 | 81.8 | 70.1 | 76.9 | 63.3 |

| there is mutual help and respect among students and staff | 67.9 | 63.5 | 72.3 | 75.6 | 69.1 |

| university staff cooperates | 89.9 | 92.6 | 87.2 | 83.4 | 91.1 |

| responsibility for the activities of a higher education institution is shared | 74.7 | 82.7 | 66.7 | 66.8 | 66.7 |

| university community and external organizations work effectively together | 61.5 | 54.4 | 68.5 | 86.8 | 79.4 |

| Mean % in unit 1 | 75.5 | 76.0 | 75.0 | 79.5 | 75.4 |

| there are high expectations for all university students | 48.9 | 38.9 | 58.9 | 54.2 | 63.6 |

| university staff, students, parents, local community, external organisations share the ideology of inclusion | 71.0 | 67.6 | 74.4 | 74.0 | 74.9 |

| recognition of inclusion as a resource for teaching and fostering everyone | 78.2 | 87.9 | 68.5 | 70.3 | 66.7 |

| Mean % in unit 2 | 66.0 | 64.8 | 67.3 | 66.1 | 68.4 |

| Mean % (all indicators) | 70.8 | 70.4 | 71.1 | 72.8 | 71.9 |

The application of this research tool allowed us to determine the level of inclusive culture at Vologda State University as “average” (70.8%). In our case, this result means several positive shifts:

- the opinion of the university community on inclusion has changed towards understanding inclusion not only as inclusion of disabled learners in the university’s educational environment but as inclusion of everyone;

- the university has become open to everyone; it has become oriented to partnership relations with local community in inclusive educational practices;

- the university has become ready to promote students’ and lecturers’ success regardless of their nationality, religion, gender, health, social status, etc.;

- the majority of staff and students has recognized inclusion as a resource for further growth and development for both the university in general and any person in particular.

The data analysis also demonstrates that some indicators are expressed to a lesser degree. For example, the cooperation of our university with external organizations is not high (61.5%), which shows only indistinct links of our institution with other organizations. It might be possible that not all respondents are informed about university partners or, probably, they do not pay much attention to external contacts. Therefore, this inclusive-culture indicator might require clarification through extra tests or interviews.

Another inclusive-culture indicator that is less evident at our university is the expectation of high achievements from everyone (48.9%). On the one hand, it indicates the uncertainty in strong abilities of each learner while, on the other hand, it reveals the understanding that not all learners can achieve high results. The solution of this dilemma lies in the main idea of inclusion, that is the belief in each person’s potential. Accepting this idea by a university community will help to guide the personal achievements of everyone and will demonstrate the full recognition of inclusive values.

The revealed problem zones help to define what to start with while creating a university’s inclusive culture. In addition, the questionnaires reveal serious aspects of the university community’s opinion. These aspects are not widely analyzed in this article, but they can also be used when determining a state of inclusive culture at a higher-education institution.

Conclusions

During the 2.5 years of the TEMPUS-project implementation at the Vologda State University a number of academic, educational and organisational activities aimed at creating an inclusive culture have been carried out successfully. As a result, based on the developed questionnaires for students and instructors the level of the university’s inclusive culture has been identified as average. It provided evidence of the effectiveness of the work conducted during project implementation; but it also indicated the need to continue because the process of developing an inclusive culture at a higher-education institution is a long-term and persistent one. The university’s inclusive culture is characterized by the integration of all its components; it might be considered as a system whose creation and development are influenced by both internal (university) and external (regional, national, international) factors. Eventually, influenced by these factors, the inclusive culture at a higher-education institution may change; it means that it is not stagnant but changeable and dynamic: the mission of the university may be modified; the values and principles may become outdated and take on new meanings, even new values and principles may appear, etc. At the same time the inclusive culture of a higher-education institution is limited to a certain framework which includes only what corresponds to its values. Another important peculiarity of inclusive culture is that it can educate a new member of a university community so that this person may recognise and accept it; and what is more, inclusive culture might be transferred to other educational institutions.

The developed questionnaires make it possible to assess the existence/absence and level of inclusive culture at a higher-education institution. Key indicators are grouped in two units which enable the diagnosis of the creation of “inclusive community” and the establishment of “inclusive values”. The provided questionnaires for university staff and students may be applied at different stages of projects aimed at developing inclusive education: while creating inclusive culture, as well as while monitoring its formation at a higher-education institution. The qualitative analysis of responses helps to reveal “strong” and “weak” points in inclusive culture and on this basis to plan actions to correct them.

In addition, defining the level of inclusive culture at higher-education institutions enable the implementation of further inclusive policies and inclusive practices. The higher the level of inclusive culture is, the more effective is the process of promoting and developing the ideas of inclusion and diversity. There is no doubt this process will also require identifying accurate criteria and indicators in order to be implemented successfully. The research tools we offer might form the basis for creating new methods and techniques and can be applied in various organizations.

References

- Booth, T. & Ainscow, M. (2011): Index for Inclusion: developing learning and participation in schools. Bristol: Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education (CSIE).

- Mazurek, K. & Winzer, M. (2015): Intersections of Education for All and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: Explaining the Conflicting International Cadences of Inclusive Schooling. In: International Dialogues on Education: Past and Present (IDE-Online Journal). URL: www.ide-journal.org/journal/?issue=2015-volume-2-number-2; IDE-2015-2-full.pdf, pp. 85-93 (retrieved: August 10, 2016).

- Pless, N. & Maak, T. (2004): Building an Inclusive Diversity Culture: Principles, Processes and Practice. In: Journal of Business Ethics, October. pp. 129-147.

- Тихомирова, Е.Л. & Шадрова, Е.В. (2015a) [Tikhomirova E. & Shadrova E.]: Ценности инклюзивной культуры школы как гетерогенной организации [Values of inclusive culture of school as a heterogeneous organisation]. In: Вестник Костромского государственного университета [Kostroma State University Herald], Nr. 4 (21), pp. 10-15.

- Тихомирова, Е.Л. & Шадрова, Е.В. (2015b) [Tikhomirova E., Shadrova E.]: Принципы инклюзивной культуры школы как гетерогенной организации [Principles of inclusive culture of school as a heterogeneous organisation] In: Педагогика и психология как ресурс развития современного общества: Проблемы сетевого взаимодействия в инклюзивном образовании [Pedagogy and Psychology as a resource for a contemporary society development: Issues of Networking in Inclusive Education]. Рязанский государственный университет, pp. 78-83.

- Федеральный закон от 29.12.2012, № 273-ФЗ «Об образовании в Российской Федерации» [Federal Law on “Education in the Russian Federation”, 29.12.2013, № 273-FL]. URL:http://consultant.ru/document/cons_doc_law_140174. (retrieved: May 21, 2016).

Appendix 1: Questionnaire for university staff

Dear colleagues!

Our university participates in an international project aimed at developing inclusive education. Our university authorities invite you to take part in an anonymous online survey. We need to know everyone’s opinion in order to analyse the results properly. We kindly ask you to answer honestly and without any consultations. Please, read the questions and the options carefully. Choose the answer that is the closest to your opinion and mark it. You need to answer all the given questions. We thank you in advance.

Your position at university: administrative staff teaching staff

Indicate you faculty if relevant:

1. Are people at university welcoming and friendly to you when you come to work there?

Yes

No

Other:

2. Is the university welcoming to all students including students with impairments, refugees and asylum seekers?

Yes

No

Other:

3. Is university information made accessible to all, for example by being translated, Brailled, audio recorded, or in large print when necessary?

Yes

No

Other:

4. How clearly the documents, notices and displays demonstrate that the university welcomes people with different identities and/or coming from various cultures?

Clearly

Not quite clearly

Other:

5. Do students seek help from and offer help to each other when it is needed?

Mostly yes

Rarely

Mostly not

Other:

6. How often do displays celebrate collaborative work by students as well as individual achievements?

Always

Sometimes

Never

7. How often do students report to a member of university staff when they or someone else needs assistance?

Always

Sometimes

Never

8. Do students avoid racist, sexist, homophobic, disablist, and other forms of discriminatory name-calling?

Always

Sometimes

Never

9. Do university staff treat each other with respect irrespective of their positions and roles at university?

Always yes

Mostly yes

Mostly not

No, never

10. Do university staff treat each other with respect irrespective of their class and ethnic background?

Always yes

Mostly yes

Mostly not

No, never

11. Are all staff involved in drawing up priorities for university development?

Yes, all of them

Only university authorities

Other:

12. Do you feel ownership of the university development plan?

Yes, certainly

Not always

No

13. Does the university involve local communities, such as elderly people and the variety of ethnic groups, in university activities?

Yes, always

Sometimes

Rarely

Other:

14. Do university staff and trustees study what local community think about them?

Yes, it is obligatory

Sometimes

No

Other:

15. Do the views of members of local communities affect university policies?

No, university policies are determined by different factors

Yes, if these views are significant

Always yes

Other:

16. Do you treat all university students as if their highest achievements are not limited?

Always yes

Not all students

Very rarely

Other:

17. Do you avoid viewing students as having a fixed ability based on their current achievements?

Always yes

Sometimes

No, almost never

18. To what extent do you appreciate diversity compared to ‘normality’?

not fully ① ② ③ ④ fully

19. To what extent do you agree that inclusion is not only about access to university but also about increasing participation in it?

not fully ① ② ③ ④ fully

20. Do you agree that the university educational environment includes learners and staff relationships, buildings’ accessibility, cultures, policies, curricula and teaching approaches?

don’t agree ① ② ③ ④ fully agree

21. Do you think that categorizing learners as “having special educational needs” can lead to their devaluation and separation?

Yes

I am not sure

No

Other:

Thank you for your answers and participation

Appendix 2: Questionnaire for university students

Dear students!

Our university participates in an international project aimed at developing inclusive education. Our university authorities invite you to take part in an anonymous online survey. We need to know every student’s opinion in order to analyse the results properly. We kindly ask you to answer honestly and without any consultations. Please, read the questions and the options carefully. Choose the answer that is the closest to your opinion and mark it. You need to answer all the given questions. We thank you in advance.

Your faculty (major):

1. Were people at university welcoming and friendly to you when you came to study there?

Yes

No

Other:

2. Is the university welcoming to all students including students with impairments, refugees and asylum seekers?

Yes

No

Other:

3. Is university information made accessible to you and your parents, for example, by being translated, Brailled, audio recorded, or in large print when necessary?

Yes

No

Other:

4. How clearly the documents, notices and displays demonstrate that the university welcomes people with different identities and/or coming from various cultures?

Clearly

Not quite clearly

Other:

5. Do you seek help from and offer help to other students when it is needed?

Mostly yes

Rarely

Mostly not

Other:

6. How often do displays celebrate students’ collaborative work as well as your individual achievements?

Always

Sometimes

Never

7. How often do you ask a member of university staff for help when you or other students need assistance?

Always

Sometimes

Never

8. Do you avoid racist, sexist, homophobic, disablist, and other forms of discriminatory name-calling?

Always

Sometimes

Never

9. In your opinion, do university staff treat each other with respect irrespective of their positions and roles at university?

Always yes

Mostly yes

Mostly not

No, never

10. In your opinion, do university staff treat each other with respect irrespective of their class and ethnic background?

Always yes

Mostly yes

Mostly not

No, never

11. Do you think that all staff are involved in drawing up priorities for university development?

Yes, all of them

Maybe, not all of them

I am sure that not all of them are involved

12. Do you think that students’ opinion influences the university development plan?

Yes, certainly

Mostly yes

Not always

I am sure not

13. Does the university involve local communities, such as elderly people and the variety of ethnic groups, in university activities?

Yes, always

Sometimes

Rarely

Other:

14. In your opinion, do the views of members of local communities affect university policies?

No, university policies are determined by different factors

Yes, if these views are significant

Always yes

Other:

15. Do you think that you study at university where your highest achievements are not limited?

Yes

I don’t think so but there are some who would agree

I am sure not

Other:

16. Do lecturers avoid negative attitude to university students who are not having high achievements?

Always yes

Sometimes

No, almost never

17. Are you or other students supported if sometimes you feel bad or stressed?

not fully ① ② ③ ④ fully

18. To what extent do you agree that inclusion is not only about access to university but also about increasing participation in it?

not fully ① ② ③ ④ fully

19. To what extent do you agree that all cultures and religions encompass a range of views and degrees of observance?

not fully ① ② ③ ④ fully

20. To what extent do you avoid gender stereotyping in expectations about achievement, students futures or in help with tasks, such as refreshments or technical support?

not fully ① ② ③ ④ fully

21. Do you think that categorizing students as “having special educational needs” can lead to their devaluation and separation?

Yes

I am not sure

No

Other:

Thank you for your answers and participation

About the Authors

Dr. Ekaterina Tikhomirova: PhD in Pedagogy, associate professor, Dean of the Faculty of Social Work, Pedagogy and Psychology, Vologda State University, Vologda (Russia). Contact: ekaterinatichomirova@yandex.ru

Dr. Ekaterina Shadrova: PhD in Pedagogy, associate professor, Department of English, Vologda State University, Vologda (Russia). Contact: ekaterina-shadrova@yandex.ru